D-DAY HERO TEDDY ROOSEVELT, JR., LAID TO REST

Sainte-Mère-Église, Normandy, France • July 14, 1944

On this date, Bastille Day in France, the U.S. Army laid to rest Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., at the U.S. cemetery in Sainte-Mère-Église a few miles/kilometers west of Utah Beach in Normandy. The 56‑year-old Roosevelt had died of a heart attack less than 2 days before at Méautis, a village 12 miles/19 kilometers south of the first of 2 burial sites where his body was interred and 13 miles/21 kilometers from Utah Beach, where he and men of the 4th Infantry Division landed 37 days before, on D‑Day, June 6, 1944. Among Roosevelt’s honorary pallbearers were Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, Commander of First U.S. Army and Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., Commander of the not-yet-activated Third U.S. Army.

Son of the 26th president of the United States (1901–1909), Roosevelt had close to 3 decades of political and military experience before his death. He served in office under one state governor (New York), 4 presidents, one with whom he shared a distant relationship (Franklin D. Roosevelt), and was a veteran of 2 world wars. During the interwar years he served in the Army reserves. With the outbreak of World War II in Europe the 50‑year-old Roosevelt returned to active duty rising to the rank of 1‑star general with the 1st Infantry Division, the Big Red One.

Earning a reputation as a hard-fighting frontline general during Operation Torch (1942–1943) in North Africa and the Italian Campaign (July 1943 to May 1945) that followed—in both undertakings winning the esteem and admiration of the units he commanded—Roosevelt petitioned First U.S. Army commander Bradley for a combat role in the planned invasion of Northern France, Operation Overlord. In February 1944 the scrappy, 5‑foot 8‑inch tall general was ordered to England and made assistant commander of the untried 4th Infantry Division, the Ivy Division, Maj. Gen. Raymond O. Barton commanding. To Bradley’s way of thinking, if Roosevelt went in with the leading wave, he could steady the greenhorn soldiers as no other man could owing to the gutsy warrior’s immunity to fear. Bradley didn’t hold back his own fear, warning Roosevelt, “You’ll probably get killed on the job.” Barton initially voiced misgivings about Roosevelt being in the assault wave as well but withdrew them.

When the Higgins boat carrying Roosevelt and E Company, 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment hit Utah Beach early on June 6, Roosevelt was the first one off the landing craft. Roosevelt looked for landmarks he expected to find, only to determine that the first assault wave was over a mile/1.6 kilometers east of the 4th Infantry Division’s designated landing spot. He became a D‑Day legend when he exclaimed: “We’ll start the war from here!”

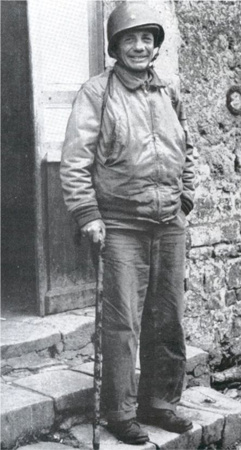

Bradley’s prediction was spot on that Roosevelt would be an inspiration to his green troops. Leaning on his ever-present cane and wearing his trademark grin, Roosevelt prowled much of the 3 assault sectors, shrugging off the defenders’ automatic weapons and field artillery fire while urging his men to hasten up the sandy beach dunes, ford the flooded low-lying areas behind the landing areas, and make contact with 101st Airborne paratroopers to the rear. That happened by noon. By end of the first day the 4th Division had pushed inland about 4 miles/6 kilometers). Ironically for an assault that began in error, the Utah Beach landings ended the day in spectacular fashion: 20,000 troops and 1,700 vehicles were on French soil at a cost of fewer than 300 casualties.

Roosevelt spent his last full day, June 11, 1944, at the front. Later that day he was visited by his son, 24‑year-old Captain Quentin Roosevelt II. The junior and senior Roosevelts were the only father-son team to land in Normandy on D‑Day. Quentin spent 2½ hours conversing with his father before taking his leave. After Roosevelt had crawled into a converted sleeping truck captured from the Germans, the general was stricken with chest pains about 10:00 p.m. He was quickly surrounded by medical help, dying around midnight, June 12, 1944, of a heart attack.

Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., at Utah Beach, June 6 to July 14, 1944

|  |

Left: Throughout that “longest day” Roosevelt did his level best to steady the nerves of scared, wet young soldiers who had never seen combat until D‑Day, June 6, 1944. The assistant commander of the 4th Infantry Division was all over Utah Beach. He scouted for causeways behind the beach sectors for the division’s push inland. He directed regiments to their changed objectives. He personally led a group of soldiers in a charge over a seawall, established them inland, and then returned to the beach to orchestrate more incoming men and materiel. He helped untangle traffic jams of armor and trucks all struggling to move inland from the water’s edge. When Bradley was asked several years later to name the single most heroic action he had seen in combat, he summed it up in 5 words: “Ted Roosevelt on Utah Beach.” Roosevelt’s masterful leadership at Utah Beach was recalled by Cornelius Ryan in his 1959 classic bestseller, The Longest Day. He was portrayed by Henry Fonda in Darryl F. Zanuck’s 1962 blockbuster of the same name.

![]()

Right: On the day of Roosevelt’s death, midnight June 12, 1944, Bradley had selected the 1‑star general for promotion to the 2‑star rank of major general with command of the 90th Infantry Division. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, approved the assignment, but Roosevelt died the day before he was to assume his new command and before his battlefield promotion could be awarded. “The Lion is dead,” Quentin wrote his mother on June 12. The funeral service was conducted in the official cemetery at Sainte-Mère-Église, a few miles/kilometers west of Utah Beach. Roosevelt had a fibrillating heart condition and troublesome arthritis linked to his World War I injuries that forced him to use a cane. He kept his heart condition secret from army doctors and his superiors.

|  |

Above: Lt. Gen. Patton wrote in his diary that Teddy Roosevelt, Jr., was the bravest soldier he ever knew. Bradley agreed: “I have never known a braver man nor a more devoted soldier.” Both generals were among the 10 generals who volunteered to be Roosevelt’s honorary pallbearers (left frame). They included Maj. Gen. Barton, Roosevelt’s senior officer in the 4th Infantry Division; Lt. Gen. Clarence Huebner, former commanding general of the 1st Infantry Division to which Roosevelt had once been attached; Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges, deputy commander of Bradley’s First Army; and Maj. Gen. J. Lawton “Lightning Joe” Collins, who forced the surrender of the strategic Normandy port of Cherbourg where Roosevelt had briefly served as military governor. Collins appears in the right frame, goggles on his helmet, partially hiding Patton (dark uniform), while Bradley stands in the center of the group of generals. Interestingly, a passerby with a Leica camera and collapsible 3.5 Elmar lens, Army Pfc. Sydney Gutell, stopped by the cemetery known colloquially as Jayhawk cemetery. For 53 years Gutell had no idea whose funeral it was, nor who the attendees were apart from Bradley and Patton, and snapped the only photos of Roosevelt’s burial.

Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., 1887–1944, a Short Autobiography Read by Roosevelt’s Grandson

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click