GERMANS, SOVIETS AGREE TO HISTORIC NONAGGRESSION PACT

Moscow, Soviet Union • August 23, 1939

At least since April 1939 Adolf Hitler was determined to end the existence of Poland, a country of just over 35 million people lying on Germany’s eastern border. But conquering that nation was fraught with danger because Poland shared a border with the Soviet Union, Hitler’s long-time bogeyman. The Fuehrer and his propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels had spent their careers denouncing the “Jewish-Bolshevik” regime in Moscow, going to far as to create an anti-Soviet alliance, the Anti-Comintern Pact, in the mid-Thirties, which eventually grew to over a dozen states in Europe and Asia (Japan and its vassal states on the Chinese mainland). Now what to do should Nazi Germany wish to neutralize the prospect of the Soviet Union being threatened by Germany’s destruction of its western neighbor?

It began that April 1939 when Hitler and the German news media suddenly ceased their anti-Soviet rhetoric. In May the German ambassador to the Kremlin was instructed to put out feelers for a possible German-Soviet political rapprochement. Earlier that month Joseph Stalin had dismissed his pro-Western Jewish foreign minister and replaced him with a long-time loyalist, Vyacheslav Molotov, in the process removing what the Nazis saw as an impediment to improving relations. The scene brightened further when, at the start of August, German and Soviet trade officials agreed that the interests of the 2 antagonistic nations could and should be harmonized. A comprehensive trade deal was struck in the early hours of August 20: Germany would gain access to Soviet agricultural produce and oil, and in return the Soviet Union would have access to modern machinery and military equipment. Convinced that Hitler was serious about improving bilateral relations, Stalin agreed to receive German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop in Moscow to entertain a second historic agreement.

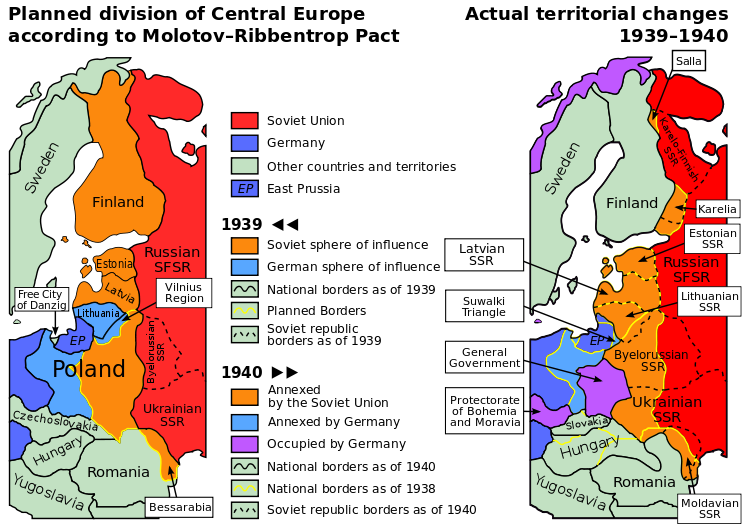

That agreement was the Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Pact drafted late on this date, August 23, 1939, by the countries’ foreign ministers and signed in the early hours of the 24th. The 10‑year pact assured that the 2 rivals would henceforth “desist from any act of violence, any aggressive action, and any attack on each other.” In truth, though, the short, 7‑article nonaggression pact was window dressing for a secret protocol to rearrange the “territorial and political” integrity of states lying between them, from Finland in the north, through the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) and Poland, to Romania in the south (see map below). The pact removed a nightmare shared by Hitler and the operations staff of his Wehrmacht (armed forces). Hitler could swoop down on Poland as he’d long intended absent now the threat of Soviet pushback, and Stalin was liberated by the demise of the Anti-Comintern Pact, which both their foreign ministers had eviscerated by initialing the secret protocol.

Poland was doomed, notwithstanding an Anglo-Polish military pact—the Agreement of Mutual Assistance between the United Kingdom and Poland—entered into on August 26, 1939. The mutual assistance agreement was a British pledge to provide military aid to Poland were it attacked by Germany. The Nazi-Soviet and Anglo-Polish pacts, signed within days of each other, predictably set in motion the engines of a European war, which started on September 1, 1939, when Germany invaded Poland from the east, and on September 17, when the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the west.

Molotov-Ribbentrop Nonaggression Pact, August 23, 1939

|  |

Left: On August 24, 1939, Soviet newspapers carried accounts of the non-secret portions of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Nonaggression Pact, including a front-page picture of Molotov signing the treaty as Ribbentrop and Stalin, all smiles, looked on. The news reports were met with widespread incredulity by Western governments and media, as well as by people inside Germany and the Soviet Union. Hadn’t the countries been sworn enemies? In Asia, Japan’s cabinet resigned over Hitler’s cozying up to that country’s longtime enemy in the midst of a fierce border war taking place in the steppes of Mongolia (Khalkhyn Gol/Nomonhan Incident, May 11 to September 15, 1939), which resulted in a Soviet-Mongolian victory over Japanese expansionists.

![]()

Right: Molotov would live to regret his part in the Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Pact. Almost 22 months later, on June 22, 1941, Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, intending to utterly destroy his treaty partner in the largest land invasion in history: sweeping across a 1,000‑mile/1,609 km front, 3 million Germans were hell-bent on annihilating the Red Army and capturing the country’s principle cities and oil fields west of the Ural Mountains. It came close to happening.

|

Above: The left panel in this map of Central Europe depicts the planned division of the region according to the August 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Nonaggression Pact. Yellow lines represent the planned borders. The Soviet Union and the Soviet spheres of influence are in red and tan, respectively. Germany and the German sphere of influence are in shades of blue. The right panel depicts the actual 1939–1940 territorial changes. Yellow lines represent the 1938 borders. The dashed black lines represent the borders of the enlarged Soviet states (SSR=Soviet Socialist Republic) in 1940. German annexations are shown in light blue. Purple depicts German-occupied territories and states: Norway, the General Government in Central Poland, and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in Western Czechoslovakia.

British Historian Roger Moorhouse on the Impact of Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and Its Secret Protocols

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click