HITLER, WIFE CREMATED AFTER SUICIDES

Berlin, Germany • April 30, 1945

Sometime after 3 p.m. on this date in 1945 Adolf Hitler, to all the world the face of unspeakable evil, shot himself in the right temple after he and Eva Braun, his wife of 40 hours (and near-secret mistress for 14 years), had poisoned themselves by ingesting cyanide. The Fuehrer’s psychotic desire for an apocalyptic end for Germany—a Nazi Goetterdaemmerung reminiscent of composer Richard Wagner’s “Twilight of the Gods”—was nearly completed by his death, leaving Berlin’s formal surrender in the hands of its garrison commander, Gen. Helmuth Weidling, 2 days later.

From the recessed Fuehrerbunker, Hitler’s pall bearers carried the bodies of Eva Braun and their troglodyte leader into the once-beautiful, now desolated gardens of the ruined Old Reich Chancellery. The pall bearers (and former wedding attendants) were Erich Kempka, Hitler’s chauffeur since 1932; Heinz Linge, Hitler’s valet for the last 10 years; Martin Bormann, ruthless head of the Reich Chancellery and executor of Hitler’s estate; Joseph Goebbels, ueber-loyal apostle, Hitler diarist, bombastic Minister of Propaganda, and recently appointed German Chancellor; and Dr. Ludwig Stumpfegger, disgraced Reichsfuehrer‑SS Heinrich Himmler’s former personal physician (now Hitler’s) and the provider of the poison capsules. Hitler’s personal adjutant, Otto Guensche, carried the body of Eva Braun who was wearing a black dress with roses around the neckline, Hitler’s favorite. The 2 corpses were laid next to each other just yards/meters from the bunker exit, Hitler on his back clad in his customary uniform tunic, white shirt, and black trousers, and his wife on her stomach.

Shortly before 4:00 o’clock that afternoon 10 canisters of gasoline were poured over the couple’s remains and set on fire. Hitler had chosen cremation for himself and his wife, telling his Minister of Armaments, Albert Speer (pronounced “spare”), that he would “not fight personally. . . There is always the danger that I would just be wounded and fall into the hands of the Russians alive. I don’t want my enemies to disgrace my body either.” Actually, the Soviets did hope to catch Hitler alive, going so far as to set up a special unit to do just that. Marshal Georgy Zhukov, who signed the second German military surrender on May 8/9, 1945, in Berlin for the Soviet Union, boasted that if he caught “that slimy beast Hitler” he would lock him in a cage and parade him through the streets of Moscow, probably on June 24, when the marshal served as commander in chief of the Moscow Victory Parade. Cheated of that honor, Zhukov was unaware on the evening of April 30 that the piles of bones and ash, the latter kicked up by winds blowing through in the barren Chancellery garden, belonged to Hitler and Braun.

In his last will and political testament, Hitler stated for the public record that he and his wife chose death rather than witness the overthrow and capitulation of his nation. “I die with a happy heart,” he wrote, “conscious of the immeasurable deeds and achievements of our soldiers at the front, of our women at home, the achievements of our farmers and workers and the work, unique in history, of our youth, who bear my name” (i.e., Hitler Youth). He blamed the Jews and those working for Jewish interests for the failure of his historic mission and the catastrophe they had brought to Germany and Europe. The German people’s fight against world Jewry, he averred, would eventually go down in history as “the most glorious and valiant manifestation of a nation’s will to existence.” Less than a mile/about a kilometer from Hitler and Braun’s funeral pyre, Private Mikhail Minin risked bullets and bombs to plant the Soviet flag atop the shambles of the German parliament building, the Reichstag, a symbolic present to Joseph Stalin in time for Moscow’s sacred May Day parade. Soldiers had sewn the banner together out of tablecloths the night before. The emblematic moment was reenacted 2 days later by Sergeant Meliton Kantaria for the camera.

Facilitated in part by loudspeaker trucks and airdropped leaflets (Hamburg and Munich were the 2 German radio stations still broadcasting), news of a ceasefire and Hitler’s death spread throughout the capital. Most Berliners rejoiced, tearing up the ubiquitous photographs of Hitler that hung on their apartment walls, but the exuberant feeling was by no means universal. In neutral Portugal, the government ordered 2 days of mourning for the fallen Fuehrer. In Dublin, Ireland’s capital, the Irish prime minister called at the German legation to express his condolences. And in Tokyo, capital of Germany’s still undefeated ally Japan, the German embassy held a memorial service for the deceased head of state. It is believed to be the only memorial service anywhere held for Hitler.

![]()

The Fuehrerbunker and Hitler’s and Braun’s Initial Gravesite

|

Above: Schematic diagram of the Fuehrerbunker (left in image) and the Vorbunker. The 16‑room Vorbunker (“forward bunker,” or antebunker) was located beneath the long reception hall that was added to the rear of the Old Reich Chancellery in 1939. (The hall connected the Old Reich Chancellery on Wilhelmstrasse with the New Reich Chancellery on Vossstrasse.) The Vorbunker was meant to be a temporary air raid shelter for Hitler, his guards, and servants. It was officially called the “Reich Chancellery Air Raid Shelter” until 1943, when construction began that expanded the bunker complex with the addition of the 20‑room Fuehrerbunker over 30 feet/9.1 meters beneath the garden of the Old Reich Chancellery. The 2 bunkers were connected by a flight of stairs.

|  |

Left: Taken in July 1947, this photo shows the massive first emergency exit of the main bunker (erster Notausgang des Hauptbunkers), or the rear entrance to the Fuehrerbunker (no. 21 in the schematic diagram above). Hitler and Braun were cremated in a shell hole in front of the emergency exit. The cone-shaped structure in the center of the photo (no. 37) served as an observation tower and bomb shelter for the guards. An unfinished tower (no. 38), a ventilation tower, is partially hidden behind the tree. Two years earlier, in July 1945, a day before the victors’ Potsdam Conference was to begin, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill stopped at the rear entrance of the Fuehrerbunker, hoping to enter its underground recesses. Told how many flights of stairs down they were, he declined, settling instead on a chair at the rear entrance for a few moments, silent, lost in thought.

![]()

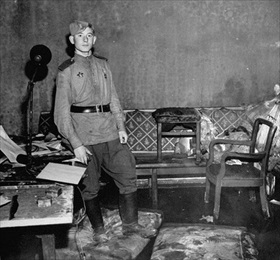

Right: A young Soviet soldier stands reputedly amid the scattered remains of Hitler’s personal study (no. 26), the place of his and his wife’s suicides. A Dutch still life that once hung over the sofa is missing. A photographer for LIFE magazine who visited the Fuehrerbunker soon after the war’s end wrote that “the Russians themselves left little intact or unmolested.” On December 5, 1947, Soviet engineers tried dynamiting Hitler’s bunker complex but had limited success. Both ventilation towers and the entrance structure seen in the picture on the left were destroyed in the blasts. Twelve years later the East German government applied more dynamite to the bunker ruins, then covered everything over with earth. In the second half of the 1980s East German work crews finished demolishing the site and built residential housing and other buildings in the space where the 2 Reich chancelleries, garden, and bunker complex had been. A children’s playground occupies the spot where Hitler’s and Braun’s bodies were burnt.

Death in the Fuehrerbunker: Timeline’s Last Days of Adolf Hitler

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click