HISTORIC U.S. PACIFIC VICTORY IN SOLOMONS

Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands • February 9, 1943

On this date in 1943 Guadalcanal, the largest of the nearly one thousand islands in the Solomon Islands chain, was declared secure. U.S. Marines had landed on the previously obscure island beginning on August 7, 1942, in the first major offensive by Allied forces against Japan. Operation Watchtower, as the air-sea-land campaign was codenamed, was intended to deny the Japanese use of Guadalcanal Island from which they could interdict supply and communication routes between the U.S., Australia, and New Zealand, as well as be a U.S. springboard to seize other islands to the north.

The Marines swiftly overcame the small Japanese garrison. But the Japanese high command placed the utmost priority on retaking this southwestern Pacific island of tropical rainforest and jungle and to finishing the building of their airstrip, which the Americans later renamed Henderson Field (east of Honiara on the map below). In late August 1942 the Japanese began pouring in reinforcements from their main Pacific base at nearby Rabaul on the island of New Britain (part of Papua New Guinea), supported by aircraft and naval guns. Three major land battles, 7 large naval battles, and the almost daily aerial battles were capped by the decisive Naval Battle of Guadalcanal (November 12–15, 1942), in which the last Japanese attempt to bombard Henderson Field from the sea and put enough troops ashore to retake it was defeated.

The Japanese faced mounting losses—roughly 30,000 experienced Japanese troops were killed during the ground campaign—as well as supply difficulties that were brought painfully home when the “Cactus Air Force,” the ensemble of Allied air power assigned to the island of Guadalcanal, sank 7 of 11 Japanese transports at the end of November. Despite it all the Japanese managed to successfully evacuate their starving and disease-ridden garrison to neighboring Bougainville Island between February 1 and 7, 1943.

The Guadalcanal Campaign had important implications for the combatants. In a narrow sense, the U.S. Marine Corps came of age as a land fighting force during the difficult days on Guadalcanal. In a larger sense, U.S. service members from all branches—Marine Corps, Army, and Navy—had beaten Japan’s best land, air, and naval forces and had halted the Japanese advance in the South Pacific. Henceforth, Americans in service uniforms and those on the home front could view the outcome of the war with new optimism. For forward-seeing Japanese, however, Guadalcanal would emerge as the turning point in the Pacific conflict, the first in a long string of disasters that would inexorably lead to the surrender and occupation of their nation.

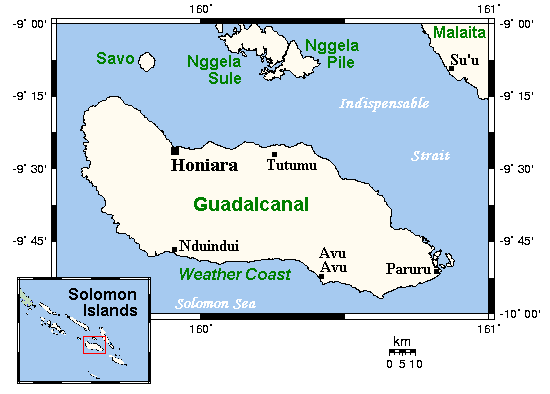

Guadalcanal: Scene of Bitter Fighting Between U.S. and Japanese Forces in the Southwestern Pacific, August 1942 to February 1943

|

Above: Guadalcanal Island and its location within the Solomon Islands. The Solomons are roughly 500 miles/805 kilometers east of Papua New Guinea and 1,100 miles/1,770 kilometers northeast of Australia. Ninety miles/145 kilometers long on a northwest-southeast axis and an average of 25 miles/40 kilometers wide, Guadalcanal is a forbidding terrain of mountains and dormant volcanoes up to 7,600 feet/2,316 meters high, steep ravines and deep streams, mangrove swamps, and a generally even coastline with no natural harbors. Nasty critters, including crocodiles, populated the island. The 3‑dimensional Guadalcanal Campaign (land-sea-air) stretched both adversaries to the breaking point. The storied battle for the island lasted 6 months, involved nearly 1 million men, and stopped Japanese expansion in the Southwest and Central Pacific.

|  |

Left: Escorted by a task force that included 3 carriers, 11,000 men from the 1st Marine Division, under the command of Maj. Gen. Alexander Vandegrift, stormed ashore on Guadalcanal’s beaches on August 7, 1942, exactly 8 months from the date Pearl Harbor was bombed. On October 13 the first Army unit, the 164th Infantry, came ashore to reinforce the Marines. (Up till then, U.S. Army troops were chiefly funneled to Europe.) The Allies overwhelmed the outnumbered Japanese defenders, who had occupied the islands since mid‑1942, and captured nearby Tulagi and Florida islands (identified as Nggela Sule and Nggela Pile on the map), as well as the unfinished airfield at Lunga Point. Powerful U.S. and Australian warships and transports supported the landings.

![]()

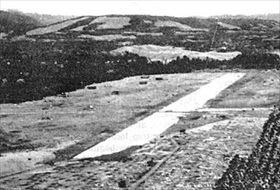

Right: Aerial view of Lunga Field (Henderson Field), Guadalcanal, July 1942, under construction by a mixed labor force of Japanese and Koreans. The Marines’ landing at Lunga Point was to capture the dirt-and-gravel airstrip before it could become operational. (The base was large enough to accommodate over 100 aircraft.) After capturing it, American forces went on to complete it. Henderson Field, named for the first Marine pilot killed during the Battle of Midway (June 4–7, 1942), was abandoned after the war, but it reopened in 1969 as a modernized civilian airport capable of accommodating large jets.

|  |

Left: Japanese reinforcements load onto a destroyer for the “ant run,” as Japanese soldiers called the naval dash down the “Slot” to Guadalcanal in 1942. The “Tokyo Express” was the name given by Allied forces to fast Japanese ships (mainly destroyers but also submarines) that used the cover of night to deliver personnel, artillery, vehicles, food, and other supplies to enemy forces operating in and around New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

![]()

Right: Fresh troops from the 2nd Marine Division during a halt on Guadalcanal, November 1942. Allied ground strength, primarily American, came to 60,000 vs. 36,200 for the Japanese. During the 6‑month campaign, the Japanese suffered 31,000 dead and 1,000 captured out of 36,200 combatants. U.S. dead numbered 7,100.

HBO Presentation: Inside the Battle of Guadalcanal

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click