FORMAL FLAG-RAISING OVER BATTERED IWO JIMA

Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands • March 14, 1945

On this date in 1945 the U.S. flag was raised over the 8.1‑sq‑mile/21‑sq‑km island of Iwo Jima in a formal flag-raising ceremony. The Battle of Iwo Jima (February 19 to March 26, 1945)—a battle for the isolated and barren Japanese-held island lying some 760 miles/1,223 km southeast of Tokyo—was the most bitterly contested of the war. Iwo Jima’s capture was a prelude to the battle for Okinawa, 340 miles/547 km closer to the Japanese Home Islands.

Japanese Army and Navy troops had burrowed deep into the volcanic rock and black powdery soil, creating a defensive stronghold of well-concealed tunnels, bunkers, machine-gun nests, and spider (one‑man) holes intended to inflict maximum casualties on U.S. forces and delay their progress toward their homeland. Each side inflicted enormous carnage on the other, partly because the barren terrain offered little cover, and partly because the key weapons for clearing out the thousands of Japanese positions were hand grenades, handheld flamethrowers, and “Ronson” or “Zippo” tanks that shot flaming liquid on targets almost 500 ft/152 m away.

Nearly 22,000 Japanese defenders died or committed suicide during the 36‑day campaign, which began on the third Monday of February 1945 when U.S. landing craft unloaded 30,000 men from the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Marine Divisions (the first of 70,000), along with amphibious vehicles and equipment, on a 2‑mile-long/3.2‑km-long invasion beach on the island’s southern coast and on a second landing site north of Mt. Suribachi on the western coast. Marines, sailors, and Seabees suffered over 6,700 killed out of some 26,500 casualties, 548 men killed out of 2,420 casualties the first day. Identified as “Hot Rocks” in the operations plan for its assault, Mt. Suribachi, at 556 ft/169 m the defining geographical landmark on the island as well as the site of the flag-raising made famous by Joe Rosenthal’s iconic photograph, was captured on February 23. Later that day Chaplain Charles Suver and his assistant trudged to the mountaintop and promptly celebrated Mass under the flag while other Marines were still clearing nearby caves of Japanese defenders. His altar—a board propped across two empty fuel drums. On Easter, a Presbyterian chaplain held services there complete with a volunteer choir of Marines.

Capturing Iwo Jima, which lay midway between the Mariana Islands and Japan, had been motivated by the desire to fly long-range P‑51 Mustang fighters from the island to escort 4‑engine B‑29 heavy bombers from their Mariana bases in daylight raids on Japan. That proved unnecessary when U.S. Army Air Forces resorted to low-altitude (under 10,000 ft/3,048 m) night aerial attacks that met no significant Japanese resistance. For the rest of the war the island served as an emergency landing strip for American bombers that were damaged by antiaircraft fire, low on fuel, and/or carrying wounded crewmen returning from a bombing run. (The first crippled B‑29 to make an emergency landing, Dinah Might, did so as U.S. Marines were still fighting to secure the island.) Some 2,400 emergency stops were made over the next 5 months, saving more than 27,000 trained and therefore valuable airmen from an uncertain fate when their planes landed safely on Iwo Jima’s airstrips. Perhaps equally valuable to the war effort were the damaged aircraft that were repaired and returned to service.

Battle of Iwo Jima, February 19 to March 26, 1945

|

Above: Location of the pork-chop-shaped island of Iwo Jima in relation to Tokyo (760 miles/1,223 km due north) and the Mariana Islands (Saipan, 650 miles/1,046 km to the southeast). Iwo Jima was a Japanese citadel protecting the homeland. Iwo Jima had 2 completed airstrips with a third under construction. American intelligence reported that there were 13,000 Japanese defenders on the island, when in fact there were nearly 22,000. Japanese aircraft from Iwo Jima were able to bomb U.S. B‑29 bases in the Marianas, and radio operators on Iwo Jima were able to send advance warning to the Japanese Home Islands every time flotillas of the long-range Superfortresses passed north overhead. Operators were also able to garner advance notice of U.S. air strikes directed at Iwo Jima itself.

