GROUND BROKEN FOR TULE LAKE RELOCATION CENTER

Tulelake, Modoc County, California • April 15, 1942

On this date in 1942, in a remote, underdeveloped reclamation district roughly 35 miles/56 kilometers southeast of Klamath Falls, Oregon, and about 10 miles/16 kilometers from the town of Tulelake (or Newell), the federal government began construction of the Tule Lake Relocation Center for persons of Japanese ancestry forcibly deported from the U.S. West Coast. Shortly thereafter the first Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans departed their hastily erected assembly centers (actually transit camps) in Portland, Oregon, and Puyallup, Washington and arrived to help set up the new relocation center. In the weeks ahead similar assembly centers in California’s Maryville, Pinedale, Pomona, Sacramento, and Salinas emptied their evacuees, as internees or incarcerees of Japanese descent were then known, into the Tule Lake Relocation Center; a number were sent directly to Tule Lake from cities in the southern San Joaquin Valley, the large agricultural valley running down the center of the state.

The banishment of Japanese nationals (Issei) and U.S.-born Japanese Americans (Nisei and Sansei, second- and third-generation Japanese, respectively) to remote corners of the country regardless of age was based not on what these people had done or ever would do to put the nation’s security at risk but on who they were: members of a race in Asia with whom the United States was at war. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s February 19, 1942, Executive Order 9066 (it really was FDR’s to own, as most of the president’s advisers had not argued for anything so tragically encompassing) swept up two-thirds of the country’s Japanese “non-aliens” (the wartime term for Nisei and Sansei) plus the remaining Issei residing in California, western Oregon and Washington, and southern Arizona, the so-called “Exclusion Area” officially known as Military Areas 1 and 2. So Tule Lake, along with 9 other permanent camps managed by the civilian-run War Relocation Authority (WRA), was used to intern “for the duration” (a conveniently vague span of time) close to a tenth of the almost 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry who might conceivably pose a danger.

In early 1943 the War Department, in an effort to recruit volunteers from WRA camps for an all-Nisei combat unit, created an ill-conceived questionnaire for internees 17 and older to determine their “loyalty.” Two questions, one concerning potential service in the U.S. armed forces (Question 27), the other (Question 28) concerning forswearing allegiance to Japan and swearing unqualified allegiance to the U.S. (while locked up, no less!), caused much anxiety and agonizing. What if individual family members answered differently? Would members be separated? Particularly Issei, who by law were barred from becoming naturalized Americans, feared answering “Yes” to the second question. Might they become stateless persons? Many internees (42 percent at Tule Lake) were so upset and insulted by the 2 questions that they answered “No-No” to both or point-blank resisted filling out the compulsory questionnaire.

Because the largest proportion of internees whom the government now considered “disloyal” was at Tule Lake, the WRA converted the camp into a maximum security segregation facility. By the fall of 1943, 6,500 “loyal” Tuleans who had answered “Yes-Yes” were transferred to other camps, and about 12,000 “No-Nos” (so-called “recalcitrants”) and resisters (“incorrigible agitators”) with their families arrived from the other 9 WRA camps. The newcomers joined 6,000 Tulean “No-Nos,” resisters, and “loyals” (4,000) who chose to stay. A camp built for 10,000 now had to accommodate 18,700 internees—prisoners who were watched over by the largest, most substantial military police presence (1,200 soldiers equipped with 8 tanks) of any WRA camp.

World War II Japanese Internment: The Example of Tule Lake Relocation/Segregation Center

|

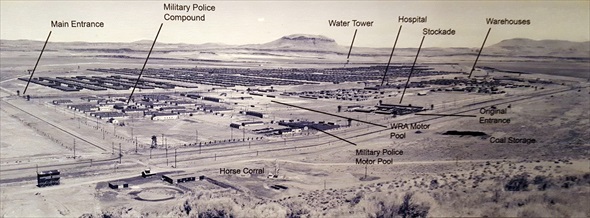

Above: Run by the War Relocation Authority, a U.S. civilian agency, Tule Lake Relocation Center (from August 1943, Tule Lake Segregation Center) encompassed 7,400 acres/2,995 hectares of which 3,500 acres/1,416 hectares of the former lake bed were under cultivation in 1941. At an elevation of 4,000 feet/1,219 meters, the high-desert summers were hot and dusty, the winters long and cold. Natural vegetation consisted of sparse grass, tules (bulrushes), and sagebrush. No trees. Several tens of thousands of people of Japanese heritage passed through Tule Lake until it closed on March 20, 1946, the last (at one point, the largest and arguably the most controversial) of the 10 WRA camps to shut down. The entire Japanese American detention and relocation program was justified at the time as a “military necessity.” Forty years later the U.S. government conceded that the program was based on racial bias rather than on any real threat to the nation’s security.

