CHURCHILL’S CALL TO ARMS VS. HITLER

London, England • May 13, 1940

As Adolf Hitler’s armies raced across Europe, seemingly unstoppable, gobbling up country after country for Nazi Germany, and (God forbid) perhaps Britain herself, Winston Churchill succeeded a war-weary Neville Chamberlain as British prime minister on May 10, 1940. Chamberlain had appointed Churchill to be First Lord of the Admiralty, a political position with responsibility for directing and controlling the Royal Navy and Marines, on the same day Britain had declared war on Germany, September 3, 1939. This was the second time Churchill had headed the Admiralty Department—the first had been during the First World War—and the appointment was well-received by Britons, even bumping up the popularity of Chamberlain for several months until the prime minister lost favor nationally and even among some members of his own Conservative Party at the end of the eight-month so-called “Phony War,” when in April 1941 Germany overran tiny Denmark and assaulted Norway. The Anglo-French debacle in stiffening Norwegian resistance to the Nazi invasion prompted Chamberlain to consent to seeing the driven Churchill rewarded with his party’s most important prize, the prime ministership. Churchill, convinced “that I had been walking with destiny, and that all my past life had been preparation for this hour and for this trial,” assembled a new coalition government of Conservatives, Laborites, and Liberals, plus a smattering of ministers with no party affiliation.

Churchill and former Prime Minister Chamberlain entered a packed House of Commons on this date, May 13, 1941, 3 days after news had reached a still-shocked London of Germany’s invasion of the Low Countries and France. After a lukewarm reception from fellow Members of Parliament—Churchill was unpopular in many circles, especially among Chamberlain loyalists still smarting over the change in top leadership—Britain’s new prime minister uttered one of the greatest calls-to-arms ever: “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat,” he told his listeners. The policy of his new government was “to wage war, by sea, land and air, with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us; to wage war against a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed in the dark, lamentable catalog of human crime.” His government’s aim was “victory at all costs. Victory in spite of all terrors. Victory, however long and hard the road may be, for without victory there is no survival.”

Churchill’s inaugural address as prime minister—his powerful call-to-arms—was followed the next month by 2 more eloquent oratorical instances preceding the June 22, 1940, French surrender: the June 4 “We shall fight on the beaches” speech and the June 18 “This was their finest hour” speech 1 day after the proposed Franco-German armistice was announced. In his June 4 speech, Churchill contemplated the impending military defeat of his continental ally France and the real possibility of having to defend the besieged British Isles on English invasion beaches, in English fields and hills, and in streets—all this without undermining his May 13 declaration of “victory, however long and hard the road may be.” In the last of the 3 speeches Churchill recognized the looming battle facing all Britain. “The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned on us. . . . If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be freed. . . . But if we fail, then the world . . . will sink into the abyss of a new dark age. . . . Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves, that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will say, ‘This was their finest hour’.” Churchill’s 3 masterful (and matchless) speeches, like others that followed during the dark years of 1940–1941, inspired and unified his countrymen to soldier on alone, still unbowed, until help came in the form of America’s dramatic entrance into the European conflict on December 11, 1941.

Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill: Divergent War Aims

|  |

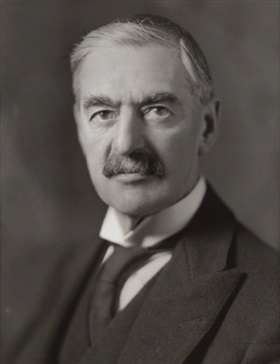

Left: Neville Chamberlain (1869–1940), British prime minister from May 28, 1937, to May 10, 1940. In his last month in office, the May 1940 Gallup poll showed Chamberlain’s unfavorability rating at 67 percent, which stood in stark contrast to his huge popularity as an international “peacemaker” in the wake of the September 1938 Munich Conference. The 4‑power summit of European political leaders in Bavaria’s capital appeased Hitler by rewarding Nazi Germany with Czechoslovakia’s ethnic-German Sudetenland. Churchill turned his back on Chamberlain’s hitherto futile war aim; namely, trying to induce in Hitler a change of heart and mind by teaching Nazi Germany that aggression in Czechoslovakia and Poland (1939) and Denmark and Norway (1940) could not and must not pay dividends of any kind. Britain’s war aim under Churchill was not the collapse of the German economy or a revolt of the German masses and a compromise peace as Chamberlain had hoped for; rather, it was a complete and clear-cut military victory over the predatory nation—a return to total war of the kind that eventually brought down Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany during the First World War. Chamberlain, after stepping down as prime minister in May 1940, remained in Churchill’s coalition cabinet as Lord President of the Council, presiding over meetings of the Privy Council, until October 3, 1940, succumbing to bowel cancer the next month at age 71.

![]()

Right: Prime Minister and Minister of Defense Winston Churchill (1874–1965) flashing his famous “V” for victory sign following his return from Washington, D.C., to No. 10 Downing St., London, June 5, 1943. Named the Greatest Briton of all time in a 1999 BBC poll, Churchill is widely regarded as being among the most influential people in British history, consistently ranking well in opinion polls of 20th-century British prime ministers. Interestingly, Clement Attlee, Churchill’s Labor Party successor in 1945, ranked first in 3 out of 4 recent polls (2004–2016). In the 2004 online poll of 258 academics who specialized in 20th‑century British history and/or politics, Attlee ranked number 1, Churchill 2, and Chamberlain 17 out of 20.

Excerpt from Winston Churchill’s First Speech to the House of Commons: “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat”

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click