ENIGMA, GERMAN ENCRYPTION DEVICE, CODES SEIZED

Bletchley Park, England • May 9, 1941

As war loomed in Europe, British codebreakers based at Bletchley Park outside London worked feverishly to unravel the Enigma cipher machine, which the Germans used to encrypt their most secret communications. The Enigma had a number of differently wired scrambler rotors (aka coding cylinders) that operators changed and shuffled through billions of permutations, making the encoded text infuriatingly difficult to decipher.

In late July 1939, just over a month before the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) attacked Poland, the Poles delivered a Polish-reconstructed Enigma machine, along with details of the equipment, to Bletchley Park. This gift was the springboard that allowed the oddball set of British mathematicians, linguists, and scientists to repeatedly break the far more complicated and thus secure systems introduced after war broke out.

On this date, May 9, 1941, the British retrieved a naval Enigma encoding machine, operating instructions, manuals, codebooks, a stack of messages sent and received, and the rotor settings (encryption keying tables) then in use from a German submarine (U‑110) captured east of Greenland. (Praying that the Germans not find out about the U‑boat’s capture and change all naval codes and the cipher system, the British concocted a story that one of their destroyers had sunk the submarine (actually, the sub was lost 3 days later under tow to Iceland) and decorated the officers and crew for sinking the sub.) Two days earlier codebooks and documents on the operation of another Enigma machine fell into British hands when an enemy weather ship was captured in the North Atlantic. Over a year later another U‑boat’s Enigma machine and the immensely valuable codebooks with all current settings for the encryption key were conveyed to Bletchley Park.

The combination of the 2 May 1941 captured prizes allowed British cryptologists to eventually read the different wartime Enigma codes used by the German army, navy, and air force. Within months intelligence from the decrypts (called Ultra) allowed the Allies to reroute many merchant convoys past U‑boats in the North Atlantic, saving hundreds of lives and hundreds of thousands of tons of vital shipping. It also began to tip the Battle of the Atlantic in the Allies’ favor in that the hunted now became the hunters. In May 1943 alone, 43 enemy subs were sunk, bringing the total to 100 since the start of the year. So great was the stepped-up offensive by Allied submarines and escort carrier- and land-based aircraft that Adm. Karl Doenitz, commander-in-chief of the Kriegsmarine, withdrew his U‑boats from the Atlantic for a time, never to repeat their great victories upon their return. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, whose island population was close to being starved by the U‑boat menace, called cracking the German Enigma code the “secret weapon” that won the war.

Bletchley Park and Decoding the Enigma

|  |

Left: Bletchley Park, top-secret headquarters of Britain’s Government Code and Cypher School, where ciphers and codes of several Axis countries were decrypted. This mock-Tudor mansion, with its surrounding buildings (“huts”), was home to as many as 10,000 men and women during the war, including Britain’s most brilliant mathematical brains, and was the scene of immense advances in computer science and modern computing. Churchill referred to the Bletchley staff as “the geese that laid the golden eggs and never cackled.”

![]()

Right: Alan Turing (standing) was an English mathematician and wartime codebreaker. At Bletchley Park, Turing (1912–1954) took the lead in a team that designed an electromechanical machine known as a “bombe” (Polish, bomba) that successfully broke German ciphers. Turing’s decryption bombe, a forerunner of modern computers, was capable of trying all 17,756 theoretical settings on a 3‑rotor Enigma machine in just 20 minutes. Turing is widely considered to be the father of computer science and artificial intelligence. The commercially and critically successful 2014 film The Imitation Game, starring Benedict Cumberbatch, is loosely based on the role Turing and his cryptanalysts played in solving the Enigma code. On June 23, 2021, the anniversary of his birthday in 1912, Turing became the new face of Britain’s £50 note.

|  |

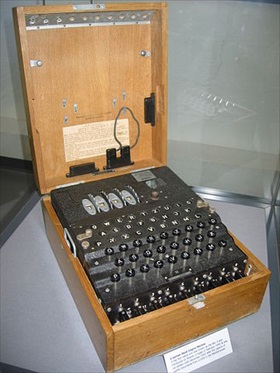

Left: A 4-rotor German naval Enigma encoding machine, 24 inches square and 18 inches high, enclosed in a wooden box on display at Bletchley Park. The combination of the 2 British-captured cryptographic (coding) prizes in May 1941 was crucially important in breaking German U‑boat codes and ultimately in winning the Battle of the Atlantic. One Bletchley Park veteran said that Ultra decrypts shortened the war by 2 to 4 years. America’s version of an electromechanical rotor-based cipher machine was the SIGABA, the U.S. Army’s version of the Navy’s CSP-888/889. The SIGABA, which had 3 banks of 5 rotors each, is less well known compared to the German Enigma machine because it was never cracked, was not so portable (thus, impractical to use in the field), and was not overused.

![]()

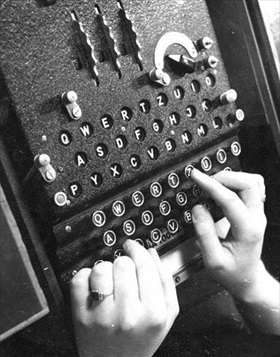

Right: A 3-rotor Enigma machine in use by the Luftwaffe, December 1943. Three major components—26 wires that transmitted an electrical signal that passed through a plugboard and then through 3 scrambler rotors moving independently while enciphering the message—produced an Enigma message that was encrypted 26 times by 26 times by 26 times. A cryptographic analyst would have to press 17,576 letter keys to find the starting point for the original message. Almost to the end of the war, the Germans had firm faith in the Enigma ciphering machine; indeed, Adm. Doenitz had been advised that a cryptanalytic attack on his naval Enigma machines was the least likely of all his security problems. But in fact Allied codebreakers were deciphering nearly 4,000 German transmissions daily by 1942, reaping a wealth of information.

Bletchley Park: Breaking the Unbreakable German Enigma Coding Machine

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click