EISENHOWER SETS GOAL: CAPTURE NAZIS’ NATIONAL REDOUBT

SHAEF HQ, Reims, France • March 11, 1945

The hard-fought victories of the Western Allies between October 1944 and the Rhine River crossings in March 1945 held out the promise of an imminent end to the war in Europe. Seven Allied armies were advancing north, east, and south into the German heartland against bitter albeit diminishing resistance. In the east, the Red Army was closing in on the Nazi capital, Berlin. Spoiling any thoughts of a quick end to combat was the preconception among Western intelligence analysts and strategic planners that the most fanatical elements in Germany’s armed forces and the Nazi Party would make a desperate, tenacious, and prolonged last stand in the likeliest but hardest-to-breach place in the fast-shrinking Reich, namely, the Bavarian, Austrian, and Italian (Tyrolean) Alps.

The notion of a German “last stand” in a National Redoubt, as the stronghold was commonly called, affected the calculus of Allied military commands. Analysts gathered intelligence from Allied spying agencies and Army and Army-Group intelligence (G‑2) sections using conventional means such as reading and listening to German media, photoreconnaissance, unit after-action summaries, and POW and civilian interrogations. More and more, though, analysts and military commands relied on selective, highly secret ULTRA (high-level German radio communications) decrypts supplied by Britain’s Bletchley Park codebreaking team to tease out German intentions and strengths.

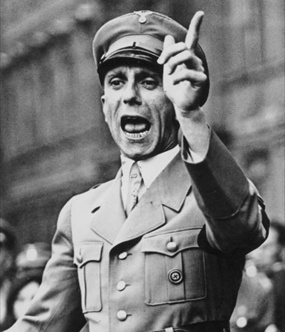

After the war’s conclusion the National Redoubt was revealed to have been a hoax. But during its halcyon days in March and April 1945 the hoax was embraced by Allied higher-ups, particularly at SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force), who were encouraged by none other than Joseph Goebbels. Adolf Hitler’s propaganda minister set up a special unit to deceive SHAEF’s G‑2 division with fake blueprints of defensive fortifications (antiaircraft and other weapons sites) and reports about construction, subterranean armaments facilities, and officer, troop and foodstuff transfers to the Alpine Redoubt that could be (and were) intercepted, decrypted, and passed to those who could act on ULTRA information. ULTRA seemed perfectly believable to actors who, once-burned, twice-shy (see photo essay below), wanted to believe in it.

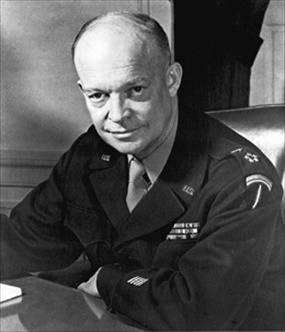

Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower read the SHAEF Weekly Intelligence Summary dated this date, March 11, 1945 (Number 51). It asserted that the Nazi regime’s most important ministries and personalities, including the sinister enforcer of the Nazi state Reichsfuehrer‑SS Heinrich Himmler, Reich Marshal and Luftwaffe chief Hermann Goering, and Hitler, were relocating personnel and perhaps themselves to mountain strongholds south of Munich, the Bavarian capital. Air reconnaissance and successive SHAEF weekly intelligence assessments for March convinced Eisenhower that the Alpine Redoubt was of greater import to Nazi Germany’s defeat than the Soviets’ capture of Berlin. Eisenhower thus shifted the West’s major battleground from Northern Germany to Central Germany, where 3 U.S. armies under Gen. Omar N. Bradley operated.

Successive SHAEF intelligence reports described with rising alarm the perceived trajectory of Germans busily fortifying the Alpenfestung. True, the word “unconfirmed” appeared on SHAEF wall maps and in the weekly summaries. But for the most part thin rumors and overhyped speculation were turned into certainty despite the absence of ULTRA decrypts providing hard evidence about the Redoubt’s defenses. That was clear when Gen. Jacob Dever’s Sixth Army Group burst into the National Redoubt in May and discovered that very few German combat troops had made it to the mountains. In the afternoon of May 4, 1945, the area around Berchtesgaden and Hitler’s bomb-damaged Berghof was easily overrun by elements of Lt. Gen. Alexander Patch’s Seventh U.S. Army. SHAEF’s Weekly Intelligence Summary of May 6 spoke of capturing 460 generals, 7 field marshals, and 1 Reich Marshal, namely Goering. Of the Redoubt’s demise Eisenhower simply said: “The National Redoubt had been penetrated [its officer corps captured] while its intended garrison lay dispersed and broken outside its walls.” Luckily, the Nazis’ final stand turned out to be a dud.

