FIRST U.S. ARMY STUMBLES AT BATTLE OF SCHMIDT

Schmidt, Huertgen Forest, Germany • November 2, 1944

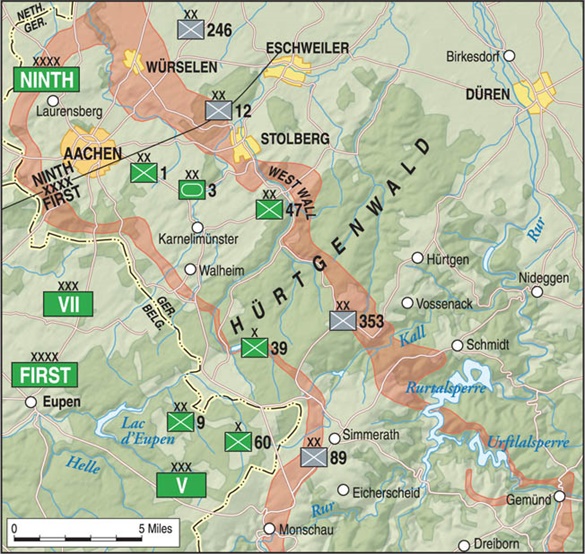

On September 19, 1944, elements of Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’ First U.S. Army entered the 10‑mile/16‑km-wide, 20‑mile/32‑km-long Huertgen Forest (German, Hürtgenwald) southeast of the ancient city Aachen, the first major and westernmost city in Nazi Germany to have fallen to the Anglo-American-Canadian armies. Before the outbreak of World War II, there was no specific area known as the Huertgen Forest, a relative compact area of just over 50 sq. miles/130 sq. km about 3 miles/5 km east of the Belgian-German border (see map below). The wooded area that received that name on American maps was actually a plot of forested land that was the northernmost tip of the Ardennes region of Germany. A plateau of volcanic origin, it appeared to be a region of hills because of the many streams that gouged their way through the area. Scattered villages within the dark and forbidding forest provided the only shelter and road network in the area. One such village was Huertgen itself, which gave the forest its name. Another was the strategically important village of Schmidt, which controlled many key roads through the forest and commanded the western approaches to the largest Rur (or Roer) flood control and hydroelectric dams (Rurtalsperre and Urfttalsperre on map). Tragically, Schmidt emerged as key to the grim and bloody 3‑month-long Battle of the Huertgen Forest, the longest single battle the U.S. Army has ever fought and, as it turned out, one of the most wasteful American operations in the whole European war.

To be fair to the decision makers of those bygone days, the frantic retreat of the German armed forces in France in the summer and autumn of 1944 led Hodges and his corps commanders, as well as higher ups at Supreme Allied headquarters, to think the Wehrmacht was much weaker than the Allies were at the moment. They were victims of their own surprising successes and momentum. Truth was, the resultant strain in logistical, tactical, and operational capabilities of the Allied armed forces caused by their rapid pursuit of the enemy led to a number of military stumbles, the biggest, most dangerous for the Americans being the Ardennes Offensive (Battle of the Bulge), which kicked off on December 16, 1944. Hodges’ failed combination of forest-clearing operations in the Huertgen Forest and a decisive breakthrough toward the wide and flat plain leading directly to the Rhine River across from which was the Western Allies’ lodestone, the Ruhr, Germany’s industrial heartland, was a stumble of a lesser magnitude.

By mid-October the Americans had renewed their efforts in the Huertgen Forest. On this date, November 2, 1944—All Souls’ Day in Germany—Hodges ordered the 109th, 110th, and 112th infantry regiments from Maj. Gen. Norman “Dutch” Cota’s 28th Infantry Division to capture the town of Schmidt. Schmidt lay on 1 of 2 German-occupied parallel ridges formed by a very deep gorge through which ran the freezing Kall, a small river. Using a precipitous trail the 112th regiment crossed the gorge and river with great difficulty yet managed to overwhelm the German garrison and take its objective, the village church, by nightfall the next day. The other 2 infantry regiments found moving forward a tough slog in the thick woods and in awful weather. Neither regiment crossed the Kall nor converged on Schmidt, which now made for 3 distinct battlegrounds.

The defenders counterattacked, shaping the battlefields from their hilltop vantage point and controlling the battles’ pace and outcomes. TThey mauled the 3 U.S. regiments in piecemeal fashion, directing most of their fury at the 112th regiment occupying Schmidt, which alone suffered 2,316 casualties out of a total strength of 3,100. The bitter confrontation ended on November 8 when Cota ordered a withdrawal. The 28th Infantry Division lost 6,184 out of 16,000 attached men as of November 2, making the 7‑day Battle of Schmidt (German, Allerseelenschlact) among the worst U.S. battlefield losses up to that time.

