HITLER’S STURMABTEILUNG FORMALLY DEBUTS

Munich, Germany • October 5, 1921

On this date in 1921 the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartie, NSDAP or Nazi Party) headed by Adolf Hitler formally established the Sturmabteilung (lit. “Storm Detachment”). The organization is better known by its initials SA and colloquially as “brownshirts” (Braunhemden) for the color of their shirt uniform. The SA’s several antecedents are found in German World War I specialized assault troops and later, after the Nazi Party was formed in Munich in January 1919 under the name German Workers’ Party, in the “Gymnastic and Sports Division” (Turn- und Sportabteilung), a disarming cover name for the stormtroopers, as they have also been called. Comprised of ex-soldiers, beer-hall hooligans, and “disheveled rabble” (Hitler’s words), the function of the future SA was to protect Nazi Party gatherings from disruptions involving followers of other political parties, notably the Social Democrats (SPD) and Communists (KPD). A mêlée in downtown Munich’s Hofbraeuhaus on November 4, 1921, when Hitler spoke to a large mixed crowd, solidified the notoriety of the party’s militant wing for brawling with anyone and everyone viewed as an opponent of the party and its vision of German Volksgemeinschaft (national or ethnic community). (See yellow text box below.)

In the Depression Era of the late 1920s/early 1930s, as the Nazis grew from an extremist fringe group to the largest political party in Germany, Hitler assumed supreme command of the SA as its new Oberster SA-Fuehrer. He invited Ernst Roehm, an early Hitler ally and an SA co-founder, to serve as SA Stabschef (chief of staff). Between 1931 and 1933 SA membership exploded to over 2 million men compared with the tiny Reichswehr (Germany Army), which was limited by law to 100,000 men at arms. Reichswehr brass, with their old-school Prussian traditions, did not look kindly on a powerful rival organization, a new “people’s army” over which they had no influence. The SA appeared to threaten the Reichwehr’s existential role as Germany’s true national defense force by absorbing it into their ranks of untrained thugs.

Hitler, Germany’s new chancellor since January 30, 1933, had his own concerns with the SA. So too did Nazi Party bigwigs Hermann Goering and Heinrich Himmler, the latter heading up the Schutzstaffel (SS), the Nazi Party’s elite “Protection Squadron.” The trio saw Roehm as a rival center of power, a man conspiring to use his stormtroopers to unseat Hitler. Already noted were senior Reichswehr officers who worried about their fate. Then there were the German industrialists and financial magnates who had supplied much of the wherewithal for the Nazis’ electoral gains in the Reichstag (German parliament) and in the Laender (states). This group worried over Roehm’s socialistic views on the economy and his claims that the real revolution was still to come.

Hitler’s cynical betrayal of Roehm and the SA became known as “The Night of the Long Knives” (Nacht der langen Messer). The decapitation of the SA leadership began on June 30, 1934. Roehm and other influential SA officials were eliminated by Himmler’s SS (Roehm was shot dead in his holding cell when he refused to commit suicide) as were other figures thought to be in cahoots with Roehm. Hitler justified the murder of as many as 100 of his opponents and the arrest of over a thousand “mutineers” in a 2-hour speech on July 13 to the Reichstag, now short 13 members who had been killed in the “Roehm Putsch.”

The failing 86-year-old German president Paul von Hindenburg was given a telegram drafted by Nazi Party members, which he dutifully forwarded to Hitler, congratulating the chancellor on having “nipped treason in the bud” and saving “the German nation from serious danger.” Upon Hindenburg’s death on August 2, 1934, Hitler’s cabinet appointed their leader Fuehrer und Reichskanzler, a merger of offices confirmed in a national plebiscite (89.9 percent voting in favor) on August 19, 1934.

Rise and Fall of Sturmabteilung (SA) Chief Ernst Roehm (1887–1934)

|  |

Left: Although the German public did not complain much when SA activities were directed against Jews, communists, and socialists, by 1934 there was general concern about the level of civic violence for which Roehm’s stormtroopers were responsible. President Hindenburg went so far as to inform Hitler in June 1934 that if the chancellor did not to curb the excesses of his SA, he would dissolve the government and declare martial law. This photo shows Roehm’s (and by extension, Hitler’s) thuggish workforce in front of a Jewish shop during the boycott of Jewish businesses in Germany on April 1, 1933. The sign says: “Germans, Attention! This shop is owned by Jews. Jews damage the German economy and pay their German employees starvation wages. The principal owner is the Jew Nathan Schmidt.”

![]()

Right: Hitler posing in Nuremberg’s Main Market Square, 14th-century brick Gothic Frauenkirche (“Church of Our Lady”) as a backdrop, with SA members during the Fourth Nazi Party Congress, August 1–4, 1929. In the foreground, bedecked as usual in medals, is Hermann Goering. Goering, together with Reich Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda Joseph Goebbels and Schutzstaffel (SS) head Heinrich Himmler, plotted the demise of the SA. Goering personally reviewed the list of detainees who were to be killed in the “Night of the Long Knives.”

|  |

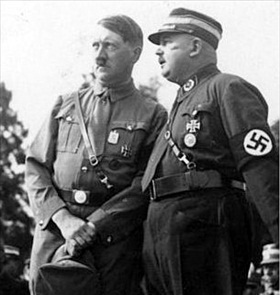

Left: Mustered out of the Kaiser’s army as a captain, Ernst Roehm continued his military career as an adjutant in the Reichswehr, the much diminished defense force of the Weimar Republic (1919–1935). In 1919 he joined what became the Nazi Party and he and Hitler became close friends. He was tried along with Hitler for participation in the November 1923 Munich Beer Hall Putsch. From his prison cell in Landsberg, Bavaria, Hitler gave Roehm permission to rebuild the Sturmabteilung any way he saw fit. Under both men the SA grew to number nearly 3 million men who engaged in street battles with communists and Jews. Hitler is pictured with SA Chief of Staff Roehm at the 1933 Nuremberg Party Rally.

![]()

Right: Hitler triumphant. Chastened SA troops parade past Hitler during the 1935 Nuremberg Party Rally. Hitler admitted in a speech to the Reichstag on July 13, 1934, that the killings connected with the “Night of the Long Knives” had been illegal but claimed a plot had been underway to overthrow the government. (For his Reichstag speech Hitler ordered the German secret police (Gestapo) to produce an “official” casualty list: 61 shot dead, 13 allegedly died resisting arrest, and 3 suicides.) A tame Reichstag passed a measure that retroactively made the action legal.

Adolf Hitler, Ernst Roehm, and the Night of the Long Knives

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click