HIROHITO BRIEFED ON HIROSHIMA CATASTROPHE

Tokyo, Japan • August 8, 1945

On this date in 1945, Japan’s Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō, the government’s leading civilian proponent of a peace settlement with the Allies, visited Emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa) at his palace to brief him on Hiroshima’s ruin by (as Hirohito later characterized it) “a new and most cruel bomb.” That city of 340,000–350,000 people had been rubbed out in a blinding, instant flash on the morning of August 6. It wasn’t until the next day, however, that officials in Tokyo received the initial damage reports, partial and a bit confusing. Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki’s cabinet reviewed the reports against the backdrop of U.S. President Harry S. Truman’s demand for Japan’s immediate surrender, as stated in the Potsdam Declaration. The July 26 ultimatum by the U.S., Great Britain, and China assured Japan of that country’s “prompt and utter destruction” if it did not surrender. (The three signatories ruled out negotiation and third-party mediation.) Citing U.S. Japanese-language radio broadcasts and American B‑29 leaflet drops that described Hiroshima’s awful fate, with more bombing promised, Tōgō pressed his case for ending the war by quickly surrendering the country and, in the process, calming the emperor’s now panicky subjects.

The elderly prime minister, after reviewing the text of the Potsdam Declaration, ignored it, “killing it with silence” (mokusatsu, i.e., silent contempt). Suzuki scornfully dismissed it as a rehash (yakinaoshi) of the Allies’ earlier declaration, issued by the same parties, on November 27, 1943, in Cairo, Egypt. “We will do our utmost to fight the war to the bitter end,” Suzuki told the Japanese press. The Japanese-run Hong Kong News called the declaration a piece of unqualified impudence. Meanwhile, Foreign Minister Tōgō vainly sought to learn the Soviets’ take on the 1945 ultimatum: the Soviets were not a party to it, so conceivably they might mediate favorable surrender terms with the Americans in return for Japanese-held territory in East Asia. Most military officers, especially army officers, opposed laying down their arms at all.

In spite of the catastrophe inflicted on Hiroshima two days earlier, members of the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War (Saikō sensō shidō kaigi) were deadlocked regarding what steps the government should take. Calling an Imperial Conference (Gozen Kaigi) on the night of August 9/10, Hirohito, in an unprecedented act, personally intervened by issuing a sacred imperial decision (seidan) to end the war and ruling out approaching the Soviet Union or neutral Sweden and Switzerland for better surrender terms than outlined by the Potsdam Declaration. “I have given serious thought to the situation prevailing at home and abroad,” he told his august audience, “and I have concluded that continuing the war can only mean destruction for the nation and a prolongation of bloodshed and cruelty in the world. I cannot bear to see my innocent people suffer any longer! Ending the war is the only way to restore world peace and relieve the nation from the dreadful distress with which it is burdened.”

By now the Soviet Union had entered the war against Japan by invading Japanese-occupied Manchuria on the Chinese mainland (August 8/9), and a second U.S. atomic bomb had leveled another Japanese city (Nagasaki) on August 9. Hirohito, who had expressed an interest in diplomatic maneuvers to end the war back in early June, ordered an Imperial Rescript drafted, which was submitted to the Suzuki cabinet. On August 14 the emperor recorded his nation’s capitulation announcement, which was broadcast to his subjects on August 15. From being an enthusiastic supporter of the Pacific War in 1941, Hirohito managed to quit the war without quite losing it. In the role of a lifetime, Hirohito seized—however undeserved—the high moral ground from his enemies by playing on the meaning of his name (Hirohito means “abundant benevolence”), claiming that his seidan had broken the impasse in Japan’s military-dominated government and restored peace to his war-weary land. He acted above all, he told his subjects, to save the nation from “ultimate collapse and obliteration” by paving “the way for a grand peace for all the generations to come.”

