HUGE B-29 RAID DESTROYS JAPANESE CAPITAL

Tokyo, Japan • March 9, 1945

Apart from Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle’s April 1942 raid on the Japanese capital, Tokyo, early air raids on Japan focused on military and industrial targets with disappointing results. So, U.S. Army Air Forces Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay, a veteran of the Eighth Air Forces’ horrific air campaign over Nazi Germany, filled each of his new silver-skinned, 4‑engine Boeing B‑29 Superfortresses with 10 times the payload carried by Doolittle’s twin‑engine B‑25 Mitchells. With highly effective incendiary bombs in their bomb bays, 297 B‑29s of the XXI Bomber Command, a unit of the Twentieth Air Force, flying at only 230 mph/370 km/h and at staggered altitudes between 4,900 and 9,200 ft/1,483 and 2,804 m, firebombed Tokyo late on this date, March 9, 1945, and into the early morning hours of March 10 in an operation called “Meetinghouse,” code for the urban area of the Japanese capital. The largest B‑29 formation to date, it was so big that it took 3 hours for all the warbirds to become airborne.

Weather conditions over Tokyo were good that night, and the low-flying B‑29 pathfinders had no difficulty marking their targets with napalm-filled bombs designed to cause fires to attract the attention of Japanese firefighters. The lead formations dropped their bombs at 100 ft/30 m intervals, but the main force, delivering M‑69 incendiaries, dropped their payloads at half the distance for better concentration. An increasing wind fanned the flames of the fires caused by the napalm and incendiaries, producing an expanding firestorm. As the fires spread, bombardiers dropped their bombs on the fiery edges, thus increasing the size of the conflagration. The fires that spread throughout the capital were only hampered by wide firebreaks, particularly along rivers and canals. Although thousands of people managed to save themselves by jumping into city waterways, the heat was so intense that water in some of the shallower canals literally boiled them to death.

The Dante-esque raids on a densely populated area of 16 sq. miles/41 sq. kilometers proved the single-most destructive bombing raid in history, overwhelming the city’s fire-fighting and other emergency services inside 2 hours: 267,000 buildings and homes (many built of wood and paper) were destroyed and an estimated 100,000 Tokyo residents were killed in the target area. Given that the death toll may be understated, Operation Meetinghouse certainly inflicted the highest loss of life of any aerial bombardment of the war, including victims of Hamburg (42,600) (Operation Gomorrah), Berlin (20,000–50,000), Dresden (25,000), Hiroshima (70,000–80,000), or Nagasaki (40,000–75,000). Japan’s aircraft manufacturing center, Nagoya, suffered the night after the Tokyo raid and again a week later. In between it was Osaka’s and Kobe’s turn.

After “Blitz Week” (a total of 1,434 sorties on the main Japanese island of Honshū), Tokyo was again razed on May 23 and 25, leaving 3 million urbanites now homeless, followed on May 29 by Yokohama’s business district and waterfront (one-third of the city). In May alone one-seventh of Japan’s built-up urban area—a staggering 94 sq. miles/243 sq. kilometers —had been devastated, raising total urban destruction to over one-third.

LeMay described his B‑29 campaign as “Bomb and burn ’em until they quit.” (LeMay’s predecessor at XXI Bomber Command, Brig. Gen. Haywood S. Hansell, Jr., balked at dropping incendiaries on Japan, which he viewed as both morally repugnant and militarily unnecessary.) Along with ineffective Japanese intercept aircraft, LeMay’s campaign dramatically limited Japan’s options to avoid murderous annihilation. Because of the terrifying attacks on Tokyo (over 50 percent of the city’s urban area had been reduced to ashes), the Japanese capital was spared further fire raids because it was no longer a viable target. One B‑29 flier quipped, “Tokyo just isn’t what it used to be.”

Saturation Bombing, Tokyo, 1944–1945

|  |

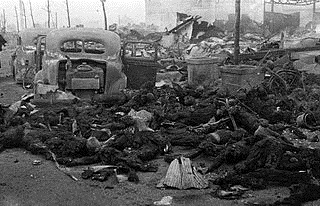

Left: The charred remains of civilians after the carnage and destruction wrought by 1,665 tons of bombs falling on Tokyo the night of March 9/10, 1945. Radio Tokyo called the attack “slaughter bombing.” The majority of the bombs were 500‑lb/227‑kg cluster bombs packed with napalm-carrying incendiary bomblets. The intent of LeMay’s Operation Meetinghouse had been to produce “the greatest psychological effect” on Japanese civilians and leaders, and one leader in particular. Emperor Hirohito’s tour of the destroyed areas of his capital on March 18 is often thought to have been the beginning of his personal involvement in the peace-making process.

![]()

Right: A virtually destroyed Tokyo residential section following saturation bombing. With wartime peak levels as high as 135,000 persons per square mile, Tokyo had the highest density of any industrial city in the world. An estimated 1.5 million people lived in the city wards devastated by Operation Meetinghouse. By the end of World War II over 50 percent of Tokyo had been reduced to ashes. In fact, an estimated 40 percent of Japan’s built-up cities were destroyed in U.S. air attacks in 1944–1945.

|  |

Left: Boeing built 3,970 of these 4-engine, propeller-driven bombers between 1943 and 1946. Though designed as a high-altitude daytime bomber, in practice B‑29s actually flew more low-altitude nighttime incendiary bombing missions. B‑29s carried out the atomic bombings that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, respectively. On August 14, 1945, the last day of combat in World War II, B‑29s targeted the Japanese naval arsenal at Hikari on the southern tip of Japan’s main island, Honshū.

![]()

Right: Tokyo burns under a B‑29 firebomb assault, May 26, 1945. B‑29 raids on Tokyo began on November 24, 1944, and lasted until August 15, 1945, the day Japan capitulated. Twin-engine bombers and fighter-bombers carried out additional attacks on Tokyo. The last desperate air combat of the Pacific War occurred on August 18, when 2 Consolidated B‑32 Dominators on a “routine” photoreconnaissance mission in the vicinity of Tokyo were attacked by 17 renegade Japanese fighter planes. The photo recon mission proved that some Japanese aircraft were noncompliant with ceasefire terms that required Japanese aircraft to remain on the ground. Sgt. Anthony Marchione, a 21‑year-old gunner/photographer’s assistant, on board Hobo Queen II, one of the B‑32s (a 4‑engine heavy bomber, less well-known rival to the B‑29), was the last American to die in air combat in World War II.

March 1945 “Blitz Week” Targets: Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe (Four Consecutive Videos)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click