GERMAN NAVAL, LAND, AIR UNITS OVERPOWER POLISH DEFENSES

Warsaw, Poland • September 1, 1939

Eighty-six years ago World War II in Europe began on this date in 1939 in Danzig (now the present-day Polish city of Gdańsk) when the elderly German training ship Schleswig-Holstein, under the guise of a ceremonial visit to the city, bombarded Poland’s naval base in Danzig harbor. After a fierce daylong fight Danzig fell and was annexed by the Reich the next day. The Polish Navy was attacked and was effectively destroyed in less than a week.

In the air war, Hermann Goering’s Luftwaffe, with its large fleet of modern aircraft, had no difficulty in achieving control of Poland’s airspace. The Luftwaffe first attacked the Polish town of Wieluń, deep inside Poland, destroying 75 percent of the town and killing close to 1,200 people, most of them civilians. Warsaw, Poland’s capital of 3 million—under heavy aerial bombardment since the first hours of the war—was attacked on September 10 (“Bloody Sunday”), besieged on September 13, and pummeled by 1,150 German aircraft on September 24. The Luftwaffe also hit railways, important roads, and Polish troop movements. On the ground nearly one-and-a-half million men from 6 panzer (armored) divisions, 10 mechanized infantry divisions, some 40 divisions of more conventional infantry, and several contingents of commandos from what would soon be called Brandenburgers thundered across the 1,250‑mile/1931‑km border. Accompanying this massive force was a horde of newsreel cameramen from Joseph Goebbels’ Propaganda Ministry and some Italian war correspondents to record Poland’s destruction.

As German ground units advanced from the northwest and north (Pomerania, Danzig, and East Prussia) and from the west and southwest (Silesia and German-allied Slovakia) (see map), with their goal of converging on Warsaw, Polish forces withdrew from their forward bases near the Polish-German frontier to more established lines of defense in the east. The Polish defense plan called for an encirclement strategy: Germans were permitted to advance in between 2 Polish Army groups in the line between Berlin and Warsaw-Łódź, at which point a Polish reserve army would move in and trap them. Polish military strategists, however, failed to predict the head-spinning pace of German panzer and motorized units, a miscalculation that led to the September 8 capture of Łódź in Central Poland, the country’s third-largest city. This proved to be a major setback to the Poles’ plan to defend the country west of the Vistula, the river that bisects Poland south to north as well as Warsaw itself.

Although the British and French had declared war on Germany on September 3, pledging to guarantee Poland’s independence, they made no promises that they would come to Poland’s aid immediately. (A look at the map of Central Europe showed Allied war planners that there was no easy way to do that except by an attack on Germany’s west flank.) Luftwaffe chief Goering hoped that the conflict would be over quickly, avoiding a world war. That all seemed likely when the last Polish Army group in the field surrendered on October 6, 1939.

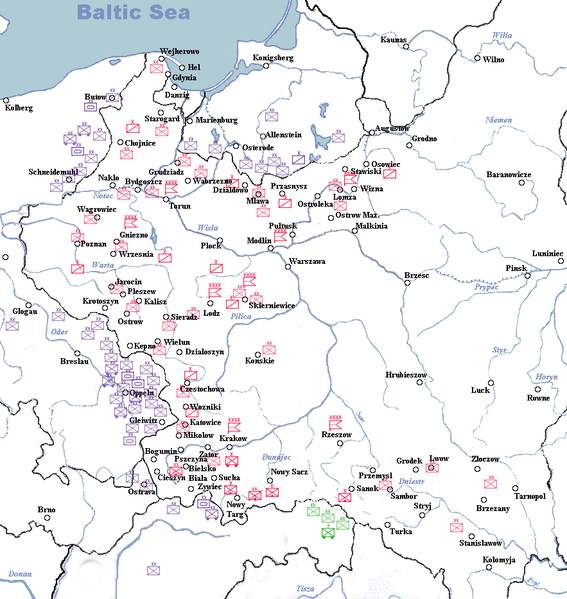

German Blitzkrieg Against Poland, September 1 to October 6, 1939

|

Above: German and Polish deployment of land forces on September 1, 1939. The German assault on Poland was the first demonstration of Blitzkrieg tactics—the rapid and ruthless use of armor, mobile infantry, and air support. (The term “Blitzkrieg” was coined by Western news reporters to describe the speed and destructiveness of the German attack on Poland.) The last engagement between the 2 enemies (Battle of Kock) took place between October 2 and 5 roughly 75 miles/121 km southeast of the Polish capital, Warsaw (Warszawa as it appears in the middle of this map). Adolf Hitler was convinced that once Poland was defeated and divided between Germany and the Soviet Union, which by previous agreement had entered the conflict against the Poles on September 17, 1939, Britain and France would not seriously continue the war.

|  |

Left: The Battle of Westerplatte was the first battle in the German invasion of Poland. Beginning on Friday, September 1, 1939, German naval and land forces assaulted the Polish Military Transit Depot on the Westerplatte peninsula in Danzig’s harbor. Manned by fewer than 200 Polish soldiers, the depot held out for 7 days in the face of heavy attacks that included dive bombers. In this photo German soldiers make a sweep of the area on September 8.

![]()

Right: Wieluń city center after 3 German air raids on September 1, 1939. The bombing of Wieluń, which held no military value, is considered to be one of the first terror bombings in history and maybe the second in Europe. The church, synagogue, hospital, and most of the town’s other buildings were destroyed by 70 tons of bombs. The casualty rate was more than twice as high as the Basque town of Guernica, Spain, bombed by German and Italian air forces in April 1937. On September 1, 2019, the President of Poland, Andrzej Duda, and the President of Germany, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, attended a memorial ceremony before dawn in Wieluń. The pair next moved to Piludski Square in Warsaw, to be joined by U.S. Vice President Mike Pence, for a second memorial ceremony marking the 80th anniversary of the start of World War II in Europe.

|  |

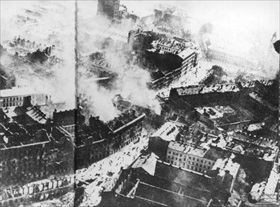

Left: Burning Warsaw, September 1939. The Luftwaffe opened the German attack on Poland’s capital on September 1, 1939, deploying 1,750 bombers and 1,200 fighters during the invasion. As the German Army approached Warsaw on September 8, Junkers Ju‑87 Stukas and other bombers attacked the city. On the 13th, Luftwaffe bombers caused widespread fires. Finally, on September 25 (“Black Monday”) Luftwaffe bombers, in coordination with heavy artillery barrages by army units, badly damaged Warsaw’s city center. Smoke from raging fires rose 10,000 ft./3,048 m into the air and could be seen 70 miles/113 km away. Hitler eagerly watched the destruction of the city through field glasses. The next day the Polish garrison of 140,000 men surrendered, and on September 27 German troops entered the city.

![]()

Right: From the first hours of the war, Warsaw—called the “Paris of the North” owing to the splendor of the city—was a target of unrestricted aerial bombardment. In addition to military facilities such as army barracks, the airport, and an aircraft factory, German pilots targeted civilian facilities such as water works, hospitals, market places, and schools. Between air raids and artillery shelling as the Germans approached, the Polish capital sustained 50,000 or 60,000 civilian deaths, more than the death toll in Allied raids on Hamburg in mid‑1943 (Operation Gomorrah) and Dresden in February 1945. Forty percent of Warsaw’s buildings were damaged and 10 percent were destroyed in the first month of war. In this photo a 9‑year-old boy rests in the city’s rubble during a search for food for his family.

September 1, 1939: Hitler’s Germany Invades Poland, Triggering World War II

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click