|  |

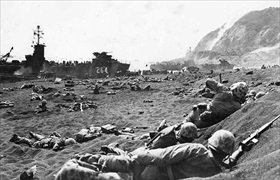

Left: Members of the 1st Battalion 23rd Marines burrow in the black volcanic sand the size of BBs on an Iwo Jima beach while their fellow Marines unload supplies and equipment from landing craft under a rain of artillery fire from Japanese positions in the background. Amphibious tractors floundered in the sandy soil and trenches and foxholes collapsed as soon they were dug. Marines crawled across the island’s blasted landscape yard by yard/meter by meter searching in vain for cover. A colonel who had landed 900 men on the morning of L‑Day (landing day) reported only 150 men were still on their feet at the end of the first day.

![]()

Right: A Marine fires his Browning M1917 machine gun at a Japanese position. Marines encountered intense artillery fire on Iwo Jima. Japanese troops on the island citadel served under their ingenious and courageous commander, 53‑year-old Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi. A deputy military attaché to Washington, D.C., in the late 1920s, Kuribayashi was a veteran of the conquest of Hong Kong (December 18–25, 1941), served as the chief of staff of the Japanese 23rd Army, and then commanded the prestigious Imperial Guards Division in Tokyo. A strong believer in the concept of defense in depth, he and his men were responsible for the deaths of a third of all U.S. Marines killed during the entire 4‑year Pacific conflict. Twenty-seven Medals of Honor were awarded to Marines and sailors, many posthumously, more than were awarded for any other single operation during the war.

|  |

Left: A U.S. 1.5‑in/37‑mm gun fires against Japanese cave positions in the north face of 556‑ft‑tall/169‑m-tall Mt. Suribachi, an extinct volcano. These light but extremely accurate weapons did some of their best work in the southern part of the island. Over 35 days approximately 28,000 combatants died, including 6,821 Americans and nearly 22,000 Japanese by fighting or ritual suicide, making Iwo Jima one of the costliest battles of World War II. Indeed, unique among Marine battles, total U.S. casualties (wounded and dead) exceeded those of the enemy. Only 216 Japanese defenders were captured during the cataclysmic battle. Marines came to grudgingly respect the bravery of the Japanese soldier on Iwo Jima and agree that Gen. Kuribayashi was the best defensive commander they faced in the Pacific War.

![]()

Right: Joe Rosenthal’s Pulitzer Prize-winning black-and-white image depicts 6 Marines raising the Stars and Stripes over Mt. Suribachi on February 23, 1945, 5 days into the Battle of Iwo Jima. Their 8 ft by 4 ft 8 in/2.4 m by 1.45 m flag, borrowed from a Navy LST (Landing Ship, Tank), replaced a smaller one (5 in by 28 in/1.4 m by 0.7 m) raised by 40 Marines earlier in the day. “Horns and sirens all over the island erupted and even the ships offshore chimed in,” one Marine witness recalled. Another Marine said at the time that the iconic moment “didn’t mean anything to me. All it meant was that now we won’t take any fire from behind us.” Three of the flag-raisers depicted in the Rosenthal photo died at Bloody Gorge on the north side on the island, where the worst of the fighting took place. Three flag-raisers—Harold “Pie” Keller (formerly thought to have been Pvt. Rene Gagnon), Pvt. Ira Hayes, and Pvt. Harold Schultz (formerly thought to have been Pharmacy Mate Second Class John Bradley)—survived the horrific combat. Bradley, Gagnon, and Hayes participated in a war bonds tour in the States that featured reenactments of the flag raising. Secretary of the Navy and eyewitness James Forrestal remarked that the flag-raising image would ensure the existence of the U.S. Marine Corps for the next 500 years. Former Army Air Forces captain and Commander-in-Chief of all U.S. Armed Forces President Ronald Reagan said: “Some people spend an entire lifetime wondering if they made a difference in the world. But Marines don’t have that problem.” Today, a pristine white monument dedicated to the Fifth Marine Division, whose men raised the famous flag, sits on the forward edge of Mt. Suribachi’s peak, facing the landing beaches below. Returned to Japanese jurisdiction in 1968, Iwo Jima welcomes civilian visitors once a year.

Contemporary Color Documentary from U.S. Government Office of War Information: “To the Shores of Iwo Jima”

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click