GERMAN NAVY HEAD DOENITZ FLEES BERLIN

Ploen, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany • April 22, 1945

By the start of April 1945 most large German cities were rubbish heaps. Cityscapes were characterized by great rows of apartment blocks with their brick or stone facades ripped open. Church spires and factory chimneys poked into grimy skies, their walls and roofs collapsed. These scenes of civilian and industrial wastelands were the results of “totaler Krieg” (total war), though certainly not in the sense that Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels had urged Germans to embrace some 2 years earlier. The hoisted petard of Nazi vengeance that was intended to gravely or mortally wound Germany’s enemies instead wreaked horrendous damage on the nation itself.

On April 15, 1945, anticipating a Red Army offensive on his capital Berlin and excruciatingly aware that the rapid Allied advances had pretty much bisected the country on an east-west axis, Adolf Hitler split the civil and supreme military command of his ever-shrinking Third Reich between Commander-in-Chief West (Oberbefehlshaber West) Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, pulling duty in Southern Germany, and Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz, since 1943 gifted head of the Kriegsmarine (German navy), assuming duty in the country’s northern sector. A week later, on this date, April 22, 1945, Doenitz moved Naval High Command headquarters from Berlin to the small northern town of Ploen in Schleswig-Holstein, ordering thousands of naval personnel to take up arms in support of old men and boys and the sick and exhausted survivors of the once-invincible Wehrmacht (German armed forces) whom Hitler had committed to the hopeless defense of his nation’s capital.

Within days Ploen itself, site of the Reich’s Number 1 U‑boat Training School, was suddenly vulnerable to attack. Units of British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery’s 21st Army Group were 20 miles/32 kilometers away. Dodging British warplanes overhead, Doenitz in his armored car, accompanied by truckloads of files and secret documents, reached the safety of Muerwik, just north of Flensberg next to the Danish border. Here the unlikely successor of Hitler as Staatsoberhaupt (Head of State), bearing the titles of Reichspraesident (President) and Supreme Commander of the German Armed Forces, assumed leadership of the moribund Nazi government—what Germany’s enemies called the “Flensberg government.” Doenitz stayed at his post until a small RAF task force took him and the main principals of his regime into custody on orders of Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower on May 23.

Karl Doenitz (1891–1980) was a tall, thin-lipped authoritarian age 54 when the Allies ended his wartime career. Not a member of the Nazi Party until 1944, Doenitz was in every respect the most loyal and trustworthy of Hitler’s paladins. Bewitched by the Fuehrer’s charismatic personality, Doenitz spoke warmly of Hitler’s “enormous strength” and shared the Nazis’ anti-Semitic views about “the poison of Jewry” and the evils of Soviet Bolshevism. More than any other senior military commander, Doenitz insisted that the interests of the state and the Wehrmacht were one and the same, turning a blind eye to the fiendish effects they had on each other.

Thrust into the role of chief puppeteer by Hitler’s suicide on April 30, 1945, Doenitz dispatched his first marionette, or emissary, Col. Gen. Alfred Jodl, Chief of Operations Staff of the German Armed Forces High Command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, or OKW), to Eisenhower’s Supreme Allied headquarters in Reims, France, on May 6. Doenitz dispatched his second emissary, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, head of the OKW, to Soviet Army HQ in Berlin on May 8. The two most senior officers in the German army signed back-to-back unconditional surrenders on behalf of their country’s military. Doenitz, Jodl, and Keitel were tried and convicted for crimes against peace and war crimes by the postwar International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, Germany. Doenitz served 10 years in prison and received a state pension on release. Jodl and Keitel, on the other hand, were additionally convicted of crimes against humanity and were hanged in 1946.

Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz’s Flensburg Government, May 2–23, 1945

|

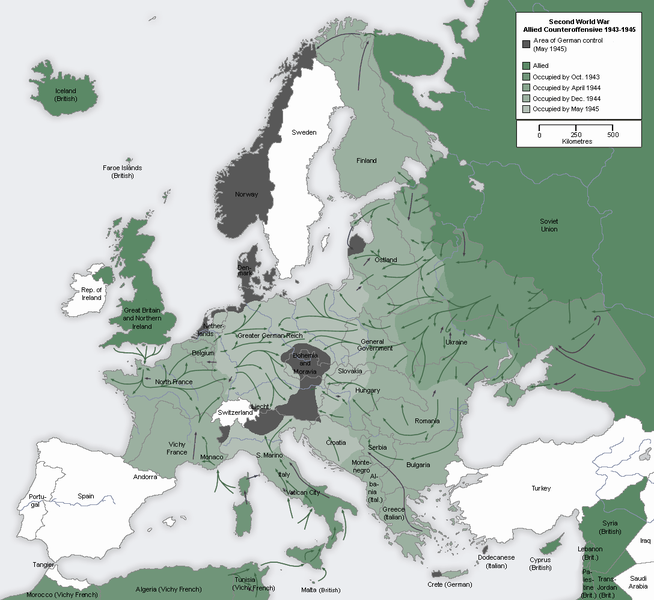

Above: Map showing extent of Flensburg Government control (dark gray), May 2–23, 1945. Headed by Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz, the Flensburg Government had de jure but little if any de facto control over the remnants of Hitler’s Third Reich, and none over the areas shown in shades of green. One American newspaper called the Flensburg Government (sometimes referred to as the Northern Government) a “fake government.” Named after Doenitz’s headquarters on the Schleswig-Holstein coast, the fledgling Flensburg Government attempted to rule the country following Hitler’s death (a “hero’s death,” Doenitz called it, not knowing it was suicide). The Doenitz “administration” (the label Winston Churchill chose to use)—unwilling to make a clean break from its Nazi past—was dissolved by order of Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower. The prescient Nazi Armaments Minister Albert Speer (pronounced “spare”), as soon as he learned that the hard-nosed Jodl had signed the German Instrument of Surrender in Reims, France, on May 7, prophesied correctly when he told Doenitz that “the sovereign rights of the German people have ceased to exist,” and that “the fate of the German people will be decided exclusively by the enemy.”

|  |

Left: Hitler receives Doenitz in late December 1944 or early 1945. Shortly before the military collapse of Nazi Germany and his suicide on April 30, 1945, Hitler transferred the leadership of the German state to the Admiral. Doenitz did not become Fuehrer (a post Hitler abolished in his political testament), but rather President (Reichspraesident) and head of the Germany’s armed services. Contrary to a 1941 decree that Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering would succeed him, Hitler had turned hours earlier on Goering and Reichsfuerher‑SS Heinrich Himmler, the second most powerful person in the country, for angling separately to make peace with the Western Allies. Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels would have become German Chancellor (Reichskanzler) in the post-Hitler government but for his own suicide hours after Hitler’s.

![]()

Right: Three members of the Flensburg Government—Doenitz (dark coat), Reich President and Minister of War; trailing him Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel’s replacement as head of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht Col. Gen. Alfred Jodl; and to Jodl’s left (in civilian attire) Albert Speer, Minister for Economics—in the custody of British Royal Hussars during Operation Blackout, May 23, 1945. Shortly after the men were taken into custody, Flensburg’s main street swarmed with British tanks and troops rounding up the remaining members of Doenitz’s administration and staff. In all, between 5,000 and 6,000 Germans, including hundreds of high-ranking military officers, were taken into custody. The 20‑day farce at Flensburg had come to its logical end. Most officers below the rank of colonel were released after a brief captivity. Doenitz and his cabinet were flown to England and imprisoned to await trial on war crimes charges. Tried by the 4‑power International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg (November 20, 1945, to October 1, 1946) Jodl was convicted and executed as a war criminal; Doenitz (unrepentant) and Speer (repentant) received prison terms of 10 and 20 years, respectively.

Contemporary Newsreel Account of Arrest of Flensburg Government Members

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click