HELLISH FIREBOMBING RAVAGES DRESDEN

Dresden, Germany • February 13, 1945

On this night in 1945, Fat (or Shrove) Tuesday, and over the next day, Ash Wednesday, some 1,300 British and American bombers appeared over largely untouched Dresden in Eastern Germany. A city of 642,000 (1939) swelled by 300,000 refugees fleeing from fighting on the Eastern Front, Dresden, 120 miles/310 kilometers south of Berlin, was the ancient capital of the German state of Saxony and the Third Reich’s seventh largest city. In 3 successive waves the bombers delivered a massive onslaught of almost 4,000 tons of ordnance—high explosives followed by incendiaries—on the city long known as the “Florence of the Elbe” on account of its churches, concert halls, beautiful palaces, and public gardens.

The Dresden raid had originally been intended to target suburban industries, railroad classification (or marshaling) yards, and bridges over which more than 20 German troop trains passed to and from the Eastern Front nearly every day in early February. Instead the bombs fell on the centuries-old baroque city center. Fires started by the first wave of British bombers were augmented by incendiaries dropped by the second. The flames quickly combined to form a raging terror storm that consumed more than 12 square miles/31 square kilometers, set the Elbe River on fire, and burned, blew apart, or asphyxiated roughly 25,000 people as they huddled in basements and bomb shelters. Shortly after noon on February 14, heavy bombers of the U.S. Eighth Air Force, which had set up shop in Britain in 1942, swept in, targeting Dresden’s rail yards and western neighborhoods and suburbs. About 380,000 people were made homeless in the 3 Allied air raids, while roughly 78,000 buildings were destroyed and tens of thousands more damaged.

Six years before, on September 25, 1939, the German Luftwaffe had introduced the concept of firebombing major population centers by dropping incendiary and high-explosive bombs on the Polish capital, Warsaw. (See photo essay below.) Less than a year later, on May 14, 1940, the Luftwaffe bombed the Dutch city of Rotterdam, igniting a firestorm that killed nearly 900 civilians and left 30,000 homeless. The Luftwaffe carried out firebombing raids on an ever-larger scale with nighttime attacks on the British capital, London, and other British cities in 1940–1941 (Blitz).

On July 24, 1943, a British bomber fleet over the North German city of Hamburg upped the ante when it dropped high-explosive bombs, followed by incendiaries, for a total of 5 times the ordnance of any German raid on London. The firestorm in the third wave of Operation Gomorrah killed 45,000 Hamburg residents and refugees. Out of a populace of 1 million, 800,000 were rendered homeless when 12 square miles/31 square kilometers of the city were completely leveled, causing an enormous humanitarian crisis. A German official described Hamburg as “beyond all human recognition.” The Japanese capital, Tokyo, was the worst-ravaged city of any firebombing when on March 9–10, 1945, 90,000 civilians were killed and 40,000 more swept up as the conflagration spread. However, the Dresden bombing, coming in the last 3 months of the war, emerged as one of the most controversial episodes of World War II.

Inflicting Material Destruction from the Air: German and Allied Examples

|  |

Left: On September 10, 1939 (“Bloody Sunday”), the Luftwaffe launched 17 air raids on Warsaw, Poland’s capital. On September 25, “Black Monday,” 1,200 sorties dropped 500 tons of bombs that generated raging fires, as the city’s water mains had been badly damaged. Smoke from the inferno rose 10,000 feet/3,333 meters into the air and was visible 70 miles/113 kilometers away. Never was such a violent combination of aerial and artillery bombardment inflicted on a European city in the space of a month. By October Warsaw, whose original 3 million residents were reduced by 50–60,000 deaths, resembled a city of the dead.![]()

Right: On May 14, 1940, German bombers razed Rotterdam’s medieval city center to the ground in less than an hour, killing nearly 900 inhabitants, destroying 25,000 homes, 24 churches, and 62 schools. Roughly 80,000 residents were rendered homeless not only by the afternoon’s bombing but also by the fires that raged after the bombardment, ravaging the city for weeks. Photo was taken after the removal of the debris.

|  |

Left: The Great Dome of St Paul’s Cathedral, undamaged, ringed by clouds of smoke rising from the burning city of London. John Topham’s iconic photograph was taken on December 29, 1940, the 114th night of the London Blitz. The Luftwaffe dropped more than 24,000 high-explosive bombs and 100,000 incendiary bombs on the British capital that day and the next. For 57 consecutive nights heavy German raids damaged or destroyed more than a million buildings. About 20,000 Londoners died in the raids.

![]()

Right: The ruins of Dresden’s city center (“Altstadt”). Despite being home to 127 medium-to-large factories and workshops that supplied the German Army with matériel (per the German Weapons Office), such as aircraft engines, machine tools, small arms, optical instruments, and poison gas, and employed 50,000 workers, Dresden was woefully unprepared for a major aerial attack. Some 1,249 British and American bombers unloaded more than 3,900 tons of incendiary and high-explosive bombs on the center of the city, causing a firestorm that incinerated 15 square miles/39 square kilometers and between 22,700 and 25,000 people. Temperatures inside Dresden’s famous cathedral, the 18th-century Frauenkirche (Church of Our Lady), reached an estimated 1,832°F/1,000°C before the 300‑foot‑tall/91‑meter‑tall church collapsed. Later the U.S. Eighth Air Force dropped 2,800 more tons of bombs on Dresden in 3 other attacks before the war’s end.

|  |

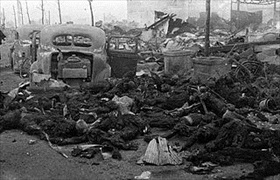

Above: Tokyo after the March 9–10, 1945, firebombing by 334 U.S. B‑29 Superfortresses stationed in the Marianas. The Dante-esque raid, known as Operation Meetinghouse (“Meetinghouse” being a code term for the urban area of the Japanese capital), proved the single-most destructive bombing raid in history: 267,000 mostly wooden buildings in a 16‑square-mile/41.4‑square-kilometer area were devoured by raging fires and an estimated 100,000 killed—the highest loss of life of any aerial bombardment of the war. The Superforts’ primary weapon was the finned 500‑pound/227‑kilogram E‑46 “aimable cluster” bomb, typically 40 bombs to a plane. Each bomb contained 47 small napalm- (jelled gasoline-) filled bomblets, called M‑69s (nicknamed “Tokyo Calling Cards”). The M‑69s were packed inside the E‑46 mother bomb, which was designed to open and scatter its lethal contents at 2,000 or 2,500 feet/666 or 762 meters above ground. Upon colliding with an object, the M‑69 timing fuse burned for 3–5 seconds and then a white phosphorus charge ignited and propelled the incendiary up to 100 feet/30 meters in several flaming sticky globs, instantly starting multiple intense fires. Other weapons in the March raid were the E‑28 incendiary cluster bomb and the M‑47 petroleum-based bomb.

Dresden Firebombing: “Florence of the Elbe” Bombed and Rebuilt

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click