HALYARD MISSION RESCUES TRAPPED U.S. AIRMEN IN YUGOSLAVIA

Boljanić, German-Occupied Yugoslavia • December 27, 1944

On this date in December 1944 the last 20 U.S. airmen were extracted in a hazardous Balkan air rescue courtesy of the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), forerunner to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Operation Halyard (aka Halyard Mission) began nearly 5 months earlier on August 2, though it had been in the planning stage for over a half-month before that. The plan was to parachute-drop a small team of OSS agents and some medical supplies into a remote and rugged part of German-occupied Serbia. There several hundred courageous Serbian villagers and almost 10,000 Chetnik guerrillas led by ex-Yugoslav Army colonel, now general Dragoljub “Draža” Mihailović (also spelled Draja Mihailovich) sheltered and fed U.S. crewmen who had bailed out of flak-damaged aircraft over Yugoslavia on round-trip bombing runs from Allied-held Italian airstrips to chiefly Romanian oilfields. Romania supplied as much as 35 percent of Europe’s Axis petroleum needs and had become Nazi Germany’s single most important fuel source.

Halyard’s team members were seconded to the U.S. Fifteenth Air Force headquartered on Italy’s east coast at Bari, which provided both the long-range, 4‑engine bombers that both struck Romanian oilfields, the most famous being at Ploesti (Ploiești) 37 miles/60 km north of the capital Bucharest, and the unarmed twin-engine C‑47 transports that plucked the downed airmen from behind German lines. The covert rescue was the largest, most successful operation of its kind in history. Evacuated irregularly over a 21‑week period were 432 U.S. and 80 Allied personnel. Miraculously, not one rescue aircraft or person was lost.

After the first parachute insertion into the remote mountain village of Pranjani, Mihailović’s headquarters, by a 3‑man Halyard team on August 2, 1944, OSS operatives and Chetnik guerrillas assembled over 250 stranded airmen at the nearby newly lengthened Pranjani landing strip disguised as a farm meadow. More airmen streamed into Pranjani every day adding several hundred more to the headcount of men trapped behind enemy lines. As previously mentioned, the stranded fliers had been quartered in the cottages and barns of locals at great risk to their hosts and dispersed over a 10‑mile/16 km radius. Twenty-six fliers awaiting evacuation suffered from serious infections or had been injured or wounded.

On the clear but dark night of August 9/10, 1944, and twice in broad daylight the next morning, a total of 16 lumbering C‑47 cargo planes piloted by the fearless fliers of 60th Troop Carrier Command flew 272 Allied men from enemy-held Serbia to safety in Italy. Separate from the rescued U.S. airmen were 4 Frenchmen, 9 Italians, 6 Brits, and 12 Soviets. The August 10 fighter escort duties for the 2 daylight streams of Pranjani-bound C‑47 cargo planes were split between 50 or so single-engine North American P‑51 Mustangs and twin-engine Lockheed P‑38 Lightnings.

Scarcely missing a beat, some 210 additional airmen were evacuated from Pranjani on August 12, 15, and 18, again in C‑47s with fighter escorts. After that the Halyard Mission was forced on its back foot by festering ethnic and political conflicts in war-torn Yugoslavia. The Chetniks’ sworn enemies under communist-leaning Partisan leader Marshal Josip Broz Tito had, in fighting the German occupiers, seized control of all Yugoslav provinces save Serbia and parts of Bosnia. Mihailović’s Serbian warriors, along with the Halyard team and the remaining downed U.S. airmen, were now in Tito’s crosshairs as they fled their home base north to Western Serbia, taking sanctuary in the villages of Koceljeva and later Boljanić, which is in today’s Bosnia and Herzegovina—all the while adding to their motley collection of stranded airmen. At Koceljeva’s improvised airstrip 20 airmen were evacuated on September 17, and from the Boljanić airstrip 15 airmen on the first day of November and 20 airmen on December 27, 1944, the day Halyard quietly shut down.

OSS Halyard Mission, August 2 to December 27, 1944

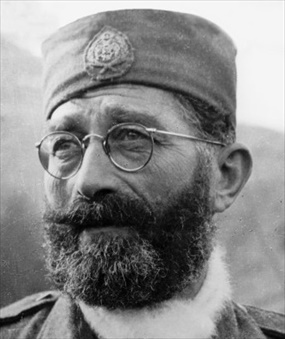

|  |

Left: Dragoljub “Draža” Mihailović (1893–1946) saw combat during World War I, and by the mid‑1930s he had achieved the rank of colonel in the Royal Yugoslav Army. A royalist and nationalist his whole life, Mihailović organized the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army (Chetniks) into a guerrilla force following the German invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941. In the long run the charismatic Serb leader remained anti-Axis but might collaborate or merely reach an accommodation with German and Italian occupiers when he saw an advantage for his side; Mihailović called it “using the enemy.” At the end of 1943 both the U.S. government nudged by the British government, which in turn was nudged by a mole in the service of the Soviet Union to advance Tito’s cause and exaggerate claims of Mihailović’s supposed transgressions and weaknesses, withdrew their favor from what Time magazine once called (May 25, 1942) “the greatest guerrilla fighter of Europe.” Mihailović’s unwavering desire to care for, safeguard, and return at any cost downed Allied flyers across the Adriatic Sea to safety in Italy in an OSS-sponsored rescue operation garnered Anglo-American appreciation short of military and financial aid.

