GERMAN ARMY BACKS HITLER

Berlin, Germany • April 11, 1934

On this date in 1934 German Chancellor Adolf Hitler secretly met with German War Minister Gen. Werner von Blomberg, the unofficial representative of the officer corps of the Reichswehr (German armed forces), and reached an agreement that sealed the fate of the post-World War I Weimar Republic. Behind titular President Paul von Hindenburg’s back, Hitler secured the Army’s support to become German president upon Hindenburg’s imminent demise. Many high-ranking Army officers, like Gen. Ludwig Beck, Chief of the General Staff in 1934, placed their faith in Hitler to restore Germany’s place as a European superpower after the forced disarmament and reduction in size and equipment imposed on its armed forces by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles.

In return for the Army’s support Hitler promised to rein in his Nazi Party’s brown-clad praetorian guard, the 400,000-strong SA, short for the German Sturmabteilung, or “storm troopers” (not to be confused with the elite SS, or Schutzstaffel). The SA’s thuggery under its leader and one-time Hitler intimate, the portly homosexual Ernst Roehm, had greased Hitler’s rise to power. But now it threatened the Reichswehr’s position as the true national defense force. Roehm had always seen his SA as a people’s army and replacement for the Reichswehr (the SA also supplied him with young boys), whereas Hitler was favorably inclined toward the traditional power groups: the Reichswehr with its old-school Prussian traditions, the aristocracy, and the industrial and financial magnates.

Hitler’s cynical betrayal of the SA became known as “The Night of the Long Knives,” a decapitation of the SA leadership by another of Hitler’s creations, the Schutzstaffel (“Protection Squadron”), which began on June 30, 1934. Not only were Roehm and other influential SA officials eliminated by the SS, but other miscellaneous figures such as Gen. Kurt von Schleicher, former German Chancellor thought to be scheming with Roehm, and Gregor Strasser, fallen leader of the left-wing faction of the Nazi Party. Hitler justified the murder of as many as 100 of his opponents and the arrest of over a thousand “mutineers” in a two-hour speech on July 13 to the Reichstag, now short thirteen members who had been killed in the “Roehm Putsch.”

The failing 86-year-old Hindenburg was given a telegram drafted by Nazi Party members, which he dutifully sent to Hitler, congratulating him on having “nipped treason in the bud” and saving “the German nation from serious danger.” Upon Hindenburg’s death on August 2, 1934, Hitler’s cabinet appointed their leader Fuehrer und Reichskanzler, a merger of offices confirmed in a national plebiscite (89.9 percent voting in favor) on August 19, 1934.

![]()

Rise and Fall of Sturmabteilung (SA) Chief Ernst Roehm (1887–1934)

|  |

Left: Although the German public did not complain much when Sturmabteilung (SA) activities were directed against Jews, communists, and socialists, by 1934 there was general concern about the level of civic violence for which Roehm’s “Brownshirts” were responsible. This photo shows Roehm’s (and by extension, Hitler’s) thuggish workforce in front of a Jewish shop during the boycott of Jewish businesses in Germany on April 1, 1933. The sign says: “Germans, Attention! This shop is owned by Jews. Jews damage the German economy and pay their German employees starvation wages. The principal owner is the Jew Nathan Schmidt.”

![]()

Right: Hitler posing in Nuremberg’s Main Market Square, 14th-century brick Gothic Frauenkirche (“Church of Our Lady”) as a backdrop, with SA members during the Fourth Nazi Party Congress, August 1–4, 1929. In the foreground, bedecked as usual in medals, is Hermann Goering. Goering, Nazi propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels, and Schutzstaffel (SS) head Heinrich Himmler plotted the demise of the SA. Goering personally reviewed the list of detainees who were to be killed in the “Night of the Long Knives” (German, Nacht der langen Messer).

|  |

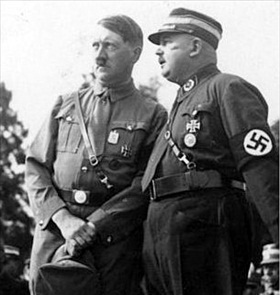

Left: Mustered out of the Kaiser’s army as a captain, Ernst Roehm continued his military career as an adjutant in the Reichswehr, the much diminished defense force of the Weimar Republic (1919–1935). In 1919 he joined what became the Nazi Party and he and Hitler became close friends. He was tried along with Hitler for participation in the November 1923 Munich Beer Hall Putsch. From his prison cell in Landsberg, Bavaria, Hitler gave Roehm permission to rebuild the Sturmabteilung any way he saw fit. Under both men the SA grew to number over one million men who engaged in street battles with communists and Jews. Hitler is pictured with SA Chief of Staff Roehm at the 1933 Nuremberg Party Rally.

![]()

Right: Hitler triumphant. SA troops parade past Hitler during the 1935 Nuremberg Party Rally. Hitler admitted in a speech to the Reichstag on July 13, 1934, that the killings connected with the “Night of the Long Knives” had been illegal but claimed a plot had been underway to overthrow the government. (For his Reichstag speech Hitler ordered the German secret police (Gestapo) to produce an “official” casualty list: 61 shot dead, 13 allegedly died resisting arrest, and 3 suicides.) A tame Reichstag passed a measure that retroactively made the action legal.

Adolf Hitler, Ernst Roehm, and the Night of the Long Knives

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click