CRISIS DECREE SUSPENDS KEY CIVIL RIGHTS

Berlin, Germany · February 28, 1933

On this date in 1933, with the Reichstag (German parliament building) still smoldering following the fire set by 24-year-old Dutch Communist Marinus van der Lubbe the day before, German Chancellor Adolf Hitler persuaded 87-year-old President Paul von Hindenburg to sign the Reichstag Fire Edict. The emergency decree suspended key civil liberty sections of Germany’s Weimar constitution, among them the right to free expression of opinion, including a free press, and freedom of assembly and association. The signature of the ailing, senescent Hindenburg quickly converted Germany from a parliamentary democracy led by a would-be dictator into an absolute totalitarian state. It happened so fast—in less than a month. With parliamentary elections scheduled for March 5, five days away, Hitler, who had dissolved parliament two days after being named chancellor on January 30, ordered the arrests of thousands of opposition Communists, including the party’s head, and rank and file Social Democrats, whose leadership had already fled to the safety of the Czech capital, Prague. Hitler’s paramilitary SA (Sturmabteilung, or “Storm Detachment”) goons, nicknamed “brownshirts,” wreaked havoc everywhere they could, breaking into homes and business all across the country and beating and torturing the victims they dragged out and jailed. On March 5 Nazi organizations “monitored” polling places. Despite their best efforts to emasculate and intimidate their opponents, the Nazis failed to gain an absolute majority of the 39.6 million votes cast, garnering just under 44 percent to control 288 seats in the Reichstag; the Nazis needed the conservative German National People’s Party, which had 52 seats as well as posts in Hitler’s coalition cabinet, to govern the country. To formally and legally place the whole power of government in his hands, Hitler on March 23 urged the Reichstag to enact and Hindenburg to sign the Enabling Act (Ermaechtigungsgesetz). The act, known formally as Law to Remedy the Distress of the People and the Nation, granted Hitler’s cabinet the authority to enact laws without the participation of the Reichstag or his coalition partners. Thus using the tools of parliamentary democracy, Hitler gained unrestricted freedom to ban all political parties except his own and to terrorize, arrest, beat, imprison, torture, and kill any and all of his opponents.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”0199322325,1845456807,0156027542,0674350928,0192802062,0531056333,030680915X,0520253833,0312454686,143919100X” /]

Tightening the Nazis’ Grip on Germany, February and March 1933

|

Above: Before the Reichstag burned: Joseph Ferdinand Klemm’s painting of the German Reichstag and the Bismarck Memorial in the Koenigsplatz (“Square of the King”), Berlin, 1910. After the fire Reichstag members met in the Kroll Opera House (Krolloper), at the opposite end of Koenigsplatz, which is now a large grassy expanse called Platz der Republik (“Square of the Republic”). Both the Bismarck Memorial and Kroll Opera House are gone.

|  |

Left: Tasked with keeping peace and order on election day, March 5, 1933, a Berlin policeman and a Nazi SS (Schutzstaffel) Hilfspolizist (literally, “helpful policeman”) walk the streets of the capital. These March elections were the last freely contested elections held until the collapse of Hitler’s Third Reich in May 1945. Between early March and mid-July 1933, Hitler banned all political parties except his own Nazi Party, formalizing the ban on July 14 by promulgating a law making the Nazi Party the only legally permitted party in the country.

![]()

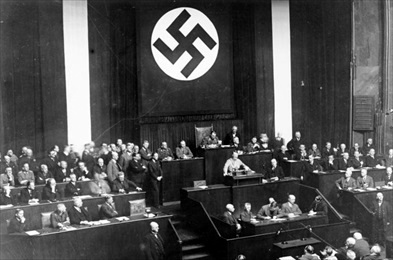

Right: Hitler speaking to Reichstag members prior to their “disempowering” themselves by passing the Enabling Act on March 23, 1933. In part because Hitler’s Brownshirts swarmed inside and outside the Reichstag chamber, the bill met little resistance. The final vote was 444 supporting the Enabling Act to 94 opposed (all center-left Social Democrats). By then the Communist Party (the third largest party in the March 5 elections) had been banned and 26 SPD (Social Democrat) deputies had been arrested or were in hiding. From that date on, the defanged Reichstag only met intermittently until the end of the war, held no debates, enacted few laws, and mainly served as a stage for Hitler’s set piece speeches. Since 1992 a memorial to 96 Reichstag members murdered by the Nazis between 1933 and 1945 has a place of prominence next to the rebuilt Reichstag. The murdered members were chiefly Communists (42) and Socialists (40), and their murders took place in concentration camps such as Sachsenhausen (11), Buchenwald (8), Bergen-Belsen (7), Dachau (7), Ravensbrueck (4), and Mauthausen (4), to name the better known camps.

From Reichstag Fire, February 27, 1933, to the Enabling Act, March 23, 1933, and Its Immediate Consequences (You May Want to Mute the Horst Wessel Song [aka “Die Fahne hoch”], the Nazi Party’s Anthem)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click