Hellacious Battle of Huertgen Forest, September 19 to December 16, 1944

|

Above: Map of the Hürtgenwald (Huertgen Forest) and surrounding villages. The terrain consisted of an expanse of tall, dense pinewoods rising from steep rocky crags and treeless ridges laced by plunging valleys and deep winding ravines and streams in the Eifel Mountains of the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. The Americans’ assumption that the Huertgen Forest-clearing campaign by elements of Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’ First U.S. Army would be short-lived was itself short-lived after initial attempts to penetrate the hilly and wooded forestland were thwarted by the difficulties of the terrain and the stout resistance of the Wehrmacht. Furthermore, U.S. troops underestimated German defenses in the Huertgen Forest, which, unbeknownst to the Western Allies, had become a staging area for Adolf Hitler’s planned Ardennes Offensive—the Battle of the Bulge (December 16, 1944, to January 25, 1945). (Hodges’ first thought was that Hitler’s Ardennes Offensive was a spoiling attack intended to disrupt his own forest-clearing campaign.) Hodges’ Huertgen Forest misadventure cost the First Army at least 33,000 killed and wounded of the 120,000 men deployed. The 33,000 figure included 9,000 friendly-fire and noncombat casualties among men suffering from hypothermia, frostbite, pneumonia, trench foot (aka immersion foot), self-inflicted wounds, and combat exhaustion (8,000 cases of “psychological collapse”). The Germans suffered 28,000 combat and noncombat losses, of which 12,000 were fatalities. Not until February 23, 1945, did U.S. forces finally clear the Huertgen Forest of enemy soldiers and ford the Rur (Roer) River on their way to the Rhine.

|  |

Left: 110th Infantry riflemen advance warily through the Huertgen Forest near the town of Vossenack northwest of Schmidt, early December 1941. Note the forbidding forest mass, which significantly favored the defenders. The dark green fir trees, rising to heights of 75 to 100 ft/22.8 to 30.5 m, were thick and intertwined. Trees stood as close as 4 ft/1.2 m from each other—impossible for tanks to navigate. Most days’ sunlight never penetrated to the forest floor, which was constantly wet, a result of all the streams flowing through the area and the lack of daylight on the sunniest days. The dismal forest reminded intruders of the type immortalized in old German folk tales. Cota was unhappy with the operations order 28th Infantry Division was given and said so, but his complaints were given short shrift by V Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Leonard Gerow, his immediate superior and by Hodges, who responded to Cota’s observations with icy silence. After the battle Cota confessed to an interviewer that he doubted his men ever had a gambler’s chance of success.

![]()

Right: Taking up defensive positions in a clearing in the Huertgen Forest, soldiers of the 28th Infantry Division prepare to engage the enemy.

|  |

Left: The meat grinder that was Schmidt (undated photo). Cota’s 28th Infantry Regiment was assigned to capture the town of Schmidt to secure the right flank of Maj. Gen. “Lightning Joe” Collins’ VII Corps advance on the Rhine. (VII Corps, First Army, was the southern pincer of Omar Bradley’s 12th Army Group.) Schmidt sprawled spread-eagled across a bald ridge. Whoever held the town would also control the road network and Rur River dams. On November 4, a day after vacating Schmidt, the Germans hit the 112th infantry regiment with a superior number of fearless infantrymen and supporting armor. Unnerved, American units wavered and panicked, abandoned their wounded, and tore for the exits. It was sheer bedlam. Cota faced reality: he was no longer in control of his Huertgen Forest-clearing operation and faced being penned in. On November 8, under a freezing cloudburst and enemy mortar fire, many of Cota’s tattered remnants set out in single file, each GI holding the shoulder of another, for safety behind friendly lines. It was the last time the 28th Infantry Division would see action in the Huertgen Forest. Not until February 10, 1945, was Schmidt permanently in American hands, this courtesy of Gen. James Gavin’s 82nd Airborne Division.

![]()

Right: Despite the painful American retreat that ended the Battle of Schmidt (November 2–8, 1944), the U.S. Army and the U.S. Army Air Forces continued to blast away at the tenacious German hold on the Huertgen Forest. Nearly 100,000 Allied soldiers fought in or near the dreary forest in the effort to expel the enemy. Six days after Cota’s men abandoned Schmidt, 1,191 Boeing B‑17 Flying Fortress of the U.S. Eighth Air Force dumped 4,000 tons of fragmentation bombs on the ruins of Schmidt. Heavy bombers and 1,000 fighter bombers of the Ninth Air Force followed in their wake with yet more fragmentation explosives and millions of 50‑caliber rounds. Late in November a regiment from Gerow’s V Corps 8th Infantry Division, with armor support, drove the stubborn defenders out of nearby Huertgen town. German mortar and artillery rounds continued to pummel the town after its capture, turning it to rubble. This photo shows weary 8th Infantry riflemen tramping through a treeless vista and desolate villagescape that was once Huertgen.

Battle of Huertgen Forest: Unrelenting Bloodbath in Woods Southeast of Aachen

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click