EARLY RUSSIAN WINTER UPSETS BLITZKRIEG SUCCESS

Moscow, Soviet Union • October 15, 1941

On June 22, 1941, the day Adolf Hitler sprang his surprise attack on the Soviet Union, a country of 180 million people to Germany’s east, he reportedly confided to some of his intimates: “I feel as if I have opened a door into a dark, unseen room—without knowing what lies behind the door.” His gloomy premonitions soon gave way to glee as intoxicating reports of military victories came across the news wires. Advancing German armies occupied vast stretches of the Baltic States in the north, the Ukraine on the Black Sea in the south, and Belarus in between. At a press briefing in Berlin on October 10, 1941, Hitler’s press chief, following a meeting with his boss the day before on the Eastern Front, released the first substantial news about Operation Barbarossa. The very last remnants of the Red Army, Otto Dietrich told journalists, were locked in two German steel pockets before Moscow, the Soviet capital, and were undergoing swift, merciless annihilation. The road to Moscow for German panzer (armored) armies was now open, the war was as good as over in Hitler’s mind (Hitler issued a chest-thumping proclamation to the troops expressing these sentiments), and the German high command’s nightmare of a two-front war in the West and East was swept from memory.

The German conquest of Russia would allegedly add more manpower at Germany’s disposal than all the manpower available to Great Britain, North America, and South America combined—a very disturbing development were it to be realized. Ominously, however, for the war planners at Hitler’s remote dream world, “Wolf’s Lair” (Wolfsschanze) in Rastenburg’s forests in East Prussia (today’s Polish village of Kętrzyn), where the Fuehrer was busy directing military operations now far from the front, the first heavy snowfalls of the Russian winter were recorded on this date, October 15, 1941. Shortly thereafter a premature, unusually bitter arctic winter set in. The Wehrmacht (German armed forces) had counted on at least four additional weeks of mobility in their drive eastward. Instead their armies were frozen in place, and the earlier October prophecy of a war as good as won was shelved for now to Hitler’s undying embarrassment.

The Battle of Moscow (October 1941 to early January 1942), named by the Germans “Operation Typhoon,” was intensified as Red Army forces from the Soviet Far East and Siberia began arriving on the Russian Front. (Soviet spy Richard Sorge in Tokyo assured his Moscow handlers that Hitler’s Axis partner Japan had no intention of attacking the Soviet East; instead, the Japanese were preparing to launch a massive offensive into Southeast Asia and the Pacific, which they did on December 7 and 8, 1941.) Early in December a single German battalion snow-shoveled close enough to Moscow to glimpse the golden spires of the Kremlin. But that was as near as any Wehrmacht unit got before withdrawing behind German lines, where fuel froze (temperatures sank to 36°F below zero), machine guns ceased firing (bolts stuck), vehicle hoses and belts cracked and broke, and ill-clad soldiers died from severe frostbite or were invalided temporarily to the rear, reducing the strength of a typical combat company to that of a squad. Hitler’s vague hope that Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin would come to realize the hopelessness of further resistance, would abandon European Russia to Nazi Germany, and would content himself with a country east of the Ural Mountains was swept away by frigid typhoon-force winds now blowing in his face.

![]()

German Invasion of Soviet Union Stopped Cold by 1941 Russian Winter

|

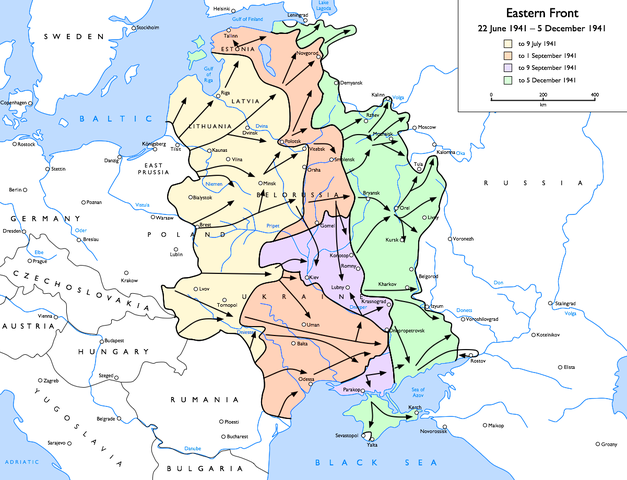

Above: Map of German operations against the Soviet Union, June 22 to December 5, 1941. Occurring in three stages, each weaker than the one before, Operation Barbarossa was the largest military operation in history in terms of manpower, casualties, and prisoners of war (four million Soviet POWs). Hitler formalized the end of Operation Barbarossa in Fuehrer Directive No. 39, issued on December 8, 1941.

