HIROHITO TO NATION: TIME TO “BEAR THE UNBEARABLE”

Tokyo, Japan • August 14, 1945

Two days after the United States had dropped a second atomic bomb on a major Japanese city, this on Nagasaki on August 9, Emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa) personally intervened during an Imperial Conference (Gozen Kaigi) to let diehard hawks in his government and armed services know that for Japan’s sake the war must end.

Notwithstanding the limited and ceremonial role the emperor played at imperial conferences, Hirohito drew upon the power of his moral and spiritual leadership to issue the first of 2 seidans (imperial personal opinions). In the first he proposed accepting the provisions of the Potsdam Declaration issued by the United States, Great Britain, and China on July 26, 1945, that demanded Japan’s capitulation. Already the promise in the declaration of “prompt and utter destruction” if Japan did not comply was confirmed, not only by the atomic weapons that obliterated Hiroshima on August 6 and Nagasaki 3 days later, but by reports from Japan’s Air Defense General Headquarters: Out of 206 cities, 44 had been almost completely wiped out, while 37 others, including the capital Tokyo, had lost over 30 percent of their built-up areas. Almost 2 million military personnel and civilians were dead, with another 8 million wounded or homeless. “I do not wish my people to fall into deeper distress or destroy our culture,” the emperor told his audience, which included obstinate members of the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War. “The time had come when we must bear the unbearable.”

In a second deeply moving imperial seidan on this date, August 14, the emperor accepted the limitations that the Allies had imposed on his sovereign prerogative to rule the country after its surrender: “No matter what happens to me, I want to save the lives of all my people. If we continue the war, the whole country will be reduced to ashes, and I cannot endure the thought of letting my people suffer any longer.”

In an odd turn of events perhaps, the U.S. Office of War Information assisted Emperor Hirohito by publicizing the calamity Japan faced short of surrender and, in so doing, boosting the peace momentum. Two days before, on August 12, the OWI, using radio and B‑29 leaflet drops over major Japanese cities, disclosed the news of the Japanese government’s secret negotiations with the Allies. Hirohito found himself in a quandary: civilians, rattled in every direction, now knew of their emperor’s effort to conclude the war but ominously so did younger militants in his military.

Fearing an army coup the emperor took an added measure on August 14 to ensure the war ended peacefully for his 70 million subjects. In an action without precedent, Hirohito issued an imperial decree (rescript) announcing his country’s capitulation, to be delivered to both the Allies through diplomatic channels and the nation in his own voice in a radio address the next day. A faction of the military, aware that the broadcast would doom any efforts to prolong the war, ordered elements of the Imperial Guard Division to take over Hirohito’s palace on the night of August 14/15 and seize the recording. The coup failed. The insurgents could not break into the emperor’s basement bunker, where a pale Hirohito and staff had taken refuge, or find the recordings. At noon on August 15 a stunned populace listened to their emperor’s high, shaking, unfamiliar voice over the airwaves effectively announcing the end of World War II.

U.S. Propaganda Assists Hirohito in Closing Peace Deal

|  |

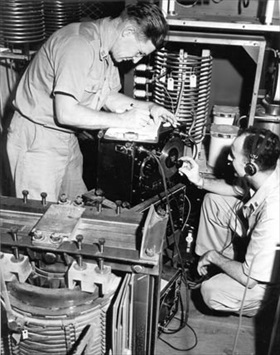

Left: Established by an executive order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in June 1942, the U.S. Office of War Information was empowered to conduct propaganda campaigns abroad that would contribute to an Allied victory against the Axis. Propaganda included print and news media. The OWI bombarded Japan with radio messages through its 50,000-watt station on Saipan in the Marianas, Radio KSAI. The station also picked up 100,000-watt shortwave transmissions from the OWI station in Honolulu, Hawaii, and relayed them to the Japanese homeland, where censored news was the norm, as well as to Japanese-occupied territories, where enemy soldiers were tempted into surrendering by the promise of fair treatment as prisoners of war. Japanese language radio broadcasts consisted of news reports on the true status of the war, bombing warnings, and messages from Japanese POWs held on Saipan urging their countrymen to surrender. On the day the text of the Potsdam Declaration was released, July 26, 1945, KSAI began broadcasting the surrender terms to the Japanese nation at regular intervals. Thus, Japanese officials learned of the Allies’ conditions for ending the war a day ahead of the official communication sent through diplomatic channels. In this photo OWI personnel are seen adjusting the KSAI radio transmitter to new frequencies to avoid jamming by Japan.

![]()

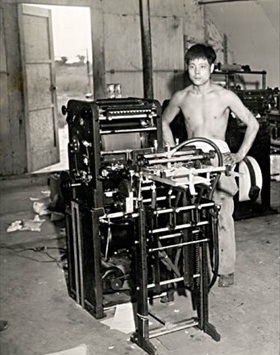

Right: A young Japanese POW operates an OWI printing press on Saipan that turned out newspapers and leaflets (mostly done “four up” on 8½ x 11‑in. paper) for delivery to the Home Islands and to combat zones. Less than 48 hours after Japan’s surrender offer of August 9 was received in Washington, D.C., three-quarters of a million leaflets giving notification of Japan’s surrender offer and the Allies’ acceptance thereof had been printed on OWI’s 3 high-speed presses. By the next afternoon, production of OWI leaflet #2117 totaled well over 5 million copies.

|  |

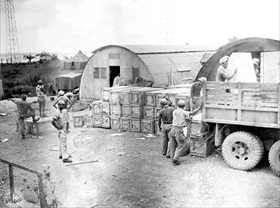

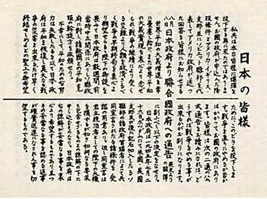

Above: Loading OWI leaflets for transport to a U.S. airfield on Saipan (Left panel). Saipan’s naval base designated 2 15‑member Navy crews to pack the Japanese capitulation leaflets (Right panel) into bomb casings for delivery by B‑29s. Beginning August 12 and for the next 3 days aircraft runs departed Saipan for major population centers such as Tokyo, Kobe, Osaka, Kyoto, and Nagoya to airdrop news of Japan’s secret peace negotiations with the Allies. The 4‑in. x 5‑in. leaflets, the text of which had been radio-phoned from Washington, D.C., rained down by the millions, roughly 5.5 million on the night of August 13/14. “These American planes [read the Japanese text] are not dropping bombs on you today. American planes are dropping these leaflets instead because the Japanese Government has offered to surrender, and every Japanese has a right to know the terms of that offer and the reply made to it by the United States Government on behalf of itself, the British, the Chinese, and the Russians. Your government now has a chance to end the war immediately.” The next 2 paragraphs described the Japanese surrender offer verbatim and the Allies’ willingness to accept the offer. KSAI radio hammered the message home hour after hour. Through leaflet drops and by radio ordinary Japanese learned for the first time that their government was trying to surrender. Incredibly, a full 72 hours passed before Japan’s leadership, including Emperor Hirohito who found a 2117 leaflet on his palace grounds, learned through diplomatic channels of the Allies’ acceptance of their surrender offer.

Timeline’s “The Bloody History of the Pacific Theater: Battles Won and Lost”

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click