“DAMBUSTERS” BREACH RUHR DAMS

London, England • May 16, 1943

At least since 1937, 2 years before the outbreak of European hostilities, British intelligence had looked into developing alternative ways to destroy German factories in the Ruhr Valley, Germany’s industrial heartland. One suggestion was to attack dams in the Ruhr region. The idea was to blow up the dams or strike them with bombs to create breaches that would cause catastrophic flooding. Late on this date, May 16, 1943, a Royal Air Force squadron of 19 modified Avro 4‑engine Lancaster Mk.III heavy bombers, each with a 9,250 lb./4,196 kilograms payload of 1 externally mounted, specially designed “bouncing bomb” (actually a revolving depth charge codenamed Upkeep), flew toward 3 dams on the Moehne and Eder rivers in the Ruhr Valley.

The “dambusters” in Operation Chastise dropped their bombs into the reservoirs when spring runoff was at its highest.The barrel-shaped bombs, released without the aid of a bombsight or altimeter from a height of 60 feet—this while traveling at 220 mph—skipped across the water’s surface like stones ricocheting across a lake, to sink and detonate against the face of the dam at a predefined depth. (Fitted with electric motors to set them spinning backwards to the direction of travel before being released, the bombs needed to skip over the water to avoid being trapped in protective antitorpedo steel netting near the wall; spinning backwards ensured that the bombs hugged the wall when they hit it and sank.) Three hydrostatic fuses detonated the thin-skinned bombs some 30 feet/9.1 meters below the surface and the shock waves of 6,600 lb/2,994 kilograms of Torpex explosive (50 percent more powerful than TNT by mass) punched huge holes in the dams, causing large portions of the walls to collapse.

The spectacular feat of precision bombing, arguably the most audacious bombing raid of the European war, breached 2 of the 3 targeted dams. The Moehne dam alone spilled around 330 million tons of water (87 percent of its reservoir) into the western Ruhr region, devastating factories, homes, mines, bridges, roads, pumping stations, and farmland for miles/kilometers around. Some farmland remained effectively unusable until the 1950s. The loss of the 2 dam power plants and the destruction of 7 others interrupted hydroelectric power generation for about 2 weeks. The greatest impact was felt, as intended, on the Ruhr’s munitions industry. German leader Adolf Hitler dispatched 7,000 workers to clean up the damage and begin rebuilding the dams. He also approved the transfer of an additional 20,000 workers, many from Atlantic Wall projects, to assist with the dam repairs, which were completed 5 months later for a loss of as little as 5 percent of armament production in the latter half of 1943. Strangely, the RAF, at a cost of 8 Lancasters and 53 crew members in the Chastise raid, did not return to bomb the dams as they underwent repairs.

Bodies of at least 1,579 victims were found along the Moehne and Ruhr rivers, with hundreds of people gone missing. The city of Neheim was worst hit: over 800 people perished, among them some 500 female slave laborers from the Soviet Union. The drowning of thousands of civilians and POWs led to changes in the Geneva Convention to prohibit similar raids in the future “if such may cause release of dangerous forces from the works or installations and consequent severe losses on the civilian population.”

Operation Chastise: Busting Dams in Germany’s Industrial Heartland

|  |

Left: A practice 10,000 lb./4,536 kilogram barrel-shaped bouncing bomb attached by V‑shaped caliper arms to the bomb bay area of Wing Commander Guy Gibson’s Avro Lancaster, at Manston, Kent, while conducting dropping trials at the Reculver bombing range. Only 1 test with a live bomb ever took place, this 3 days before Operation Chastise kicked off. To reduce weight and drag, the Lancaster’s mid-upper gun turret was removed, the hole covered, and the bomb bay doors removed. The deficit of a missing bombsight was made up by hand-held, triangular pieces of wood with a sighting hole at the apex. The opposite base had nails in various points that when lined up with the dam’s 2 sluice towers fixed the release point for the bomb. Determining the 60 ft. height on account of the missing altimeter were 2 angled Aldis spotlights, 1 installed in the nose and the other behind the bomb bay to create a figure eight pattern that could be seen by the bombardier in front of the starboard wing.

![]()

Right: Movie still, showing an inert, practice version of the bouncing bomb being dropped during a training flight by members of RAF 617 Squadron at Reculver bombing range, Kent. The bomb’s ingenious designer, Barnes Wallis, and others watch the practice bomb strike the shoreline.

|  |

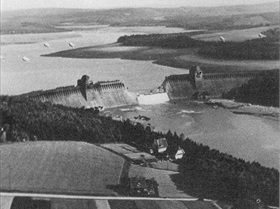

Left: The Moehne dam breached, photographed by an RAF pilot on May 17, 1943, 1 day after RAF 617 Squadron had attacked the dam with their cylindrical bombs. Six barrage balloons can be seen above the dam. The 2 direct hits on the concrete-and-steel gravity Moehne dam resulted in a breach around 250 ft. wide and 292 ft. deep. A torrent of water around 32½ ft. high and traveling at around 15 mph swept through the valleys of the Moehne and Ruhr rivers in North Rhine-Westphalia, extending for around 50 miles/80 kilometers from the source.

![]()

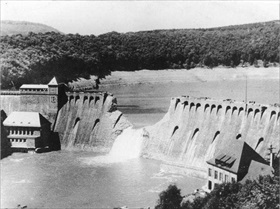

Right: After numerous runs along the length of the Eder dam, the largest in Europe, the Chastise Lancasters managed to breach the dam in 2 places, causing the dam to release 75 percent of its contents. The wave from the breach was not strong enough to result in significant damage by the time it reached Kassel, the largest city in Northern Hessen, some 22 miles/35 kilometers downstream. The crest of a third dam, the Sorpe dam, had a portion blown off—this after 10 runs—but was otherwise unscathed, protected from the Lancasters by an increasingly dense fog that rolled in during the raid.

Dambusters Declassified Documentary: Retracing the Legendary 1943 Raid by RAF 617 Squadron

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click