GERMANY, ITALY DECLARE WAR ON U.S.

Berlin, Germany • December 11, 1941

On this date in 1941 in Berlin, Adolf Hitler, Chancellor and Fuehrer of Nazi Germany, addressed a toothless Reichstag (German parliament), its members eager to hear him declare war on America. Hitler did this four days after air and naval units of the Imperial Japanese Navy had ambushed the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Technically speaking, Germany was not forced or even obligated by its September 27, 1940, treaty with Japan to do so. (A hurriedly amended treaty with Japan containing the key clause ruling out an armistice with the U.S. or Britain without mutual consent, even if Japan was the aggressor nation, was signed minutes before Hitler’s speech to the Reichstag.)

Hitler expressed surprise and initial incredulity when he learned of the attack on Pearl Harbor, though he long expected that Japan would be forced to act against the United States if it was serious about claiming world-power status. Pressured by the Japanese military attaché and ambassador in Berlin, Baron Hiroshi Ōshima, to declare war on the U.S. sooner than later, Hitler’s gesture of solidarity with a country halfway around the world seemed absurd, risky, and unnecessary on the surface—this at a time when the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) was on the verge of needing even more martial resources to fend off a dangerous counteroffensive by the Soviet Army in what promised to become a protracted war in the East. But the declaration of war, Hitler told his foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, the “politically correct” thing to do. (Hitler’s statement to Ribbentrop may have been a reference to his foreign minister having given oral assurances to his personal friend Ōshima some two weeks earlier that the Third Reich would join the Japanese government in case of war against the United States.)

An added benefit to the U.S.-Japanese war, Hitler told his propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, was that the U.S. would be less likely to provide aircraft and weapons and convoy support and ships to the British, with whom Germany had been at war since September 1939, because “it can be presumed that they will need all that for their own war with Japan.” U.S. Navy ships that had been shooting at German surface ships and submarines during the Battle of the Atlantic for months now might find choicer targets in the Pacific Ocean in the post-Pearl Harbor context. Goebbels couldn’t be happier: “The Asian conflict drops like a present into our lap.”

At this point in time, though, the Luftwaffe’s air battle against Great Britain was lost, the blitzkrieg on Germany’s Eastern Front (Operation Barbarossa) had failed with a loss of over 750,000 men to the participating Axis powers, and the Italian venture in North Africa by Hitler’s Axis partner Benito Mussolini needed all the support Gen. Erwin Rommel’s German Afrika Korps could provide. (A surprisingly rosy war prognosis from the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht on December 14, 1941, forecast a Germany victory on the Eastern Front, that neutral nations like Sweden, Spain, Portugal, and Turkey would join the Axis alliance, and that Japan’s war against the West in the Pacific would militate against the United States successfully waging two separate wars.) Now, on December 11, 1941, before insanely cheering deputies of the sham Reichstag Hitler screamed insults, often bizarre ones, at his new enemy, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “that man who, while our soldiers are fighting in snow and ice . . . likes to make his chats from the fireside, the man who is the main culprit in this war.” No doubt British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was as surprised as Roosevelt was that the Fuehrer’s favorite bête noire had shifted from the stubborn British bulldog to the determined American eagle.

![]()

Germany and the U.S. Declare War on Each Other, December 11, 1941

|

Above: Headlines in the late edition of The New York Times, December 11, 1941. Earlier in the day the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives passed a unanimous declaration of war on Germany and Italy, only hours after Hitler had declared war on the U.S and three days after Congress had declared war on Japan.

|  |

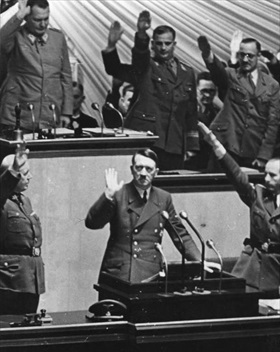

Left: Hitler receiving the endorsement of the Reichstag on December 11, 1941, after declaring war on the United States. Full of optimism and confident of victory, Hitler told his Reichstag audience, which included Japanese ambassador Hiroshi Ōshima, that Germany, Italy, and Japan had concluded an agreement to “wage the common war forced upon them by the U.S.A. and England with all the means of power at their disposal, to a victorious conclusion [and pledged] . . . not to conclude an armistice or peace with the U.S.A. or with England without complete mutual understanding.” Less than four years later both Germany and Japan were compelled by their enemies to sign separate unconditional surrenders on May 7–8 (Germany) and September 2 (Japan), 1945.

![]()

Right: President Roosevelt signing the declaration of war against Germany, December 11, 1941. Texas Senator Tom Connally stands to the left of the president, holding a pocket watch to fix the exact time of the signing—3:05 p.m. EST. One minute later Roosevelt signed the declaration of war against Italy. In so doing the U.S. joined a global war that threatened the survival of peoples and nations in Europe, North Africa, and the Far East. Six months later, on June 5, 1942, Congress declared war on Germany’s and Italy’s Axis partners, Romania, Hungary, and Bulgaria. Not until February 10, 1947, were peace treaties concluded between the victorious Allies and Italy, Finland, and the Soviet Union’s East European satellite countries of Romania, Hungary, and Bulgaria.

Adolf Hitler Declares War on the United States and the Lead-Up to World War II

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click