GERMAN ANTI-WAR NOVEL DEBUTS

Berlin, Germany · January 29, 1929

On this date in 1929 Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (German, Im Westen Nichts Neues) debuted in book form after being serialized in a German newspaper in late 1928. In the story Remarque, who was a conscript during the First World War, described the German soldiers’ extreme physical and mental stress in combat, graphically depicted German and French boys and men butchering one another during battle, and exposed the detachment from civilian life felt by many of these soldiers upon returning home. The novel was a searing indictment of the Great War. It sold 2.5 million copies within 18 months and was translated into 25 languages, making it the best-selling novel of the 20th century up to that time.

In 1930 the novel was turned into a motion picture starring Lew Ayres, who played Paul Baeumer, the novel’s central character and narrator. The sensitive 19‑year‑old was urged on by his school teacher to join the Kaiser’s army shortly after the start of World War I. The movie ends with Baeumer’s death and the German Army’s situation report for that day: “All is quiet on the Western Front.” The movie captured Oscars for Best Picture and Best Director in 1930.

On May 10, 1933, Adolf Hitler’s 3-1/2-month-old Nazi government, instigated by Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, banned and publicly burned Remarque’s novel, banned the film after staging riots outside movie houses that showed the picture (it remained banned in Germany until 1945), and produced propaganda claiming that Remarque was a descendant of French Jews and that his real last name was Kramer, a Jewish-sounding name. Not surprisingly, Remarque left Germany, moving to Switzerland. In 1938 his German citizenship was revoked. A year later he and his wife moved to the U.S. and became naturalized citizens.

Remarque’s sister, Elfriede Scholz, who had stayed behind in Germany with her husband and two children, was arrested by the Gestapo in 1943. After a short trial in the Volksgerichtshof, Adolf Hitler’s extra-constitutional “People’s Court,” presided over by the notorious Nazi jurist Roland Freisler, Scholz was found guilty of “undermining morale” for stating that she considered the war was lost. Freisler told the defendant, “Your brother has unfortunately escaped us—you, however, will not escape us.” She was guillotined on December 16, 1943.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”033349556X,0312421133,0449911497,0307408841,0205695329,0691116938,0465085725,0582437563,0674350928,0691157960″ /]

Erich Maria Remarque and His Anti-War Novel

|  |

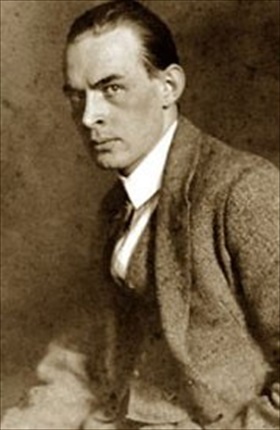

Left: Thirty-year-old Erich Maria Remarque (1898–1970). Upon release of his book All Quiet on the Western Front and the movie of the same name, Remarque emerged as an eloquent storyteller for “a generation of men who, even though they may have escaped [its] shells, were destroyed by the war,” “living soldiers [i.e., the war’s survivors] as old and dead, emotionally drained and shaken,” unable to fit into the postwar world.

![]()

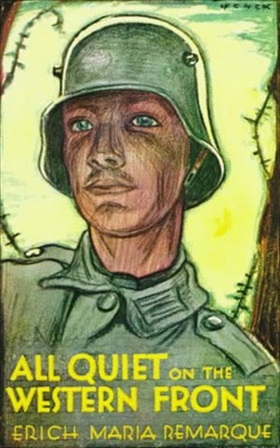

Right: Cover of first English language edition. Design was based on a German World War I war bonds poster. The title of the book and the movie underscored the cosmic insignificance of one person’s death (Paul Baeumer’s) in a war that took the lives of 16 million people (military and civilians) and wounded 20 million more.

Movie Clip from 1930 All Quiet on the Western Front

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click