CHURCH UPROAR UPENDS NAZI T-4 KILLING PROGRAM

Berlin, Germany • August 24, 1941

On this date in 1941 Adolf Hitler cancelled the Aktion T-4 euthanasia program that he had personally put in place in September 1939. Normally Hitler had a policy of not issuing written instructions for policies relating to what would later be called crimes against humanity, but he made an exception when he provided written authority for the euthanasia program in a confidential October 1939 letter. In the months since its introduction, the euthanasia program, known as T‑4 after the address of its headquarters on Berlin’s Tiergartenstrasse, had provoked opposition from both the German public and influential church leaders, particularly the Bishop of Muenster, Clemens August von Galen.

Von Galen’s August 3, 1941, sermon, the last in a 3‑week series of verbal assaults on the Nazis’ terror tactics and racial and anti-Christian policies, caused shockwaves in Germany: “I am reliably informed,” he told parishioners (as recounted in Wittman and Kinney’s The Devil’s Diary, p. 326), “that in hospitals and homes in the province of Westphalia, lists are being prepared of inmates who are classified as ‘unproductive members of the national community,’ and are to be removed from these establishments and shortly thereafter killed. The first party of patients left the mental hospital at Marienthal, near Muenster, in the course of this week.” State-approved euthanasia, von Galen protested, was nothing short of murder, unlawful by German and divine law (Fifth Commandment). Incensed leading Nazis demanded von Galen’s head. Hitler demurred, planning his revenge for later. Despite secretly suspending Aktion T‑4 21 days after von Galen’s open attack on the euthanasia program, Hitler permitted it to operate unofficially until his own death in April 1945, by which time the murder of psychiatric patients would claim 216,400 victims’ lives.

The principal architect and co-director of the T-4 program was none other than the Fuehrer’s personal physician, Dr. Karl Brandt. T‑4 physicians systematically killed those deemed “unworthy of life” (“lebensunwertes Leben”), including those considered “genetically inferior,” “racially deficient” (“minderwertige Rassen,” meaning Jews, Slavs, and Gypsies), “maladjusted” (usually teenagers), and mentally or physically impaired. Even German civilians who suffered mental breakdowns after air raids were “selected for treatment.” As a result of the T‑4 program, by the end of 1941 between 75,000 and 100,000 children and adults had been killed by lethal injection, starvation, or in gassing installations designed to look like shower stalls (a foretaste of Auschwitz and other death camps). Parents or relatives of those killed were typically informed that the cause of death was pneumonia or a similar ailment, and that the body had been cremated. Other bodies were secretly buried.

Operation Barbarossa, the June 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union 2 months earlier, opened up rich new opportunities for newly displaced T‑4 personnel, and they soon set themselves up in the conquered eastern territories working on a vastly greater killing program: the “final solution of the Jewish question.” In the concentration and death camps in Poland, Brandt oversaw and participated in sadistic “medical experiments” on inmates that continued unabated until the approach of Soviet armies in 1945. At the postwar Nuremberg trials, Brandt was the lead medical defendant. Unrepentant to the end, he was convicted and sentenced to hang, an act carried out on June 2, 1948.

Aktion T-4, the Nazis’ Euthanasia Program, 1939–1945

|  |

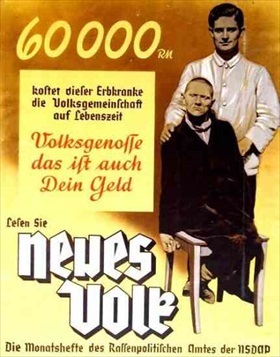

Left: This circa 1938 poster reads in part: “60,000 Reichsmarks is what this person suffering from a hereditary defect costs our community during his lifetime. Fellow citizen, that is your money too.” Another poster compared what an average German worker spent on his family with what taxpayers spent on caring for those in institutions: “Every day a cripple or blind person costs 5 to 6 [Reichmarks], a mentally ill person 4, a criminal 3.50. A worker has 3 to 4 [Reichmarks] a day to spend on his family.” Many of the political initiatives of the Nazis arose from within the scientific and intellectual communities, particularly among eugenicists within the United States as Hitler was fond of pointing out and extolling. (The Rockefeller Foundation and the Carnegie Institute, for example, directed the flow of what is equivalent in today’s currency to millions of dollars to hundreds of German eugenics researchers prior to World War II.) German medical journals openly discussed the need, not only of finding solutions to minimizing costs of housing the institutionalized, but of finding solutions to Germany’s Jewish and gypsy “problems.”