|  |

Left: Construction of primitive, thin-walled wood and tar paper-covered barrack “apartments” has begun at Tule Lake for internees of Japanese ancestry. Upon completion there were 74 residential blocks, each accommodating approximately 260 people. Each block consisted of 13 20‑ft x 100‑ft/6‑m x 30‑m barracks divided into 4-to-6 small single-family rooms that took no account of family size. Each drab apartment was furnished with hard army cots, an oil-fired heater to heat the space, and one naked light bulb screwed into a ceramic socket on the end of a long cord hanging from a rafter. The triangular-shaped opening above the apartments formed by the rafters and the roof—there were no ceilings—allowed voices and noise to carry throughout the barrack. Photo by Clem Albers, April 23, 1942. Albers was 1 of 3 photographers in the WRA Photography Section, or WRAPS, in 1942–1943. The other two were Francis Stewart and Dorothea Lange.

![]()

Right: These displaced Japanese board a Tule Lake-bound train accompanied by only what they could carry in their two hands. Larger personal items identified by family name and destination would be placed in baggage cars and unloaded at a siding inside the relocation center’s barbed wire perimeter. Photographer and date unknown.

|  |

Left: Scene in the fingerprinting department at the Tule Lake induction center as an elderly woman has impressions made of her fingers on both hands. All Tule Lake internees were compelled to be fingerprinted and photographed. Photographer Charles Mace, September 25, 1943.

![]()

Right: Having just arrived at Tule Lake, these internees are being assigned housing and bedding by staff in 1 of the 4 interconnected administration buildings. Photographer Francis Stewart, July 1, 1942.

|  |

Left: The interior of General Store No. 2 at Tule Lake. Photographer Francis Stewart, July 1, 1942. Tule Lake internees had the services of a large hospital (19 barracks), a post office, a Bank of America (open 2 days a week), men’s and women’s hair salons, a newsstand where the center’s bilingual Tulean Dispatch was sold, a funeral parlor and cemetery, and communal mess halls cum assembly halls, one per residential block (14 barracks). A large stockade with 12‑ft/3.6‑m-high wooden walls and an adjacent steel-reinforced concrete jail built to hold 24 persons (at one time it held 100) were part of the bleak camp-scape. WPA-run nursery, elementary, and secondary schools (always short of qualified staff), baseball and softball fields, judo halls, a sumo wrestling pit, and Christian and Buddhist churches were further attempts by the WRA and by the internees using their own meager funds to duplicate academic institutions, social and recreational opportunities, and spiritual life outside the 3½‑ft/3.1‑m-high warning fence and the guarded and lighted 6‑ft/1.8‑m-high “man-proof” perimeter security fence of chain link and barbed wire.

![]()

Right: This Associated Press photograph, dated May 21, 1943, appeared in national news media with the following caption: “Young Japanese Hold Dance—Mess hall movies, little theatre activities and jitter-bugging to evacuee bands are popular forms of entertainment at the Tule Lake, California, Japanese relocation center. Here a block dance is in progress. Note the ‘zoot suit’ pants.”

|  |

Left: Riding light tractors a crew of internee farmers plant potatoes using semi-automatic-feeding, rotary potato planters on several hundred acres of fertile soil reclaimed from old Tule Lake. Associated Press photograph, May 21, 1943.

![]()

Right: Harvesting spinach. Tule Lake internees grew other crops: the aforementioned potatoes, also wheat, oats, rye, barley, onions, carrots, turnips, rutabagas, lettuce, Chinese cabbage, and celery. Hogs, chickens, and turkeys were raised and butchered. Carp was caught in irrigation canals. Nevertheless, mess hall menus leaned heavily on carbohydrates. Excess foodstuffs were shipped to other WRA relocation centers. Photographer Francis Stewart, September 8, 1942.

War Relocation Authority Wartime Propaganda Film: “A Challenge to Democracy,” a View Inside U.S. Japanese Internment Camps

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click