FIERCE FIGHTING AT SAN PIETRO AS U.S. FIFTH ARMY ADVANCES NORTH

San Pietro Infine, Southern Italy • December 17, 1943

On this date in 1943 what little remained of the ancient Italian farming community of San Pietro Infine, population 1,400, fell to the U.S. 36th (“Texas”) Infantry Division of Lt. Gen. Mark Clark’s U.S. Fifth Army—this after the collapse of the Bernhardt Line (or Reinhard Line), an outlying spur of the heavily fortified German “Winter Line” (see map below). Seizing German-held San Pietro Infine straddling the strategic intersection of Route 6 and the Bernhardt/Reinhard Line had been important to Clark’s Fifth Army, now joined for the first time by troops of the reconstituted Royal Italian Army (Regio Esercito) after Italy declared war on former Axis partner Germany in October 1943. Since September hundreds of German troops had taken up positions in San Pietro Infine and since early November at the nearby choke point known as the Mignano Gap. The mile/1.6‑km-wide gap was a 6‑mile/9.6‑km-long corridor through which Route 6, the main north-south highway on the Italian peninsula, meandered past San Pietro Infine and Monte Cassino (10 miles/16 km further up the highway) to the plain of the Liri Valley and thence to Rome, the prize which the Germans fought to keep and the Western Allies sought to take.

The Battle of San Pietro emerged as a major engagement in the Italian Campaign (July 1943 to May 1945). The town, with its thick stone walls, steeply terraced terrain, narrow booby-trapped approaches, and commanding view of Route 6, was occupied by 2 battalions of the tough 15th Panzergrenadier Regiment, German Tenth Army soldiers whom Hitler had ordered to hold out for as long as possible. Dominating the town was the treeless Monte Sambúcaro (Sammucro on Allied maps) and 2 other steep mountains facing Sambúcaro, Mts. Lungo and Rotondo. After Clark’s 36th Infantry Division succeeded in capturing the formidable heights and followed it by blasting San Pietro Infine into rubble, the panzergrenediers began their evacuation on the night of December 16, 1944, completing it by sunup the next day. Escaping capture, the enemy fell back to defensive positions in the vicinity of San Vittore del Lazio, 2 miles/3.2 km to the northwest; they stubbornly held these positions for the next 3 weeks.

The back-and-forth battles for the Bernhardt/Reinhard Line, begun on November 5, and subsequently the village of San Pietro Infine (December 8–17) cost an enormous 16,000 U.S. casualties. German casualties are unknown. Several hundred San Pietro males between 15 and 45, conscripted by the Germans, were brutalized by digging trenches, hauling ammunition, and erecting bullet- and bomb-proof fortifications, mutually supporting pillboxes, and roadblocks for the enemy. Close to 200 would lose their lives due to exhaustion, starvation, the cold, and the savage German and Allied aerial bombing and mortar and artillery shelling that obliterated their town and everything in it. The 10‑day Battle of San Pietro was recorded for the U.S. War Department by Hollywood screen writer and film director John Huston (see video below).

Having seized the subsidiary Bernhardt Line, it took the U.S. Fifth Army until mid-January 1944 to fight its way to the primary line of German defenses, the Gustav Line, anchored by the town of Cassino, which lay to the west of San Pietro Infine. Once at that line the Fifth Army commenced the first Battle of Monte Cassino on January 17, 1944. After the last of 4 engagements at Monte Cassino (mid-January to mid-May) the Germans retired northward, leaving Rome undefended and thus open to the Fifth Army’s occupation on June 5, 1944. Six months later the U.S. Fifth and British Eighth armies merged, becoming the 15th Army Group. Finally defeated in the 15th Army Group’s spring offensive, the Axis forces in Italy surrendered unconditionally on May 2, 1945.

German Winter Line Defenses on the Italian Peninsula and the Battle of San Pietro

|

Above: Taking advantage of the point at which the Italian Peninsula is narrowest, the Germans built their “Winter Line,” which consisted of 3 parallel defensive systems to the south of the Italian capital Rome. The defensive lines were called the Bernhardt Line (also called the Reinhard Line), colored green in this map; the Gustav Line (red); and the Hitler Line (green). Spaced roughly 11 miles/18 km apart, the defensive lines served as a formidable series of obstacles in the path of the Allies’ march toward Rome. The Bernhardt/Reinhard Line was the southernmost of the three and was the German fallback position from the Barbara Line and Volturno Line further to the south as German forces retreated gradually up the peninsula. The Bernhardt/Reinhard Line was actually a southern bulge in the stronger Gustav Line to the north. On the eastern side, the Bernhardt/Reinhard Line bulged south from Cassino to incorporate the mountains overlooking the approaches to the Liri Valley and then moved west to the Tyrrhenian coast. The Bernhardt/Reinhard Line passed directly through the town of San Pietro Infine, blocking the Mignano Gap, the pass through which Route 6, the main Naples-to-Rome highway up the center of Italy, ran toward Cassino and the entrance to the Liri Valley plain.

|  |

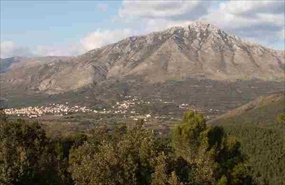

Above: Mt. Sambúcaro overlooking the modern town of San Pietro Infine (left) and ruins of the original town (center). After the war it was decided that the original centuries-old town would not be rebuilt. Instead, a new town arose a few hundred yards/meters to the west. The ruins of San Pietro Infine were left intact and are today a living reminder of tragic events that occurred during World War II in Italy. In 2003, on the 60th anniversary of the Battle of San Pietro, a tall slab memorial was unveiled upon which are inscribed the names of close to 200 townspeople who perished in the battle.

John Huston’s 1945 Documentary, The Battle of San Pietro

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click