![]()

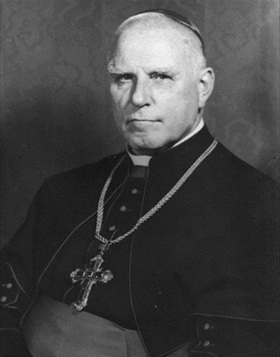

Right: “Lion of Muenster,” Bishop (since 1933) Clemens August Graf von Galen. Politically conservative and a supporter of Nazi nationalism early on, Bishop von Galen came to decry Hitler’s persecution of the Catholic Church. He helped draft Pope Pius XI’s 1937 anti-Nazi encyclical Mit brennender Sorge (in English, With Burning Concern). He attempted to stop the Nazis’ euthanasia program, eventually denouncing it in the most public of all places, from a church pulpit in early August 1941. He also condemned Nazi deportations of Jews to the East. A sermon he gave in 1941 served as the inspiration for the anti-Nazi group “The White Rose,” and the sermon itself was the group’s first pamphlet. Von Galen suffered virtual house arrest from 1941 onward after his sermons critical of the Nazis began circulating throughout Germany, were broadcast on the BBC, and translated and reprinted as flyers, which were air-dropped by the Royal Air Force over Germany and occupied Europe. Although von Galen did not participate in the July 1944 assassination attempt on Hitler’s life, the Nazis linked him to it, finally exacting their retribution. The bishop was whisked away and imprisoned in Sachsenhausen concentration camp some 20 miles/32 km from Berlin until its liberation by the Red Army. He died in March 1946 from an infected appendix diagnosed too late, a few months after he was appointed cardinal by Pope Pius XII. In 2005 von Galen was beatified by Pope Benedict XVI, himself a German.

|  |

Left: The Hartheim Euthanasia Center (German, NS-Toetungsanstalt Hartheim) near Linz in Austria was 1 of 6 euthanasia institutes in the Third Reich. (The others were at Grafeneck, Bernburg, Brandenburg, Sonnenstein, and Hadamar.) Over a period of 16 months between May 1940 and September 1, 1941, 18,269 people were killed at Hartheim. In all it is estimated that a total of 30,000 people were murdered there. Among them were the sick and the handicapped, as well as prisoners from concentration camps too ill to work, such as those from nearby Mauthausen-Gusen. The killings, aided by SS Gruppenfuehrer Reinhard Heydrich’s Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) technical staff, were carried out using carbon monoxide poisoning. RSHA technicians gained expertise in mass killings that would be put to tragic use against Soviet POWs and Jewish civilians over the following years.

![]()

Right: The German town of Hadamar in the state of Hessen housed a psychiatric clinic where 10,072 men, women, and children were asphyxiated with carbon monoxide in a gas chamber designed to look like a shower in the first phase of the T‑4 killing operations there (January to August 1941). Another 4,000 died through starvation and by lethal injection until March 1945. Hadamar citizens were aware of what was taking place at their clinic, especially since the cremation process was faulty. This often resulted in a cloud of stinking smoke hanging over the town. One person recalled: “The stench was so disgusting that when we returned home from work in the fields, we couldn’t hold down a single bite.” (Quoted in Bartoletti, Hitler Youth: Growing Up in Hitler’s Shadow, p. 96.) Local students, who like their parents observed the comings and goings of gray hospital buses loaded with patients on arrival but not departure, would chant, “Here come the murder boxes,” and often taunt each other by saying, “You’ll end up in the Hadamar ovens!” After the war the chief nurse at Hadamar was given an 8‑year prison sentence for her part in the killings at the clinic.

Military Tribunal No. 1, Nuremberg, Germany, November 1946: The United States of America vs. Karl Brandt and Twenty-Three Other Defendants (aka “The Medical Case”)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click