FINNISH AID TO DISRUPT NAZI ORE IMPORTS

London, England · December 19, 1939

In the afternoon of August 23, 1939, Adolf Hitler’s foreign secretary Joachim von Ribbentrop appeared in Moscow’s Kremlin fortress to sign off on the Nazi-Soviet Nonaggression Pact. The 10‑year pact, also known by the twin surnames of the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Ribbentrop, was the necessary “green light” Hitler needed to finally make good on his intentions to end the cartographic existence of his eastern neighbor, Poland. Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, extracting the maximum possible concessions from an obsessive Hitler, demanded “an additional agreement that will not [be] published anywhere else,” a secret protocol that set out “spheres on interest” in Central and Eastern Europe and Scandinavia for each of the totalitarian states. After a telephone call to Hitler at his Bavarian retreat, the Berghof, Ribbentrop was able to inform Stalin and his foreign minister, Vyacheslav Molotov, that “the Fuehrer accepts [Soviet terms].” And so the pact with its secret attachment was signed amid many celebratory toasts (vodka and Crimean champagne) in the early in hours of August 24, 1939.

The Winter War between Finland and the aggressor Soviet Union predictably broke out on November 30, 1939, following Hitler and Stalin’s agreement 2½ months earlier to partition Poland, Finland, and the Baltic states of Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania between themselves. The French and British governments, ignorant of course of the “spheres of influence” into which the two totalitarian states could insert themselves, strongly desired to aid the outmanned and outgunned Finns (population 3.5 million) with volunteers and war materiel. The only possible route for such aid was through the Scandinavian countries of Norway and Sweden, both neutrals.

The Allied Supreme War Council, consisting of British and French military advisers, decided on this date, December 19, 1939, to send help to Finland, should it be requested, against the wishes of the neutral Scandinavian states. The Allies, at war with Nazi Germany since September 3, recognized that a new dynamic might give them a chance to interrupt their enemy’s imports of Swedish iron ore (9 million tons out of 22 million in 1938) if Narvik, an ice-free port in Northern Norway closest to the major Swedish mining district, became an Allied supply base for Finnish assistance. The British War Cabinet hoped that direct aid to Finland via Norway would provoke Nazi Germany into taking counterproductive measures that might nudge neutral Norway and Sweden into the Allied camp.

The unreal assumptions held by the British and French governments regarding Scandinavia would have huge consequences in the second week of April 1940, when Hitler surprised the Western Allies with Operation Weser-Exercise (Unternehmen Weseruebung), the occupation of Denmark and Norway. Sweden remained neutral throughout World War II, exporting ore through its ice-free southern ports, thus removing German reliance on Narvik as a shipping port despite its eventual occupation following the two Battles of Narvik (April 9 to June 8, 1940). For its part Finland emerged as a natural-born ally of Nazi Germany in June 1941, taking part in the invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa), though careful not to do so as an Tripartite (Axis) treaty member. As for Swedish iron ore exports, the fall of France to Hitler’s Wehrmacht (armed forces) in May and June 1940, which added the Lorraine fields in Eastern France to the iron ore resources available to the German war machine, meant that Sweden and Norway no longer dominated the conversation of German armaments ministers in the same way they had earlier.

Western Allies and Nazi Germany Engage in Scandinavian Contest

|

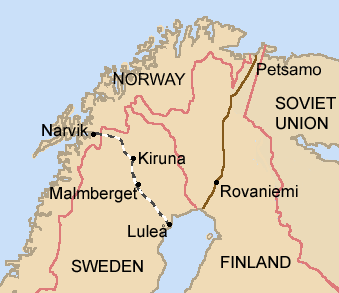

Above: Swedish iron ore was extracted in Kiruna and Malmberget and brought by rail to ice-free Narvik harbor in neutral Norway and Sweden’s Luleå harbor. Luleå harbor and surrounding sea were blocked by ice in the winter. The May–June 1940 German conquest of France, with that country’s iron ore fields in Lorraine, minimized the importance of Scandinavian exports to Germany.

|  |

Left: Narvik provided an ice-free harbor in the North Atlantic for iron ore transported by rail from Sweden’s Kiruna ore mine. Both sides in the war had an interest in denying this iron supply to the other, setting the stage for a resumption of large-scale land battles in April 1940 following the German and Soviet invasions and annexations of Poland 8 months earlier.

![]()

Right: The total number of Norwegian defenders during the Battle of Narvik (April 9 to June 8, 1940) was 8,000–10,000. French, British, and Polish forces in and around Narvik brought the total Allied force to 24,500 men. Facing them were 5,600 German soldiers, paratroopers, and shipwreck sailors.

|  |

Left: The Battle of Narvik, touched off by the German capture of the vital rail terminus and harbor in Norway’s north at the start of Operation Weseruebung, provided the Allies with their first major land victory in World War II on May 29, 1940.

![]()

Right: However, the successful German attack on France in May and June 1940 forced the Allied expeditionary force to evacuate Norway, which these British soldiers did in June. Without Allied air and naval support, the Norwegians at Narvik were forced to lay down their arms, doing so on June 10, 1940, the last Norwegian forces to surrender their country to the invaders.

Newsreel of German Invasion of Denmark, Norway, Belgium, and the Netherlands

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click