HITLER, WIFE CREMATED AFTER SUICIDES

Berlin, Germany · April 30, 1945

On this date in 1945 Adolf Hitler, to all the world the face of unspeakable evil, shot himself in the right temple after he and Eva Braun had poisoned themselves by ingesting cyanide. The Fuehrer’s psychotic desire for an apocalyptic end for Germany—a Wagnerian Goetterdaemmerung—was nearly completed by his death, leaving Berlin’s formal surrender in the hands of its garrison commander, Gen. Helmuth Weidling, two days later.

From the recessed Fuehrerbunker, Hitler’s pall bearers carried the bodies of their troglodyte leader and his wife of 40 hours (and near-secret mistress for 14 years) into the once-beautiful, now desolated gardens of the ruined Old Reich Chancellery. The pall bearers (and former wedding attendants) were Erich Kempka, Hitler’s chauffeur since 1932; Heinz Linge, Hitler’s valet; Martin Bormann, ruthless head of the Reich Chancellery; Joseph Goebbels, ueber-loyal apostle, Hitler diarist, and bombastic Minister of Propaganda; and Dr. Ludwig Stumpfegger, Heinrich Himmler’s former personal physician and the provider of the poison capsules. The two corpses were laid next to each other in the sand on level ground.

Shortly before 3:00 p.m., five barrels of gasoline were poured over their remains and set on fire. In Hitler’s last will and testament, he wrote that he and his wife chose death rather than witness the overthrow and capitulation of his nation. Less than a mile from the funeral pyre, Private Mikhail Minin risked bullets and bombs to plant the Soviet flag atop the shambles of the Reichstag, a symbolic present to Joseph Stalin in time for Moscow’s May Day parade. Soldiers had sewn the banner together out of tablecloths the night before. The emblematic moment was re-enacted two days later for the camera.

Facilitated in part by loudspeaker trucks and airdropped leaflets (Hamburg and Munich were the two German radio stations still broadcasting), news of a ceasefire and Hitler’s death spread throughout the capital. Most Berliners rejoiced, tearing up the ubiquitous photographs of Hitler that hung on their apartment walls, but the exuberant feeling was by no means universal. In neutral Portugal, the government ordered two days of mourning for the fallen Fuehrer. In Dublin, Ireland’s capital, the Irish prime minister called at the German legation to express his condolences. And in Tokyo, capital of Germany’s still undefeated ally Japan, the German embassy held a memorial service for the deceased head of state. It is believed to be the only memorial service anywhere held for Hitler.

![]()

The Fuehrerbunker and Hitler’s and Braun’s Initial Gravesite

|

Above: 3-D representation of the Vorbunker and the Fuehrerbunker. The Vorbunker (“forward bunker”) was located behind the large reception hall, or marble gallery, that was added onto the Old Reich Chancellery in 1939. It was meant to be a temporary air raid shelter for Hitler, his guards, and servants. The bunker was officially called the “Reich Chancellery Air Raid Shelter” until 1943, when construction began that expanded the complex with the addition of the Fuehrerbunker located one level below.

|  |

Left: Taken in July 1947, this photo shows the massive first emergency exit of the main bunker (erster Notausgang des Hauptbunkers), or the rear entrance to the Fuehrerbunker (no. 21 in the schematic diagram above). Hitler and Braun were cremated in a shell hole in front of the emergency exit, the former laid on his back, the latter on her stomach. The cone-shaped structure in the center of the photo (no. 37) served as an observation tower and bomb shelter for the guards. An unfinished tower (no. 38), a ventilation tower, is partially hidden behind the tree. Two years earlier, in July 1945, a day before the victors’ Potsdam Conference was to begin, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill stopped at the rear entrance of the Fuehrerbunker, hoping to enter its underground recesses. Told how many flights of stairs down they were, he declined, settling instead on a chair at the rear entrance for a few moments, silent, lost in thought.

![]()

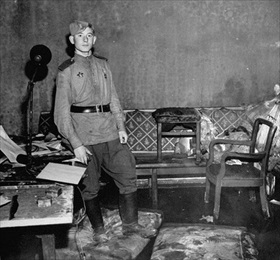

Right: A young Soviet soldier stands reputedly amid the scattered remains of Hitler’s personal study (no. 26), the place of his and his wife’s suicides. A Dutch still life that once hung over the sofa is missing. A photographer for LIFE magazine who visited the Fuehrerbunker soon after the war’s end wrote that “the Russians themselves left little intact or unmolested.” On December 5, 1947, Soviet engineers tried dynamiting Hitler’s bunker complex but had limited success. Both ventilation towers and the entrance structure seen in the picture on the left were destroyed in the blasts. Twelve years later the East German government applied more dynamite to the bunker ruins, then covered everything over with earth. In the second half of the 1980s East German work crews finished demolishing the site and built residential housing and other buildings in the space where the two Reich chancelleries, garden, and bunker complex had been. A children’s playground occupies the spot where Hitler’s and Braun’s bodies were burnt.

Death in the Fuehrerbunker: Timeline’s Last Days of Adolf Hitler

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click