HIROHITO DECIDES FATE OF HIS NATION

Tokyo, Japan • August 12, 1945

In 1945 the endgame in Europe was to capture Berlin, the epicenter of Nazi resistance, which the Red Army did in the last week of April. On May 7 and 8, 1945, Adolf Hitler’s political heir, Adm. Karl Doenitz, surrendered Nazi Germany unconditionally to the Allies. The endgame in the Pacific War seemed to be the incineration of Japan. As President Harry S. Truman stated on August 6, following the atomic bombing of Hiroshima: “We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories, and their communications. Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan’s power to make war.” The Japanese warlords, the president went on to say, “may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth.” It was obvious to every combatant nation in the Asia Pacific conflict that a negotiated peace remotely favorable to Japan was off the table.

On this date, August 12, 1945, in Tokyo, Japanese Emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa) informed his family of his decision to order his country’s surrender to the Allies. Until August 9, the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War (all military officers with the exception of Foreign Affairs Minister Shigenori Tōgō) had set 4 preconditions for Japan’s surrender. But on this day the emperor ordered his Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal to “quickly control the situation” in light of the Soviet Union’s entry into the war on August 9. (August 9 was also the date the U.S. dropped a second atomic bomb on Japan, this on the city of Nagasaki. Another atomic bombing was in the planning stages just as soon as a third bomb, which was in New Mexico, had been flown to the Pacific and made ready for delivery sometime after August 24 if Japan hadn’t surrendered. Truman ruled out further atomic bombings of Japan without his express permission the day after Nagasaki was immolated.

Then Hirohito held an impromptu Imperial Conference (Gozen Kaigi) that included both the “Big Six” war council members and the entire cabinet of Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki. During the Imperial Conference the emperor authorized Shigenori Tōgō (the same Foreign Affairs minister who had signed the declaration of war on the U.S. in 1941) to notify the Allies that Japan would accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration of July 26, 1945 (“unconditional surrender” over the alternative of “prompt and utter destruction”). Japanese leaders insisted on one condition: the surrender must not compromise the prerogatives of the emperor as a sovereign ruler. Early on the morning of August 10, 1945, the Japanese Foreign Ministry telegrammed the Allies (via the Swiss legation in Washington, D.C.) of their government’s decision. The U.S., British, Chinese, and Soviet governments formally replied as one on August 11.

The Allies’ August 11 response (it was August 12 when it arrived in Tokyo), known as the Byrnes Note after the U.S. Secretary of State who crafted it, seemed to leave intact the principle of the preservation of the Throne: “The ultimate form of government of Japan shall, in accordance with the Potsdam Declaration, be established by the freely expressed will of the Japanese people.” It was a condition Hirohito could live with: “I think the [U.S.] reply is all right,” the emperor told his foreign minister. “You had better proceed to accept the note as it is.” And so on August 14 Hirohito recorded Japan’s capitulation announcement that was broadcast to the nation the next day, August 15. Speaking frankly to his subjects Hirohito acknowledged the awesome loss of life and destruction of property caused by 2 atomic bombings and the potential for more of the same, saying, “Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.” After the broadcast the emperor’s war cabinet resigned en masse.

Inescapable Annihilation or Unconditional Surrender, Japan, August–September 1945

|  |

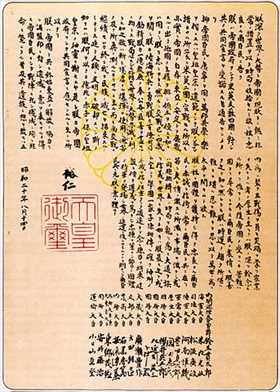

Left: Emperor Hirohito’s Rescript on the Termination of the War. The rescript was written on August 14, recorded on a phonograph record, and broadcast to Japanese citizens at noon on August 15, 1945. Hirohito’s Gyokuon-hōsō (lit. “Jewel Voice Broadcast”) made no direct reference to Japan’s surrender or defeat. Neither did it contain the words “apologize” or “sorry.” Instead, the emperor said he had instructed his government to accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration fully. This circumlocution confused many listeners who were not sure if Japan had in fact surrendered or if the emperor was exhorting his subjects to resist an enemy invasion. The poor audio quality of the radio broadcast, as well as the formal courtly language in which the speech was composed and delivered, added to the confusion. Curiously, Hirohito made no mention in his broadcast of also being motivated to terminate the war by the Soviet Union’s August 8 invasion of Japanese-occupied Manchuria (Japan’s puppet state of Manchukuo) on the Chinese mainland, though clearly it weighed on his mind in the decisions he and his councilors made between August 8 and 14, 1945.

![]()

Right: Recently appointed Japanese Foreign Affairs Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu, along with Chief of the Army General Staff and Supreme War Council member Gen. Yoshijirō Umezu, signs the Japanese Instrument of Surrender on board the USS Missouri as Gen. Richard K. Sutherland and Toshikazu Kase, a high-ranking Japanese Foreign Ministry official, watch. Tokyo Bay, September 2, 1945. (A revision to the Byrnes Note dropped the requirement that Hirohito personally sign the surrender document.) When Shigemitsu appeared confused as to where to place his signature, Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers and master of ceremonies for the surrender formalities, barked to Sutherland, “Show him where to sign.” Shigemitsu, along with his predecessor in the Foreign Affairs office, Shigenori Tōgō, who advocated Japanese surrender in the summer of 1945, and Gen. Umezu were tried as war criminals at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo and imprisoned. Hirohito escaped their fate.

Footage of the Moment the Japanese Surrendered Aboard the USS Missouri

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click