GERMANS FACE CALAMITY AT KURSK

Kursk, Soviet Union · July 13, 1943

On this date in 1943 Operation Citadel (Zitadelle), Adolf Hitler’s gambit to retake the important Soviet rail hub of Kursk, south of Moscow, and straighten the German line on the Eastern Front failed with devastating losses on both sides, but especially to German strategic armored reserves. A day earlier a gigantic clash of arms approaching mythic status—upwards of 6,000 tanks, 4,000 airplanes, and two million men—ended in a draw near the village of Prokhorovka.

Nevertheless, the eleven-day Battle of Kursk was evidence that German fortunes were shifting toward the Soviet Union in that country’s Great Patriotic War. In the course of three major engagements between July 4 and August 23, 1943, the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) suffered over 200,000 casualties and lost an estimated 760 tanks and assault guns and more than 680 aircraft. Soviet losses were many times higher for the same period; for example, over 863,000 casualties alone. But the Wehrmacht had grown powerless to stanch or keep pace with the steady influx of Red Army soldiers (some drafted from retaken territories) and new materiel arriving on the Eastern Front, much of the equipment provided by Allied Arctic convoys and overland shipments through Iran.

Furthermore, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin’s long-standing call for a second front materialized three days earlier, on July 10, 1943. The Anglo-American landings in Sicily (Operation Husky) engaged more troops than were involved in the Normandy landings eleven months later (Operation Overlord). The Sicily landings were followed by those on the Italian mainland in September (Operations Avalanche, Baytown, and Slapstick). Taken together, events in the Mediterranean Theater forced Hitler to redeploy forces from the Eastern to the Italian Front. From the conclusion of the Kursk clash of men and armor to the end of the war in Europe less than two years later, Stalin’s armies advanced relentlessly westward across a broad front. In a series of vicious hammer blows, the Soviets decimated Hitler’s Army Group Center in Belarus (Operation Bagration), annihilated Army Group South in the Ukraine, and inflicted crushing casualties while knocking Axis partners Romania and Hungary out of the war. (In early 1943, after Stalingrad, Hitler’s comrade-in-arms, Benito Mussolini, withdrew his armed forces from the East.) By February 1945 both Hitler’s Wehrmacht and his Thousand-Year Reich lay at death’s door.

The Wehrmacht Retreats: Fighting a Lost War, 1943–1945

|

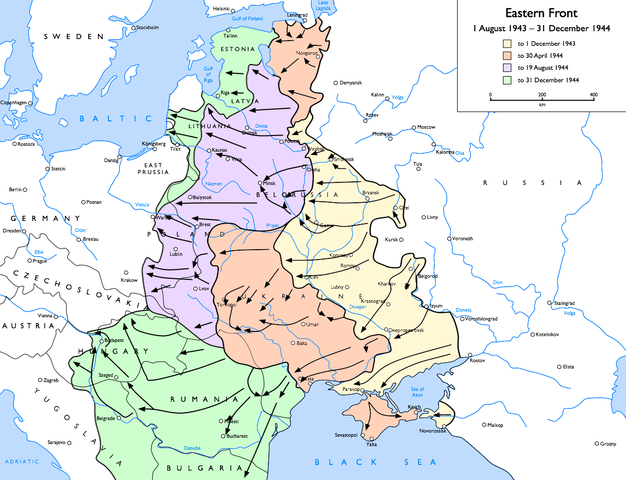

Above: Soviet advances on the Eastern Front, August 1943 to December 1944. The Kursk salient in Russia is the white bulge half the size of England, 150 miles long and 100 miles wide, in the tan area of the colored portion of the map. The Soviets looked upon the salient as the springboard for the reconquest of territories and population centers (Orel and Bryansk) to the northwest and, to the southwest, the fertile farmlands of the Ukraine, with its capital of Kiev, the third largest city in the Soviet Union. Red Army defenders were delighted that the Germans had chosen to target the Kursk sector, where since March huge concentrations of Soviet troops, armor, and artillery (the Red Army’s proclaimed “god of war”) had been amassed, in some places stretching as deep as 65 miles from the front lines. (Soviet superiority in the Kursk sector was 3:1 in manpower and 1.5:1 in armor.) On July 13, 1943, Hitler aborted Operation Citadel, having failed to put more than a couple of dents in the Kursk bulge. It proved to be the turning point in the war in the east. Over the next months the Wehrmacht, attrited of men, machines, equipment, and interdicting aircraft, was repeatedly rolled up by Red Army operational and strategic reserves after first being mauled, ground down, and dislocated by powerful Soviet formations along a very broad front.

