GERMANS PREPARE ARDENNES OFFENSIVE

Cologne, Germany · November 15, 1944

As the Allied offensive ground on west of the Rhine River, dozens of German tank and infantry divisions gathered in assembly areas northwest of the city of Cologne and in the thick forest cover of the Eifel Mountains on this date in 1944. Conceived by Adolf Hitler, the plan, codenamed Wacht am Rhein (Operation Watch on the Rhine), was to attack through the weakly held American lines in the Ardennes Forest in Luxembourg, recapture the strategic deep-water Belgian port of Antwerp, sever Allied supply lines, split Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery’s army in Northern Belgium and Holland from Gen. Omar Bradley’s armies to the south, and force the Western Allies, separate from the Soviet Union, to negotiate a peace treaty in Germany’s favor. Once that was accomplished, Germany could buy time to design and produce more advanced weapons (for example, the Messerschmitt Me 262 jet aircraft and the Panzerkampfwagen E‑100 super-heavy tank) and fully concentrate its attention on its Eastern Front, which under withering Soviet one-two hammer blows would soon shift nearly as far west as East Prussia.

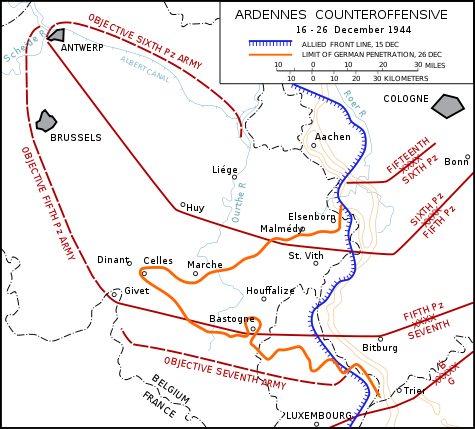

Warning signs of a pending German offensive had been ignored when, on December 16, 1944, in a carefully coordinated attack, more than 300,000 Germans launched what became known as the Battle of the Bulge, or the Ardennes Offensive. Fierce resistance on the northern shoulder of the offensive around Elsenborn Ridge and in the south around Bastogne (see map below) blocked German access to key roads to the northwest and west that the enemy had counted on for success. The acting commander of the trapped 101st Airborne Division, Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, famously replied “Nuts” to the German demand of December 22 to surrender the crossroads town of Bastogne.

The day after Christmas Bastogne was relieved when elements of Gen. George Patton’s U.S. Third Army burst through German lines. Eventually more than a million GIs were thrown into the battle, and by mid-January 1945 Hitler’s last-ditch gambit had collapsed, the German military high command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht) accepting that the Western Front was lost. Hitler, who had arrived in a long motorcade of black Mercedes at his western headquarters at Adlerhorst (“Eagle’s Eyrie”) in the German state of Hessen on December 11, 1944, left by train for his subterranean Fuehrerbunker in Berlin on January 16, 1945, where he met his end, a suicide, 3½ months later. German losses in the failed western offensive ranged from 60,000 to 100,000 men (half of them prisoners) and more than 600 tanks and heavy assault guns. Official Allied casualties ranged from 90,000 to over 100,000. The Battle of the Bulge/Ardennes Offensive (December 16, 1944, to January 25, 1945) was the greatest single extended land battle as well as the bloodiest that U.S. forces experienced in World War II—19,000 dead, nearly 50,000 wounded, and over 4,000 taken prisoner. Its net effect, however, was to delay the Allied conquest of Germany by just 6 weeks.

The Ardennes Campaign and the German “Bulge,” December 1944

|

Above: The German Army launched a surprise attack in Belgium and Luxembourg in December 1944 in an attempt to reach the Belgian port of Antwerp and the North Sea and thus drive a wedge between the British and American forces in Northern France. The army drew on every available resource it had left—300,000 men, 970 tanks and assault guns, and 1,900 artillery pieces. This map shows the extent of the German counteroffensive that created the so-called “bulge” in Allied lines between December 16 and 26, 1944. The original German objectives are outlined in red dashed lines. The orange line indicates the Germans’ furthest advance westward. The German advance was stopped at the Meuse River at Dinant, shown just west of the orange bulge.

|  |

Left: A German regiment in the bitterly cold Ardennes Forest, December 1944. Hitler selected the Ardennes for his western counteroffensive for several reasons: the terrain to the east of the Ardennes and northwest of Cologne was heavily wooded and offered cover against Allied air observation and attack during the build-up of German troops and supplies; the rugged Ardennes wedge itself required relatively few German divisions; and a speedy attack to regain the initiative in this particular area would erase the Western Allies’ ground threat to Germany’s industrialized Ruhr centered around Duesseldorf and delay their advance on Berlin.

![]()

Right: German troops advance past abandoned American equipment. The Western Allies’ string of dazzling successes in 1944, news reports of the bloody defeats that the Soviet armies were administering to the Germans on the Eastern Front, and the belief that the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) was collapsing and the Third Reich was tottering on its knees led Allied war planners to pay scant attention to the quiet Ardennes sector. The Americans especially paid dearly for this mindset, as well as for ignoring their own intelligence of the Ardennes counteroffensive preparations.

|  |

Left: German field commanders plan their advance through Luxembourg’s Ardennes Forest. In the Battle of Elsenborn Ridge, which lasted 10 days, the American and German lines were often confused. The main drive against Elsenborn Ridge was launched in the forests east of the twin villages of Rocherath-Krinkelt early in the morning of December 17, 1944. This attack was begun by tank and Panzergrenadiers (mechanized infantry) of the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend. By December 27, the Germans had beaten themselves into a state of uselessness against the heavily fortified American position.

![]()

Right: Captured teenage youth from the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend. Units of Gen. Leonard T. Gerow’s V Corps of the U.S. First Army held Elsenborn Ridge against the elite SS division, preventing it and attached forces from reaching the vast array of supplies near the cities of Liège and Spa in Belgium, as well as the road network west of the ridge leading to the Meuse River and the city of Antwerp. This was the only sector of the American front line during the Battle of the Bulge where the Germans failed to advance.

Contemporary U.S. Army Film of the Battle of the Bulge

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click