CHINA-BASED B-29S HIT JAPANESE STEEL WORKS

Chengtu, China · June 15, 1944

On this date in 1944 67 B‑29 Superfortresses took off from their base in Chengtu, mainland China, to release 221 tons of bombs on the Imperial Iron and Steel Works at Yawata on the southern-most Japanese home island of Kyūshū. This was the first attack on the Japanese homeland since Col. James Doolittle and his Raiders famously launched themselves off the carrier deck of the USS Hornet more than two years earlier. The June 15 attack inflicted marginal damage on Yawata—only one bomb struck the steelworks. But more than that, the Yawata raid demonstrated to U.S. Army Air Forces Gen. Curtis LeMay, head of the XX Bomber Command in China, that Chinese bases, which had to be supplied with fuel flown over “The Hump” (the Himalayan “Aluminum Trail,” named for the number of planes lost), could not deliver the knockout blows to Honshū, the main island north of Kyūshū, where Tokyo, the nation’s capital, lay. Raids from Chinese airfields against industrial targets continued at relatively low intensity through early January 1945. The first wave of B‑29s attacked Tokyo from their new base in the Marianas in the Central Pacific on November 24, 1944, when 111 B‑29s hit an aircraft factory on the edge of the city. More B‑29 raids continued through the end of the month, when LeMay gave his bomber team a respite. In mid-February Tokyo’s aircraft works were badly hit by carrier-based aircraft. The second of these carrier-based raids was accompanied by nearly 230 B‑29s. At month’s end the B‑29s took over the show. On the night of March 9–10, in a fiery display called Operation Meetinghouse, 334 B‑29s dropped incendiaries that destroyed 267,000 buildings, roughly 25 percent of the city (nearly 16 sq. miles), killed close to 84,000 residents while wounding over 41,000, and cut the city’s industrial capacity in half. The Japanese Imperial Palace was heavily damaged in the firestorm. Emperor Hirohito’s tour of the firebombed city is said to have been the beginning of his personal involvement in the peace process, culminating in Japan’s surrender six months later. Tokyo continued to be bombed through August 15, when the Japanese government announced its acceptance of the Allies’ July 26 Potsdam Declaration and its willingness to capitulate provided the emperor’s sovereignty was maintained.

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”600″ height=”200″ title=”Recommended Reading” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”False” show_border=”False” asin=”1568331495,0312010729,0230613969,1603442375,0141001461,1416584404,1594160392,0811733335,0396087914,0760341222″ /]

The Bombing of Japan, 1944–1945

|  |

Left: B‑29 Superfortresses photographed at Chengtu, China, shortly before they participated in the bombing of Yawata, Japan, on June 15, 1944. Boeing built 3,970 of these four-engine, propeller-driven heavy bombers between 1943 and 1946. B‑29s carried out the atomic bombings that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, respectively. On August 14, 1945, the last day of combat in World War II, B‑29s targeted the Japanese naval arsenal at Hikari on the southern tip of Japan’s main island, Honshū

![]()

Right: Tokyo burns under a B‑29 firebomb assault, May 26, 1945. B‑29 raids on Tokyo began on November 17, 1944, and lasted until August 15, 1945, the day Japan capitulated. Twin-engine bombers and fighter-bombers carried out additional attacks on Tokyo.

|  |

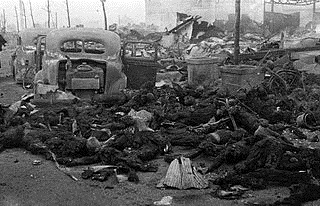

Left: The charred remains of Japanese civilians after the almost unimaginable carnage and destruction wrought by Operation Meetinghouse, the March 9–10, 1945, firebombing of Tokyo. Operation Meetinghouse (“Meetinghouse” being the code name for the Japanese capital) was the deadliest firebombing of World War II.

![]()

Right: A virtually destroyed Tokyo residential section. Over 50 percent of Tokyo, or 97 sq. miles of the city, was reduced to ashes by the end of the war. In all, an estimated 40 percent of Japan’s built-up cities were destroyed in U.S. air attacks in 1944–1945.

March 1945 “Blitz Week” Targets: Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe (Four Consecutive Videos)

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click