HOLOCAUST AND GERMAN BUSINESSES JOINED AT HIP

Auschwitz, German-Occupied Poland • June 14, 1940

On this date in German-occupied Poland 728 male political prisoners, Catholic priests, and Jews left Tarnów’s train station for Auschwitz concentration camp (Konzentrationslager Auschwitz), 80 miles/129 kilometers away. It was the first mass transport of prisoners to Auschwitz (Polish name, Oświęcim) since the camp was opened for business on April 27, 1940, by order of Reichsfuehrer-SS Heinrich Himmler. Run by Himmler’s paramilitary Schutzstaffel SS-Totenkopf Division (SS Death’s Head Division), the Auschwitz Stammlager (main camp) in March 1941 held 10,900 inmates, most of them Poles. Not until sometime in February 1942, but most definitely by spring of that year when the first 3 ovens in Crematorium I became operational, did freight trains begin delivering Jewish families from all over German-occupied Europe to what became known as Auschwitz I. In July 1942 mass killings shifted to a second, soon to be largest Auschwitz facility, Birkenau (Auschwitz II), where eventually 4 crematoria came online. Several months earlier, in March 1942, construction got underway on a third camp slightly over 6 miles/9 kilometers from Auschwitz I—this at Auschwitz III-Monowitz after the Reich Ministry of Economy (Reichswirtschaftsministerium) started offering tax exemptions to corporations that were willing to develop industrial enterprises on the Reich’s eastern frontier.

One of the first corporations to embrace the government offer was IG Farbenindustrie AG, an affiliated group of chemical and pharmaceutical manufacturers (BASF, Bayer, Hoechst, et al.). Among several sites IG Farben considered in December 1940–January 1941 was the area between Oświęcim and the Polish villages of Dwory and Monowice (German, Monowitz) in Upper Silesia. This was territory that Germany had annexed shortly after the country had invaded Poland, the act that ignited World War II in Europe. The decision of IG Farben’s board of directors was justified by the area’s favorable geological conditions (the availability of raw materials like coal, limestone, and salt), plentiful water supply, and access to railroad lines. The near-certainty of employing prisoners as cheap labor from the Auschwitz Stammlager was likely decisive in choosing the plant site. Plus, the site was practically a steal in that it was seized without compensating their owners. Vacated homes not demolished in clearing the campus were sold to the company as housing for employees or set aside for members of the SS garrison. IG Farben executive board member Otto Ambros, the firm’s expert on both Buna (IG Farben’s brand name for synthetic rubber) and poison gas (brand name Zyklon B made by an IG Farben subsidiary), was delighted with the easy working relationship between company and Auschwitz authorities: “Our new friendship with the SS is very fruitful.”

In late October 1942 IG Farben’s company-owned forced labor camp opened on plant grounds on the site of the former Polish village of Monowice. The first 2,100 SS prisoners arrived in October and November from Buchenwald, Sachsenhausen, and Dachau concentration camps, as well as from camps in the Netherlands. Over the next 27 or so months, IG Farben requisitioned thousands upon thousands of voluntary (mainly foreign) and forced laborers (compelled against their will) and slave laborers from Reich labor deployment authorities as well as from the pool of prison inmates at Auschwitz I. Most laborers consigned to Auschwitz III-Monowitz (aka Buna-Monowitz), around 25,000 to 30,000, succumbed to the effects of over-crowded housing, inadequate clothing (especially in winter) and food (both necessities supplied by the SS except for a hot, watery “Buna soup” at noon), disease, ill-treatment, exhaustion, and 56‑hour work weeks. Or they were shot at the Buna-Werke construction site or hanged at the labor camp. Over 10,000 fell victim to camp “selections,” killed by a lethal injection of phenol to the heart in the camp hospital or dispatched to Auschwitz II-Birkenau’s Zyklon B gas chambers. In late 1944, on the eve of the Auschwitz complex’s liberation by Soviet soldiers, more than 10,000 workers, primarily Jews, were incarcerated by IG Farben at Auschwitz III-Monowitz.