![]()

Shocking Japan into Surrendering, August 1945

|  |

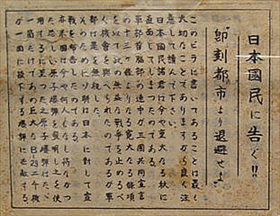

Left: This leaflet by the U.S. Office of War Information (OWI) was dropped on Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and 33 other Japanese cities on August 1, 1945. It shows five B‑29s dropping incendiary bombs over Yokohama on May 29, 1945. The Japanese text on the reverse side of the leaflet carried the warning: “Read this carefully as it may save your life or the life of a relative or friend. In the next few days, some or all of the [12] cities named on the [front] side will be destroyed by American bombs. . . . We cannot promise that only these cities will be among those attacked [Hiroshima was not named on the front—ed.] but some or all of them will be, so heed this warning and evacuate these cities immediately.”

![]()

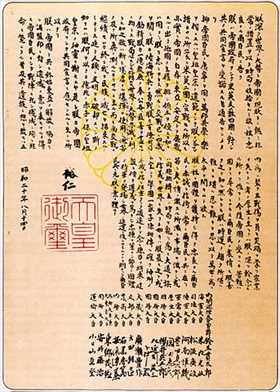

Right: An OWI leaflet dropped from a B‑29 on Japan after the bombing of Hiroshima. Translation: “Notice to the Japanese People! Evacuate the city immediately. What this leaflet contains is extremely important, so please read carefully. The Japanese people are facing an extremely important autumn. Your military leaders were presented with thirteen articles for surrender [i.e., Potsdam Declaration] by our three-country alliance to put an end to this unprofitable war. This proposal was ignored by your army leaders. Because of this the Soviet Republic intervened. In addition, the United States has developed an atom bomb, which had not been done by any nation before. It has been determined to employ this frightening bomb. One atom bomb has the destructive power of 2000 B‑29s. This frightening fact should be understood by you by observing what kind of situation was caused when only one was dropped on Hiroshima.” This leaflet caused widespread panic in many Japanese cities.

|  |

Left: Wartime photograph of Emperor Hirohito in a brown Army uniform, presiding head of an Imperial Conference (Gozen Kaigi), seated on his throne on a small, raised platform in front of a folding screen at one end of the high-ceiling conference room. To the emperor’s left and right, behind long tables, sat his imperial generals, admirals, and ministers. Convened by the Japanese government in Hirohito’s presence, Imperial Conferences were extraconstitutional conferences that focused on foreign affairs of grave national importance. In the early morning hours of August 10, Hirohito, at the request of Prime Minister Suzuki, addressed the forum in a voice euphemistically called the “Voice of the Crane” and cast the die for embracing the Potsdam Declaration and ending the war. Alluding to the number of U.S. air raids “escalating every day” (but not to the ghastly fate of Hiroshima and Nagasaki), the emperor opined: “I do not wish my people to fall into deeper distress or destroy our culture, nor do I wish to bring misery to mankind. The time has come when we must bear the unbearable.” Suzuki and his cabinet met immediately afterwards and unanimously endorsed the emperor’s personal opinion (seidan), turning it into a state decision to neutralize military hardliners. Four days later, in a second Imperial Conference, Hirohito accepted U.S. surrender terms regarding occupation of the country and limits on his authority and the authority of the Japanese government to rule the state. Again, the emperor’s seidan was transformed into an official government decision.

![]()

Right: Emperor Hirohito’s Rescript on the Termination of the War. The rescript was written on August 14 by Hirohito’s ministers of state at his direction, recorded on a phonograph record at the Tokyo facilities of the Japan Broadcasting Corporation by a tearful emperor in his high, shaking, unfamiliar voice, and broadcast to Japanese citizens at noon on August 15, 1945. Hirohito’s Gyokuon-hōsō (lit. “Jewel Voice Broadcast”) made no direct reference to Japan’s surrender or defeat. Neither did it contain the words “apologize” or “sorry.” Instead, the emperor said he had instructed his government to accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration fully without describing them. This circumlocution confused many listeners who were not sure if Japan had surrendered or if the emperor was exhorting his subjects to resist an enemy invasion. The poor audio quality of the historic radio broadcast, as well as the formal courtly language in which the speech was delivered, added to the confusion. A radio announcer’s rereading of emperor’s rescript in ordinary Japanese attempted to clarify its meaning.

Planning the Defeat of Japan Down to the Last Bomb, a U.S. War Department Presentation (in color)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click