CHURCHILL ORDERS DUNKIRK RESCUE

London, England · May 19, 1940

Following Britain and France’s declaration of war on Germany on September 3, 1939, neither of the Allies committed to launching a significant land offensive against Adolf Hitler’s Germany as punishment for the invasion of its eastern neighbor, Poland. The most the British were prepared to do was deploy a 315,000‑man expeditionary force, with aircraft and artillery, to the Franco-Belgian border.

Hitler, however, was busy making preparations to end the so-called Phony War, as this early and quiet phase of World War II came to be called. His war in the West began on May 10, 1940, when Wehrmacht forces invaded the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A series of Allied counterattacks failed to sever the German spearhead through Belgium’s Ardennes Forest, which quickly reached the English Channel, swung north along the French coast, and threatened to capture the Channel ports and trap the Allied troops and their heavy equipment before they could escape to England.

On this date in 1940 British Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered the British Admiralty to engage in a rescue mission that became known as the “Miracle of Dunkirk.” Using a “fleet” that grew to over one thousand vessels, ranging from Royal Navy destroyers and other warships, cross-Channel ferries, pleasure steamers, to craft as small as cabin cruisers manned by civilian crews, Operation Dynamo initially targeted rescuing upwards of 45,000 members of the British Expeditionary Force. However, Operation Dynamo succeeded in bringing some 198,229 men of the BEF along with 139,997 French and some Belgian troops to safety in England. Bad flying weather and Hitler’s dithering saved the nucleus of the British Army and the germ of the Free French Forces (Forces françaises libres), or FFL, from certain destruction. The evacuation ended on June 4.

Seen by Hitler and his inner circle as a British defeat, Dunkirk became a major victory for British wartime morale, the Dunkirk Spirit. Four years later the Western Allies returned to the continent—to Normandy on the French coast, over 200 miles south of Dunkirk. On June 6, 1944—D-Day—the Allies were outfitted with the largest assemblage of invasion ships, aircraft, men, and equipment in history. In less than 24 hours, 176,000 troops had disembarked from 4,000 transport ships to begin the West’s successful assault on Hitler’s “Festung Europa” (Fortress Europe).