![]()

Right: Center in photo, Chetnik resistance leader Gen. Draja Mihailović converses with a group of his senior commanders, May 1943, in the Lim River valley after a narrow escape from a failed German-Italian joint operation (Case Black) against Tito’s Partisans and Mihailović’s Chetniks in Southeastern Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro. By the end of World War II, the Chetniks’ ranks had been seriously depleted in a brutal civil war with their left-leaning Partisan rivals. (To be fair, many Partisans were anti-German and nothing more.) Just a handful of Chetniks found sanctuary in a mountainous area. The holdouts, including Mihailović, were captured by troops of the new Tito government’s internal security apparatus on March 13, 1946. The 50‑year‑old Chetnik hero of Serbian resistance was tried and convicted of high treason and war crimes in a Stalinist-style dog-and-pony show attended by over 1,100 spectators and journalists. Four months later Mihailović was executed by firing squad in Yugoslavia’s capital Belgrade and buried in an unmarked grave.

|  |

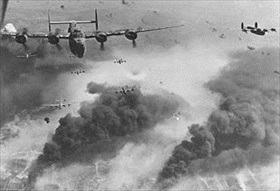

Left: In Operation Tidal Wave on August 1, 1943, an air armada of 177 4‑engine B‑24s Liberators lifted off Libyan airstrips to bomb Romania’s Ploesti oil complex, the Wehrmacht’s “taproot of German might,” said British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. German and Romanian fighter aircraft and flak batteries shot down 54 planes, each with 10 or 12 crewmen. Another 53 planes were heavily damaged, most beyond repair. On their return flight many other aircraft were lost over land and sea. Though Allied reconnaissance flights confirmed that damage to the Ploesti complex was significant, it was a hollow victory. Allied bombers continued hitting Ploesti over and over again until August 19, 1944, a week and a half before Soviet soldiers captured the oil complex.

![]()

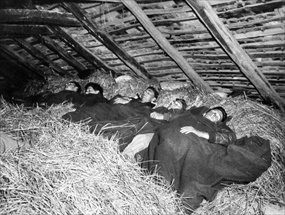

Right: Hiding from German patrols while awaiting air rescue via Operation Halyard, a group of weary U.S. flyboys get some sleep in a hayloft somewhere in Yugoslavia. A cooperative OSS-Chetnik effort to get downed airmen out of Nazi-occupied territory, Operation Halyard was a remarkable success.

|  |

Left: At an airfield in Yugoslavia airmen load a wounded man into a C‑47 for transport to Italy, a 2‑hour flight away. (C‑47s were the military version of the DC‑3 passenger plane.) During the course of their rescue operations, the OSS and Chetnik soldiers successfully returned over 500 downed airmen from Nazi-controlled territory in Yugoslavia to Allied bases.

![]()

Right: Smiling in anticipation of their return to Allied territory, a group of downed airmen sit on hard metal seats aboard a C‑47 transport plane. This photo was taken during a flight from an airstrip at Koceljeva, Northwestern Serbia, on September 17, 1944, when 17 airmen were flown to safety. President Harry S. Truman, on the recommendation of Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, former supreme commander of Allied forces in Europe (December 1943 to November 1945), posthumously awarded Mihailović the Legion of Merit Chief Commander—the highest military award conferred on a foreign national for service to the country—for the rescue of U.S. and other Allied airmen by the Chetniks. “General Dragoljub Mihailovich,” the citation dated March 29, 1948, read “distinguished himself in an outstanding manner as Commander-in-Chief of the Yugoslavian Army Forces and later as Minister of War by organizing and leading important resistance forces against the enemy which occupied Yugoslavia from December 1941 to December 1944. Through the undaunted efforts of his troops, many United States airmen were rescued and returned safely to friendly control. General Mihailovich and his forces, although lacking adequate supplies, and fighting under extreme hardships, contributed materially to the Allied cause and were instrumental in obtaining a final Allied victory.” The award and the story of the airmen’s rescue were classified secret by the U.S. State Department so as not to offend the Yugoslav government of President Tito (in office 1945–1980). The secret was revealed to the world in 1967.

Operation Halyard: The Greatest Rescue Mission of U.S. Airmen Behind Enemy Lines in History

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click