|  |

Left: Soviet armor advances to engage the enemy during the Battle of Kursk, July 5 to 16, 1943. The combined Voronezh and Steppe Soviet fronts deployed about 2,418 tanks and 1,144,000 men. Red Army personnel losses amounted to at least 177,000, with combat losses between 20 and 70 percent of the units committed. Soviet tank and self-propelled assault gun losses amounted to 1,614 vehicles irreparably destroyed. After heavy fighting lasting 10 days, Soviet striking power had not appreciably diminished. In fact, it seemed to German observers to have increased. German Army Group Center and Army Group South—the two army groups at Kursk—lost 323 tanks and assault guns irreparably destroyed. Personnel losses amounted to 50,000 men killed, wounded, or missing.

![]()

Right: A Waffen-SS Mark VI Tiger I heavy tank scores a direct hit on a Soviet T‑34 medium tank during the German offensive at Kursk. The quality of advanced optical sights on the Tiger I and the high-velocity 88mm gun it mounted allowed it to devastate targets at long range with great accuracy. Hitler postponed Operation Citadel for two months in part to give German armament manufacturers time to rush to the Eastern Front new Tiger I heavy tanks and Mark V Panther medium tanks, both considered superior to tanks of equivalent class the Soviets possessed. The delay gave the Red Army time to roll half a million railcars into the Kursk salient, pouring in division after division, tank after tank, artillery piece after artillery piece. More than 300,000 civilians, mostly women and old men, helped Soviet soldiers dig trenches and build fortifications. The southern shoulder of the salient alone boasted 2,600 miles of trenches and mine densities of 5,000 per mile of front, laid out to channel German panzers into the crossfire of antitank strongholds. By July 1943 Kursk became the strongest fortress in the world. German morale was high at the start of the conflict because they had little idea what they faced.

|  |

Left: Three Soviet Ilyushin IL-2 Sturmovik ground-attack aircraft assault enemy troops in the southern sector (Voronezh Front) of the Kursk salient, July 1943. The Soviet offensive lasted from July 12 to August 23, 1943. Some 36,183 of these superb two-seater, single-engine, armor-plated monoplanes were produced during the war, mostly to the east of the Ural Mountains away from the Luftwaffe’s long reach. Nicknamed “The Flying Tank” by intimidated German ground troops, the IL‑2 was armed with two 23mm cannons, two machine guns, and loaded with up to 1,300 lb of bombs and 12 rockets. The warplane also could be fitted with small-caliber (3.3 lb) bomblets in its bomb bay that, when dropped in a carpet of bombs, could decimate entire enemy columns and also “kill” thick-armored Panther Mark V and Tiger I German tanks. In a mass attack on July 7, 1943, IL‑2s were credited with destroying 70 German tanks in 20 minutes. A prototype of the Ilyushin IL‑2 first flew in October 1940, and Red Army units began receiving deliveries in May 1941. In combination with its faster, more maneuverable successor, the Ilyushin IL‑10 introduced in 1944, a total of 42,330 Ilyushins were built, making it the single most-produced military aircraft design in aviation history.

![]()

Right: Soviet antitank riflemen take aim at an enemy tank after the Battle of Kursk had wound down, July 20, 1943. The 11‑day German offensive at Kursk was the first time a Blitzkrieg (“lightning war”) had been blunted before it could break through enemy defenses and into its strategic depths. Kursk was the Soviets’ critical contribution to winning the war against Hitler and his Third Reich.

Turning the Tables on Nazi Germany: The Battle of Kursk, July 1943

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click