GERMANS TRY PUSHING ALLIES OFF ANZIO BEACHHEAD

Anzio, Italy • February 16, 1944

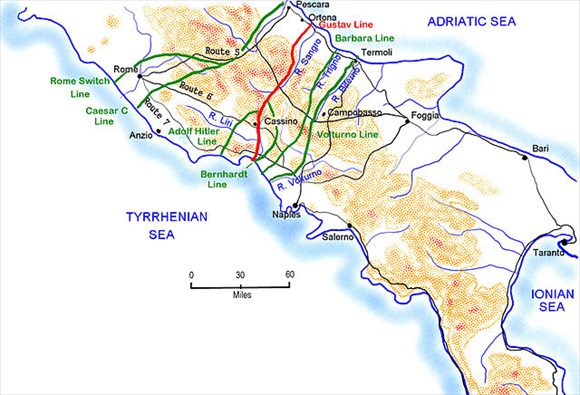

On this date in 1944, a day after the historic Benedictine abbey at Monte Cassino was bombed by Allied aircraft, the Germans launched their long-delayed counterattack on the Allied-held beachhead at Anzio, a small Mediterranean resort and port some 35 miles/56 kilometers south of the Italian capital, Rome. Just the month before, on January 22, American and British units under U.S. Maj. Gen. John Lucas had carried out an essentially unopposed amphibious landing in the area of Anzio and neighboring Nettuno, Italy. By the end of first day of Operation Shingle, 36,000 Allied soldiers and 3,200 vehicles had stormed ashore, captured the port of Anzio, and were poised to outflank strong German defenses along the Gustav Line centered on Cassino south of Anzio (see map below)—defenses that were holding up the Allies’ liberation of Rome. A jeep reconnaissance patrol had even made it as far north as Rome’s outskirts. Tragically Lucas, who heeded the advice of his commander, Lt. Gen. Mark Clark, not to “stick his neck out,” never exploited his advantage of surprise, delaying his advance until he judged his position sufficiently consolidated and his troops ready.

The German commander in the Italian theater, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, one of the ablest generals in the Nazi Wehrmacht (armed forces), moved artillery and every spare unit to be found into a ring around the Allies’ narrow beachhead, a reclaimed marshland 15 miles/24 kilometers long and 7 miles/11 kilometers deep kept dry by giant pumps. (Kesselring ordered the pumps turned off, flooding the Allies’ beachhead.) By early February Kesselring had roughly 100,000 troops poised against Allied forces, which by this time totaled a little more than 76,000. German infantrymen and tanks, by launching Operation Fischfang (Operation Fish Trap) on February 16, shrank the American pocket over the next 5 days to within 6 miles/13 kilometers of the shoreline before reaching a vicious stalemate with their foe. (Luckily for the Allies, these German units had run out of oomph, having fought themselves to a standstill.) Both combatants lost nearly 20,000 men each since the January landings.

Aside from Lucas being relieved of his command a month later and sent home (on the grounds of ill health; his replacement was Maj. Gen. Lucian Truscott), the Allies’ tactical situation would not change until late May, when the northward moving U.S. Fifth Army’s front under Mark Clark merged with the Anzio beachhead. The road to the Italian capital was now wide open, and Clark took full advantage of it, surprising his commanding officer, British Gen. Harold Alexander, and even Romans themselves when he triumphantly entered the capital riding in an open jeep on June 5, 1944, 1 day before Allied landings on the Normandy coast in France abruptly yanked the world’s attention from Italy to Northwestern Europe.

The Italian Campaign, January–June 1944

|

Above: German-prepared defensive lines in Italy south of Rome, 1943–1944. The primary line was the heavily defended Gustav Line (red in map) centered on the town of Cassino, which interdicted traffic north on Route 6. Operation Shingle, the Anzio offensive (January 22 to June 5, 1944), was designed to outflank the Gustav Line defenders, capture Rome by moving up the coast along Route 7, the 2,000-year-old Via Appia (Appian Way), and in the process of pushing inland either cut off German forces in Southern Italy, leaving them to die on the vine, or annihilate them.

|  |

Left: Anzio, a coastal town on the Tyrrhenian Sea, was the site of a major amphibious assault by the U.S. VI Corps, U.S. Fifth Army, in late-January 1944. The Anzio offensive had been championed by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, but it fell largely to American troops to carry it out. Landing 2 Allied divisions behind enemy lines was intended to force the Germans to evacuate the Italian peninsula and, it was hoped, shorten the war. For their part Field Marshal Kesselring and the German army units under his command refused to play their Allied-assigned role and, with the arrival of reinforcements, nearly wiped out the Allied troops pinned down on the Anzio beachhead.

![]()

Right: German paratroopers with artillery piece in the vicinity of Nettuno (near Anzio), Italy. Gunners like these in the Alban Hills had a clear view of every Allied position on the Anzio beachhead 4 miles/6.4 km away. The Battle of Anzio lasted four months, the Allied side being supplied by sea, the German side by land through Rome. In May 1944 the Allies broke free of the Anzio deathtrap and took Rome. German forces escaped to regroup north of Florence at the Gothic Line.

|  |

Left: Captured German soldiers on the Anzio beachhead are being moved to an Allied prison camp, February 1944. The Germans and Italians suffered 40,000 casualties, of which 5,000 were war dead. The Allies took 4,500 prisoners.

![]()

Right: British and American prisoners of war move their wounded comrades to a German aid station near Nettuno, February 1944. The Allies suffered 43,000 casualties, of which 7,000 were killed. Analysts of the Anzio offensive have criticized the campaign for its large number of dead, wounded, and missing and its shoddy execution, notwithstanding that the Allies’ ultimate goal, the liberation of Rome, was achieved.

U.S. Fifth Army Report from the Anzio Beachhead, Operation Shingle, February 1944

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click