Nazi Germany’s National Redoubt: Dead-End of Hitler’s Third Reich

|

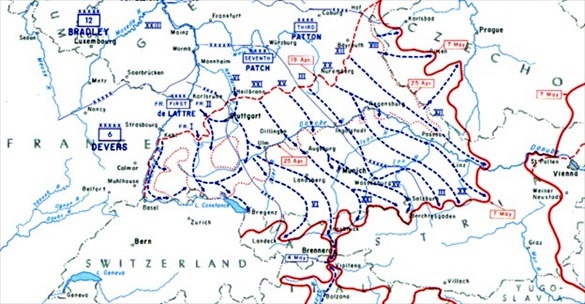

Above: The busy portion of this map depicts the rugged Alpine region of Europe that reportedly included a system of defensive fortifications variously known as the National Redoubt, Alpine Redoubt, Alpine stronghold, and Alpenfestung, the latter term a late entry in the list of monikers that referred to the same Alpine location. The dashed lines represent the routes of Allied armies that ended the short-lived existence of the National Redoubt in May 1945. The National Redoubt’s existential roots date to at least late 1944, when an article, “Hitler’s Hideaway,” in the New York Times Magazine on November 12, 1944, described an impregnable fortress under construction in the Berchtesgaden area (center and above the wiggly east-west red line in this map). The mountainous terrain was allegedly full of bombproof caves and tunnels stuffed with food and military supplies—the perfect place for fugitive Nazi big shots, ideologues, and hard-line Nazi zealots to engage in a protracted, eleventh-hour fight to the end and to die like heroes in a modern-day Wagnerian Goetterdaemmerung. The next month the U.S. War Department, SHAEF, and international media began referring to these defensive fortifications as the National Redoubt.

|  |

Left: Adolf Hitler’s bombastic propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, saw the potential value of a National Redoubt to a desperate Wehrmacht (German armed forces). Increasingly the Wehrmacht was on the back foot in the last year of war, needing relief in a plausible distraction like a National Redoubt hoax until such time as the country’s army and air force’s wonder weapons could reverse Germany’s sagging military fortunes. For his part Hitler appreciated the hoax’s distractible value but pooh-poohed establishing an impregnable mountain stronghold for organized last-ditch resisters in the backyard of his heavily guarded, split-level Berghof country mansion/mini-chancellery on the 6,700‑ft Obersalzberg near Berchtesgaden. Even to talk about a redoubt smacked of defeatism, he would snap.

![]()

Right: Eisenhower had been badly burned by previous G‑2 missteps. The Allied debacle at Kasserine Pass in North Africa in February 1943 (Operation Torch) and the surprise Ardennes Offensive in late 1944/early 1945 (Battle of the Bulge) were costly lessons about the importance of good and timely intelligence. By Spring 1945 Eisenhower was taking no chances when it came to shortening the war by tolerating a possible hornet’s nest of German fanatics acting out Hitler’s public vow never to surrender.

|  |

Above: ULTRA provided proof in April 1945, the final month of war, that Hitler’s regime was separating its main military headquarters—one staff in the north, one in the south. Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz (left frame) moved his headquarters from Berlin on April 22 to (eventually) Muerwik near the Danish border. As Oberbefehlshaber Nord (Commander-in-Chief, North) Doenitz assumed military and civilian affairs in Northern Germany. He briefly served as President of Germany following Hitler’s suicide. Doenitz spent 10 years in a West German prison following his 1946 conviction as a war criminal by the International War Tribunal at Nuremberg, Germany. He died in December 1980. Field Marshal Albert Kesselring (right frame), lately Commander-in-Chief West and anointed Oberbefehlshaber Sued (Commander-in-Chief, South), moved to (eventually) Strub near Berchtesgaden, the picturesque village below Hitler’s Berghof in Upper Bavaria about the same time. He assumed military and civil responsibilities for Southern Germany. Kesselring surrendered to the U.S. Army near Salzburg, Austria, on May 9, 1945. In 1947 a British military court sentenced him to death for his wartime activities in Italy as Oberbefehlshaber Suedwest (Commander-in-Chief, Southwest). His sentence was commuted and he died in 1960.

Author Rick Atkinson Explains Eisenhower’s Interest in Eliminating Germany’s National Redoubt (Skip first 30 seconds)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click