DECISION TIME FOR JAPAN—HIROHITO

Tokyo, Japan · August 12, 1945

In 1945 the endgame in Europe was to take Berlin, the epicenter of Nazi resistance, which the Red Army did in the last week of April. On May 7 and 8, 1945, Adolf Hitler’s political heir, Adm. Karl Doenitz, surrendered Nazi Germany unconditionally to the Allies. The endgame in the Pacific War seemed to be the incineration of Japan. As President Harry S. Truman said on August 6, following the atomic bombing of Hiroshima: “We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city.”

On this date in 1945 in Tokyo, Japanese Emperor Hirohito (posthumously referred to as Emperor Shōwa) informed his family of his decision to order his country’s surrender to the Allies. Until August 9, the Supreme Council for the Direction of the War had set four preconditions for Japan’s surrender. But on this day the emperor ordered his Lord Privy Seal to “quickly control the situation” in light of the Soviet Union’s entry into the war on August 9. (August 9 was also the date the U.S. dropped a second atomic bomb on Japan, this on the city of Nagasaki. A third bomb was being readied for delivery on August 17 or 18.) Then Hirohito held an Imperial conference that included both the war council and the entire cabinet during which he authorized Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō (the same person who had signed the declaration of war on the U.S. in 1941) to notify the Allies that Japan would accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration of July 26, 1945 (“unconditional surrender” over “prompt and utter destruction”) on one condition: that surrender did not compromise the prerogatives of the emperor as a sovereign ruler.

The Allies’ August 11 response (it was August 12 when it arrived in Tokyo), known as the Byrnes Note after the U.S. Secretary of State who crafted it, seemed to leave intact the principle of the preservation of the Throne: “The ultimate form of government of Japan shall, in accordance with the Potsdam Declaration, be established by the freely expressed will of the Japanese people.” It was a condition Hirohito could live with: “I think the [U.S.] reply is all right,” the emperor told his foreign minister. “You had better proceed to accept the note as it is.” And so on August 14 Hirohito recorded Japan’s capitulation announcement that was broadcast to the nation the next day, August 15. Speaking frankly to his subjects Hirohito acknowledged the awesome loss of life and destruction of property caused by two atomic bombings and the potential for more of the same, saying, “Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.” After the broadcast the emperor’s war cabinet resigned en masse.

The Inescapable Annihilation or Unconditional Surrender of Japan, August–September 1945

|  |

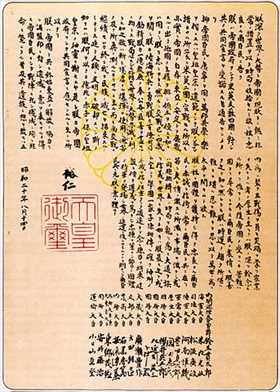

Left: Emperor Hirohito’s Rescript on the Termination of the War. The rescript was written on August 14, recorded on a phonograph record, and broadcast to Japanese citizens at noon on August 15, 1945. Hirohito’s Gyokuon-hōsō (lit. “Jewel Voice Broadcast”) made no direct reference to Japan’s surrender or defeat. Neither did it contain the words “apologize” or “sorry.” Instead, the emperor said he had instructed his government to accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration fully. This circumlocution confused many listeners who were not sure if Japan had surrendered or if the emperor was exhorting his subjects to resist an enemy invasion. The poor audio quality of the radio broadcast, as well as the formal courtly language in which the speech was delivered, added to the confusion.

![]()

Right: Recently appointed Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu, along with Army general and Supreme War Council member Yoshijirō Umezu, signs the Japanese Instrument of Surrender on board USS Missouri as Gen. Richard K. Sutherland and Toshikazu Kase, a high-ranking Japanese Foreign Ministry official, watch. Tokyo Bay, September 2, 1945. Both Shigemitsu and Umezu were tried as war criminals at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo and imprisoned.

Footage of the Moment the Japanese Surrendered Aboard the USS Missouri

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click