|  |

Left: On October 19, 1941, Soviet officials declared their capital and the country’s largest city to be in a “state of siege.” That month almost two million men and three of Germany’s four panzer groups manned the German frontline west of Moscow. Armed with heavy shovels, a hastily assembled work force of Moscow women, teenagers, and elderly men gouge a huge tank moat out of the earth to halt German panzer units advancing on the city. In a feverish effort, some 250,000 citizens labored from mid-October until late November digging ditches and building other obstructions on Moscow’s outskirts. When completed, the ditches extended more than 100 miles.

![]()

Right: Muscovites installed antitank barricades on city streets in October 1941. Between October and the end of November, the capital remained within reach of German panzers, which never came. If they had, dynamite charges, which had been placed in all important buildings, including the Kremlin, would have left the Germans mostly gazing at piles of smoking rubble. The city was, however, the object of massive German air raids, though these caused only limited damage owing in part to extensive antiaircraft defenses and effective civilian fire brigades, as well as to the evacuation of factories, government offices, and people hundreds of miles to the east. By the end of 1941 Moscow’s population had been reduced by half.

|  |

Left: In the wake of autumn rains, German soldiers struggle to pull a staff car through heavy mud on a Russian road, November 1941. Hitler, arrogant and ruinously overconfident owing to his blitz of successes in Western Europe, expected a victory in the East within a few months, and therefore he did not prepare his armed forces for a campaign that might last into a wet late fall, much less a bitterly cold winter. The assumption that the Soviet Union would quickly capitulate—Hitler had promised his generals that a single campaign would crush “the rotten edifice of bolshevism”—proved to be his, as well as the Wehrmacht’s, tragic undoing.

![]()

Right: On December 2, 1941, the first blizzards of the Russian winter began just as one unit of the Wehrmacht caught a glimpse of the spires of Moscow’s Kremlin 15 miles away. That same day a reconnaissance battalion crept to within 5 miles of Moscow, but that was as close to the military prize as any Wehrmacht unit managed. In this photo a Panzer IV tank in white camouflage is stranded in deep Russian snow as its crew attempts to free it. At the right edge of the photo is a war correspondent who filmed the scene for audiences back in Germany.

|  |

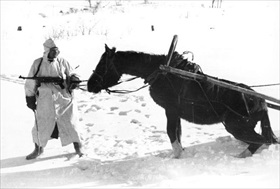

Left: A German soldier with machine-pistol and white winter coat tugs at a horse pulling a cart in snow-covered landscape west of Moscow. Horse-drawn supply transports as well as combat units were equally stopped first by autumn mud, then by deep winter snow. Heinz Guderian, commander of the German Second Panzer Army, wrote in his journal: “The offensive on Moscow failed. . . . We underestimated the enemy’s strength, as well as his size and climate. Fortunately, I stopped my troops on 5 December, otherwise the catastrophe would be unavoidable.” By coincidence, the Soviets launched their counteroffensive on the very day that the German high command called a halt to Operation Barbarossa. For his efforts to avoid catastrophe and his sanctioning unauthorized pull-backs Guderian, along with 40 other generals, was relieved of his command on December 26, 1941.

![]()

Right: Two German soldiers in heavy snow on guard duty west of Moscow, December 1941. December’s low temperature reached –20°F. More than 130,000 cases of frostbite were reported among German soldiers, most of whom lacked winter uniforms. The unforgiving weather hit Soviet troops, too, but they were better conditioned and equipped for the deadly cold, particularly those who had been rushed in from Siberia to defend the capital. Many had proper winter boots, heavy jackets and overcoats, and white camouflage coverings. All this proved an increasingly critical factor in the Battle of Moscow as more and more ill-clad, freezing, and exhausted German soldiers were being captured or were surrendering to the Soviet enemy.

Color Footage of Battle of Moscow, October 1941 to January 1942. (Footage switches between combatants. You may want to mute the music.)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click