CONGRESS APPROVES WOMEN’S AUXILIARY ARMY CORPS (WAAC)

Washington, D.C. • May 14, 1942

Early in 1941 Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts informed Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall that she intended to introduce a bill in the U.S. Congress to establish a volunteer women’s Army corps, separate and distinct from the existing Army Nurse Corps. After long debate—and after the nation had been sucked into fighting a global war on multiple fronts—Congress passed the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) bill on this date, May 14, 1942. Signed into law the next day by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the new women’s Army corps had many weaknesses, among them lack of equal pay with servicemen of similar rank (indeed, the names of equivalent ranks differed), no government life insurance, and no pension, disability, or death benefits available to U.S. military veterans. These weaknesses were removed on July 3, 1943, when the Corps, which hitherto had worked with the U.S. Army, was integrated directly into the Army and the name “Auxiliary” dropped.

Originally the WAAC’s recruitment goal was set at 25,000. Six months later it was revised to 150,000. By then enlisted women were replacing male clerical workers, switchboard operators, and motor pool drivers, all of whom were needed elsewhere in the armed forces. After basic Army training, servicewomen often entered the workforce in non-traditional roles: mechanic, armorer, sheet metal worker, aerial photograph or map analyst, radio operator and repairman, airport control tower operator, and cryptographer. The Army Air Forces obtained 40 percent of all WAACs/WACs and by January 1945 just 50 percent of their servicewomen held traditional assignments such as file clerk, typist, and stenographer. Army Service Forces received 40 percent of all WAACs/WACs, who worked as draftsmen, mechanics, electricians, and laboratory, surgical, X-ray, and dental technicians. Many routinely were sent to specialist schools. The remaining 20 percent were employed by Army Ground Forces, which afforded servicewomen neither additional educational opportunities nor advance training. Lamented one WAC: “I went in as a stenographer clerk and came out as a stenographer clerk.”

Women’s Army Corps members served in all combat theaters—North Africa, the Mediterranean, Europe, the Middle East, the Southwest Pacific, China, India, and Burma. Overseas assignments were highly coveted, even though the vast majority consisted of clerical and communications jobs, which Army brass considered women to be most proficient at. Only the most highly qualified women received overseas assignments. A detachment of 300 WACs served at Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). Originally stationed in London, these WACs accompanied SHAEF to liberated France and eventually to Germany. Some worked in SHAEF’s G-2 (Intelligence) Section. In Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area skilled office workers were scarce, so 70 percent of the 5,500 WACs in the SWPA worked in administrative and office positions.

The Army acknowledged the substantial contributions of the Women’s Army Corps to the war effort. Of the 150,000-plus WAAC/WAC officers and enlisted women who served in World War II, 637 received medals and citations, including Bronze Stars (565), the Legion of Merit (62), and Purple Hearts (16). In 1978 the Women’s Army Corps was absorbed into the regular U.S. Army.

The Women’s Army Corps (WAC) in World War II

|  |

Left: Using a GI’s military unit number written on the envelope, WACs at this U.S. Army base post office in 1944 England sort mail destined for military personnel in the European Theater of Operations. In February 1945 800 WACs in the all-black 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion arrived in England to rationalize and speed up a chronically chaotic mail processing and delivery system in the last six months of the war. Because personnel at the front moved frequently, the 6888th kept an updated information card on each of the 7 million military and civilian people in the ETO. (For more about this remarkable all-black WAC battalion, see the boxed text above.)

![]()

Right: A WAC armorer repairs a 1903 Springfield rifle, Camp Campbell, Kentucky, 1944. An early WAAC slogan, “Release a Man for Combat,” supposedly had sexual overtones, so the slogan was changed to “Replace a Man for Combat.” Anti-WAAC feelings originated with the many enlisted soldiers who, safe and comfortable in their stateside jobs, did not necessarily want to be “freed” for combat abroad. Neither did their mothers, wives, sisters, and fiancées. A negative public image of the female soldier emerged in 1943 and rumors abounded such as this one: 90 percent of the enlisted women are prostitutes and 40 percent are pregnant. Scurrilous rumors were sometimes started by resentful civilian workers who feared their jobs might be taken from them by arriving female servicemembers. Prevailing stereotypes of the woman’s role in American society also tended to limit the initial range of employment for the first wave of women in the Army. The press, however, was usually sympathetic to the adjustments being made by or caused by women in the military and sectors of the economy affected by critical labor shortages.

|  |

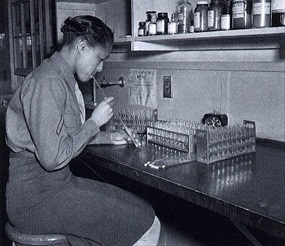

Left: Women recruiting posters sometimes played on the WAAC’s initials, as when Major Charity Adams, the first African American officer in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, famously pointed to a 1943 Army recruitment poster: “Women! Answer America’s Call. Serve in the W.A.A.C.” It may have been enough to induce this young African American, a laboratory technician pictured above, to volunteer for the WAACs. She is shown conducting an experiment in the serology lab at Fort Jackson Station Hospital, South Carolina, in 1944.

![]()

Right: In this photo WACs assigned to the U.S. Eighth Air Force in England operate teletype machines. The first overseas contingent of WACs landed on July 14, 1943, in England in support of the U.S. Army and Army Air Forces. Under the USAAF’s 2 commanding generals, Lt. Gen. Ira Eaker and Lt. Gen. James Doolittle, the Eighth Air Force played a leading role in the Allies’ heavy bombardment operations that reduced German cities, armament factories, communications networks, and oil refineries to useless rubble, thereby hastening the end of the conflict in Europe.

Women’s Army Corps (WAC): “It’s Your War, Too,” U.S. War Department Film, 1944

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click