Life in the Shadow of Extermination: IG Farben at Auschwitz III-Monowitz, 1942–1945

|  |

Left: Walking the construction site of IG Farben’s Buna-Werke (Buna Works) synthetic rubber and liquid fuel plant is Reichsfuehrer‑SS Heinrich Himmler (first row, middle), flanked on his right by Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Hoess (pronounced “hearse”) and on his left, in civilian clothes, by IG Farben engineer Maximilian Faust, on-site representative for plant manager Otto Ambros. Photo taken July 18, 1942, on the second day of Himmler’s visit. Faust personally explained to Himmler the progress of construction and what the plant’s principal deliverables to the Wehrmacht were: Buna (synthetic) rubber of course, poison gas, and explosives. Sharing the Auschwitz-Monowitz location were over 40 firms. For example, the electrical engineering company Siemens-Schuckert had a slave labor camp known as Bobrek concentration camp near its factory. Bobrek held approximately 250–300 prisoners, among them 50 women, who produced electrical parts for aircraft and U‑boats. Krupp, the giant West German armaments maker, built an automatic weapons parts plant near Monowitz with the intention of using 550–600 Auschwitz inmates as laborers to manufacture shell casings and to supply fuses, anti-aircraft cannons, and howitzers to the Wehrmacht. The SS obligingly relocated 500 skilled Jewish workers to Auschwitz for Krupp’s proposed fuse-production facility.

![]()

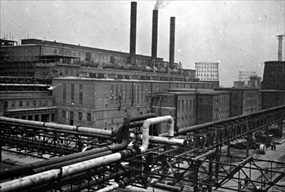

Right: IG Farben’s industrial complex at Auschwitz III-Monowitz was slated to become the biggest chemical plant in Eastern Europe. The engineering and production facilities were planned so that they could produce synthetic rubber and motor fuels in peacetime. Residential barracks grouped into 10 lager (camps) were located across the road from the fenced-in Buna-Werke plant. Workers were escorted to and from the plant by SS guards. Those not amenable to SS-type discipline at the factory-owned labor camp or the Buna-Werke plant, where they were overseen by IG Farben police, supervisors, and 200‑plus construction contractors, were sent back to the main Auschwitz concentration camp or, as was more often the case, to Birkenau for extermination. To the Wehrmacht’s misfortune, in the same month, January 1945, the Buna-Werke plant was completed, it was overrun by units of the Red Army (January 27, 1945). Buna-Werke was never able to deliver its primary product—synthetic rubber.

|  |

Left: The great mass of IG Farben labor was simply unfree. If workers attempted to leave or escape their place of employment—even those acquired by way of temporary manpower services, recruitment by third-party firms, or individual recruitment—they were subject to arrest and internment by Himmler’s SS Sicherheitspolizei (security police, or “SiPo”) in Germany, their home countries, or German-occupied territories. Among the foreign workers (Fremdarbeiter), only the Poles were explicitly labeled forced laborers (Zwangsarbeiter). This was an arbitrary usage, because many factories made use of over 3 million “Ostarbeiter” (“Eastern workers”), most of whom were young people drafted by force in occupied territories of the Soviet Union, as we see in this 1941 photo of a female Ukrainian lathe operator at the IG Farben plant in Auschwitz III-Monowitz. Separate IG Farben barracks were maintained for Germans drafted for “service duty” and for each of the even less free categories of drafted foreign workers (e.g., males ensnared by Vichy France’s Service du travail obligatoire, or STO), prisoners of war, and Eastern European forced laborers, as well as for forced laborers taken from the SS concentration camp system. By February 1943 IG Farben’s sprawling residential camp system of 10 lager (e.g., one for Jews, one for German civilians, one for forced laborers from the Soviet Union, one for young male apprentices, one for girls from the Bund Deutscher Maedels) had been expanded to hold 108,593 places for 70,543 Fremdarbeiter, 19,958 Germans, 14,156 POWs, 2,195 German military prisoners, and 1,741 other workers.

![]()

Right: A roadworks crew of forced laborers, probably at Auschwitz III-Monowitz, worked a 56‑hour work week as did other kinds of IG Farben workers. The odds of surviving employment at IG Farben’s plants and subsidiaries varied, but overall about one-third of all forced laborers used by the concern did not survive. One estimate is that between 23,000 and 25,000 prisoners were either killed by the authorities or died from hunger, disease, or exhaustion at the Auschwitz III-Monowitz labor camp, the Buna-Werke construction site, and outlying mines. (Life expectancy for mine workers was 1 month.) The total number of dead at IG Farben’s approximately 100 construction and production sites in Germany and German-occupied Europe ranges from 31,500 to 33,500, with the high point in fall 1944.

Auschwitz III-Monowitz and IG Farben, a Film Narrated by Dr. Tomasz Cebulski, August 2020

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click