CRISIS TALKS COLLAPSE, POLAND MOBILIZES ARMY

Warsaw, Poland • August 30, 1939

After his sudden decision on Friday, August 25, 1939, to cancel his invasion of Poland, Adolf Hitler ordered preparations for a second planned invasion of his neighbor to the east. From the Army’s Quartermaster General he learned that the earliest date on which mobilization could be completed was Thursday, August 31. Therefore, he set Friday, September 1, as the new launch date. Between those 2 Fridays, Hitler and his foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, used every occasion to reassure their inner circles that Great Britain and France would not come to Poland’s aid in the event of war, even though all 3 nations were in, or soon would be in as in the case of France, a military alliance with Poland. Hitler’s fatal miscalculation was due in part to his perverse and reckless faith in force of arms and to Ribbentrop’s repeated assurances that neither Britain nor France was in a position to wage war against Germany, that the 2 nations were only bluffing in order to frighten Hitler out of his plans to attack Poland.

During those days of peace Hitler continued his diplomatic press of isolating Poland from its Western backers. The German offer to meet a Polish plenipotentiary in Berlin to resolve the German-Polish dispute over the fate of the ethnic German enclave of Danzig and the ethnic German minority living in the Polish Corridor was rejected by the Poles. (Both populations had formerly been part of West Prussia and the Imperial German province of Posen (Polish, Poznań) but now were cut off from the Reich by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles.) The Poles saw through Hitler’s attempt to overawe the Polish delegation in the German capital, so the Polish Foreign Office recommended a meeting, perhaps in a railway car, in a small town somewhere near the Polish-German border. The next day, Wednesday, August 30, the Polish ambassador, Jóżef Lipski, was shown the door by Ribbentrop for arriving at his office without the requisite plenipotentiary credentials required to negotiate terms.

Ribbentrop, a former German ambassador to London who had alienated much of the British populace with his arrogance, treated Britain’s ambassador, Sir Nevile Henderson, worse. The 2 men came close to blows when Henderson, crimson faced, hands shaking, finger wagging, realized that his country had been duped all week long as Ribbentrop read aloud, in an angry and scornful voice Henderson recalled, a new list of demands on Poland but refused the ambassador’s request to forward it to London or even Warsaw. (The Polish embassy and government were never presented with the latest German demands for new plebiscites on the future of the Polish Corridor and of the former German territories in Western Poland, which at roughly 12 percent of Polish territory and over 3 million people, clearly had the potential to break up the Polish state.) Henderson left the tense meeting convinced that the last hope for peace had vanished.

In Warsaw, on this same date in 1939, Polish authorities announced a general mobilization when it became clear that genuine dialog with Germany was pointless. The see-saw week of diplomatic highs and lows had cost the Polish Army valuable time in preparing for the overdue German invasion of their country, which occurred on Friday, September 1.

Polish and British Ambassadors Who Sought a Peaceful End to the Polish Crisis

|  |

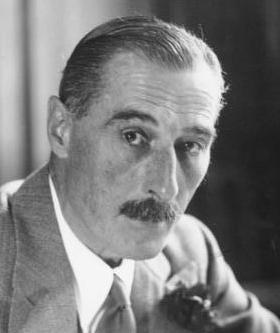

Left: Ambassador Jóżef Lipski, Polish diplomat in Germany, 1933–1939. Poland’s foreign minister, Jóżef Beck, selected Lipski to negotiate for Poland during the week running up to the invasion of that country. Lipski was not the Polish plenipotentiary German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop had demanded to meet with on August 30, 1939. The Poles were dead set against negotiating a solution to the Polish crisis while meeting in the lion’s den; instead, they sent Ambassador Lipski, who lacked the requisite credentials, to feel out the Germans.

![]()

Right: Sir Nevile Henderson, British ambassador to Germany from 1937 to 1939, believed Hitler could be manipulated into embracing peace and cooperation with the Western powers. An hour-long, face-to-face meeting on August 28, 1939, between Henderson and Hitler was “unsatisfactory” in the opinion of Otto Dietrich, Hitler’s press chief, who speculated that the British diplomat had reiterated His Majesty’s Government’s pledge to fulfill its obligation toward Poland. On the fateful night of August 30, 1939, Ribbentrop presented Henderson with Germany’s “final offer” at resolving the Polish crisis, warning him that if Germany received no reply by dawn the ”final offer” would be considered rejected. Several days later it was Henderson who, on the morning of September 3, 1939, 2 days after the German invasion of Poland, delivered the British ultimatum to Hitler, declaring that if hostilities between Germany and Poland did not cease by 11 a.m. that day a state of war would exist between the 2 countries. Germany did not respond and British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain declared war on Germany at 11:15 a.m.

U.S. War Department Uses German News Coverage to Document the Invasion of Poland

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click