FRENCH INDOCHINA NOW OURS—JAPAN

Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City), French Indochina · July 25, 1941

On September 21, 1937, Japanese planes bombed the capital of China, Nanking, shortly after igniting the Second Sino-Japanese War. President Franklin D. Roosevelt expressed the shock of “every civilized man and woman” over “the ruthless bombing” of Chinese civilians. Generally, however, U.S. and European reaction to Japanese aggression in China was mostly bark and no bite. Just under two years later, Adolf Hitler’s Luftwaffe bombed the capital of Poland, Warsaw, launching (as Europeans viewed it) the Second World War. But again, with the October 1939 onset of the so-called Phony War (Sitzkrieg, or “sitting war” in German), there was a lot of barking but little action. Not until April 1940, when Hitler turned his attention to Western Europe and wolfed down Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France in less than three months, was the bark of the last dog standing—Great Britain—matched with bared teeth.

Back in Asia, the Japanese government and the German puppet regime of Vichy France signed a treaty in mid-September 1940 permitting the stationing of Japanese forces in parts of northern French Indochina (in what is now Vietnam). Four months later, at the end of January 1941, Japan threw its weight behind a negotiated end to clashes between Vichy French forces and those of Thailand along their contested border. The Japanese-imposed armistice not only confirmed Japan’s military occupation of French Indochina (modern-day Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos), but it opened the Vichy colony to mineral and agricultural exploitation by Tokyo’s expansionists in what Japan was calling the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere under its leadership. Economic collaboration was formalized by a treaty in early May.

On this date, July 25, 1941, Japan cemented its relationship with Vichy France by moving air and naval forces into Southern Indochina and declaring the whole French colony a Japanese protectorate. Japan’s move set off a three-day whirlwind of activity by Western governments, which in protest froze Japanese assets in the U.S., Canada, Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand, and the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia). The U.S. and the Dutch government-in-exile, both of which controlled vast oil reserves, upped the pain by halting shipments of oil and motor fuel to Japan, turning off 80 percent of Japan’s oil imports. The next moves by Japan’s military were predictable.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0582493498,1439183244,1591145201,0520088239,1439210454,080144926X,0823224724,1442612347,0691145067,1137270357″ /]

Japan’s “Place in the Sun”: The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, 1940–1945

|

Above: Maximum extent of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, 1942. Based on a geographically smaller version called the New Order in East Asia (late 1938), the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere was invoked into being in late June 1940. Japanese idealists, nationalists, economic expansionists, and the military were all drawn by varying degrees to the “Asia for Asians” concept. Principal actor in the cast of players was the Japanese military, whose role was to secure by conquest the raw materials that were unavailable on the four home islands of Hokkaido, Honshū, Shikoku, and Kyūshū. Although Japan succeeded in stimulating anti-Western sentiment as “elder brother,” the Co-Prosperity Sphere never materialized into a unified East Asian block economically or militarily.

|  |

Left: Japanese 10-sen (1/10th of a yen) stamp from 1942 depicting the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

![]()

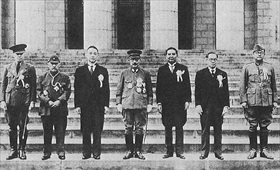

Right: Six “independent” participants and one observer attended the Greater East Asia Conference, a sort of Asian summit held in Tokyo in early November 1943. Standing in front of the Japanese Diet, or national parliament building, are (left to right) Ba Maw, head of Japanese-occupied Burma (State of Burma); Zhang Jinghui, Prime Minister of Japan’s puppet state of Manchukuo (Manchuria); Wang Jingwei, head of the Japanese puppet government of China (Reorganized National Government of China); Hideki Tōjō, Prime Minister of Japan; Prince Wan Waithayakon, envoy from the Kingdom of Thailand; José P. Laurel, President of the Japanese-sponsored Second Philippine Republic; and Subhas Chandra Bose, Head of State of the Provisional Government of Free India (the “observer,” since India was still under British rule). In a joint declaration, the participants praised Asian solidarity and condemned Western colonialism but could not produce any practical plans for either economic development or integration. The Co-Prosperity Sphere collapsed with Japan’s surrender to the Allies in August 1945.

Japanese Expansionism in China and Southeast Asia During 1930s, Early 1940s

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click