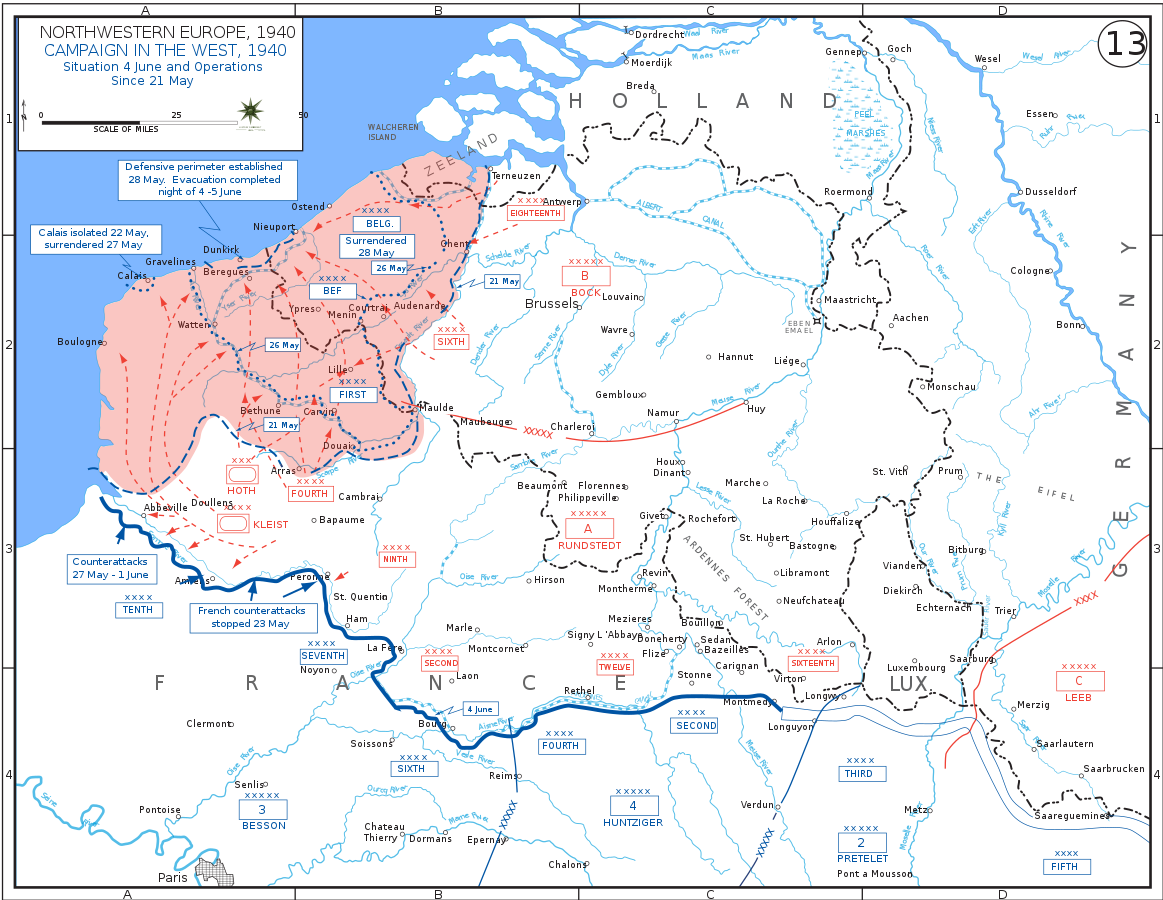

Operation Dynamo and the Rescue of the British and French Armies at Dunkirk, France’s Northernmost Point, May 26 to June 4, 1940

Above: Dunkirk pocket, France, June 4, 1940, the last day of Operation Dynamo.

|  |

Left: A British soldier on a Dunkirk beach fires at strafing German aircraft. During the Battle of France (May 10 to June 22, 1940), the British Expeditionary Force suffered 11,000 killed, 14,070 evacuated wounded, and 41,030 taken prisoner.

![]()

Right: A British fishing boat picks up troops off the coast of Dunkirk while a Stuka’s bomb explodes a few yards away. In nine days, 331,226 British and French soldiers were rescued by around 220 warships and sundry 700 “little ships.” Not only did the rescue operation turn a military disaster into a story of sacrifice and heroism that served to raise and sustain the morale of Britain’s wartime populace, it allowed the British Army to recuperate and rebuild itself for the task of liberating France four years later.

|  |

Left: British troops evacuating Dunkirk’s beaches. Many of the approximately 198,229 men of the BEF who were rescued stood for hours in shoulder-deep water, waiting to board vessels. Despite the success of the rescue operation, all heavy equipment and vehicles had to be left behind: 2,472 guns, almost 65,000 vehicles, and 20,000 motorcycles. More than 75,000 tons of ammunition and 162,000 tons of fuel were also abandoned.

![]()

Right: A wounded French soldier being brought ashore on a stretcher at Dover, England. Of the more than 100,000 French soldiers evacuated from Dunkirk, only about 3,000 chose to join Charles de Gaulle’s Free French army in London. The rest were repatriated back to Brest, Cherbourg, and other French ports in Normandy and Brittany, where roughly half of them were redeployed against the Germans.

|  |

Left: British troops evacuating to ship via a lifeboat bridge. The British Ministry of Shipping telephoned boat builders around the English coast, asking them to collect all boats with shallow draft that could navigate the waters off Dunkirk’s beaches. Nineteen lifeboats of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution sailed to Dunkirk.

![]()

Right: French troops rescued by a British ship at Dunkirk. Between 30,000 and 40,000 French troops were captured in the Dunkirk pocket. For many French soldiers who were repatriated to France, the Dunkirk evacuation was not a salvation, but represented only a few weeks’ hiatus before being made POWs by the German Army following the Franco-German armistice of June 22, 1940.

Contemporary Newsreel of Operation Dynamo, the Allied Evacuation of the Dunkirk Pocket, May 19 to June 4, 1940

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click