BUCHENWALD CONCENTRATION CAMP ESTABLISHED

Mt. Ettersberg near Weimar, Thueringen, Germany • July 15, 1937

On this date in 1937 Adolf Hitler’s Germany established a concentration camp named Buchenwald (“beech forest”), one of the worst manifestations of Nazi sadism and barbarism in all of World War II. Koncentration Lager (KL for short) Buchenwald was located in a heavily wooded area on the northern slopes of the Ettersberg, a hill about 5 miles/7 kilometers northwest of the city of Weimar, the one-time cultural capital of Germany in Thuringia (East-Central Germany), a rabidly pro-Nazi state. Weimar was notable for being the birthplace of German constitutional democracy, the Weimar Republic, around the time Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated in November 1918 and before January 30, 1933, when Hitler became German chancellor and dictator and ended Germany’s short-lived democracy.

Over the years Buchenwald’s 280,000 inmates would be involved in grading camp streets; laying water and sewage lines; and constructing inmate and guard barracks, latrines and washrooms, administrative offices, guard towers, electrified barbed wire fences, storehouses, comfortable homes for officers and administrators, an indoor riding arena, theater, troop casino, dog kennels, a zoo for families of prison service personnel (Schutzstaffel, or SS), an inmate infirmary and library, troop hospital, a crematorium for the mass burning of bodies, shooting ranges, a brothel for service personnel and select inmates, and, most chillingly, a gatehouse with a sinister wing known as the Zellerbau, or “bunker,” a prison containing tiny cells where inmates awaiting execution would be tortured before their deaths.

Men and boys constituted the great majority of Buchenwald’s population. The top camp administrators were two: Karl-Otto Koch (1937–1941), a corrupt sadist who partnered with his vain, cruel, and sadistic wife Ilse Koch, variously nicknamed “Commandeuse of Buchenwald,” “Witch [German, Hexe] of Buchenwald,” and “Bitch of Buchenwald.” (Ilse was incarcerated after the war and died in 1967, a suicide; her husband Karl-Otto was executed by the SS at Buchenwald in 1945.) The other commandant was Hermann Pister (1942–1945). Designed to hold 8,000 prisoners, Buchenwald became the largest of the hundreds of concentration camps within Germany’s 1937 borders. (The largest Nazi concentration/extermination camp was the Auschwitz complex in today’s Poland.) At its intake peak in 1944, Buchenwald admitted 97,867 prisoners and recorded a net loss in the form of 8,644 hospital deaths, to be exceeded by 13,056 hospital deaths in the first 3 months of 1945. (The death tolls do not include prisoners who were executed at the camp or died in transit or on brutal forced marches to Buchenwald or from Buchenwald to other camps.)

The Nazi concentration and death camp system drew little protest from the German public apart from people living downwind of crematoria smokestacks and foul-smelling mass burial sites. The dehumanizing camp routine enabled SS officers, guards, and their assistant Kapos (deputized prisoners, mostly hardened criminals, exercising limited authority over camp inmates) to regard their charges as less than human and thus brutalize them even to the point of death without feeling guilt or compassion. Germans living in the vicinity of camps captured by the Allies claimed ignorance as to what went on in the camps. Allied brass organized mandatory tours for German locals and GIs within 50 miles/80 kilometers of a camp (see photo essay below). Some Germans compelled to traverse the camp from one end to the other registered shock at seeing gas ovens with remains inside, giant outdoor roasting pits with blackened bones, limed cadavers stacked yards/meters high in sheds awaiting mass burial or incineration, and the emaciated skeletons of survivors as if on full display as visitors walked past them. There is one report of a set of Germans snickering after leaving a camp; it did not end well for them. Other visitors truly shuttered at the sights they took in, speechless.

Buchenwald Main Camp and Ohrdruf Subcamp, the Latter Visited by U.S. Generals and Nearby Townspeople

|  |

Left: Buchenwald survivors stare thorough barbed wire fencing, April 24, 1945, after liberation by Third U.S. Army soldiers 13 days earlier. Buchenwald prisoners came from all over Europe and the Soviet Union (successor state Russian Federation)—Jews, Poles and other Slavs, the mentally ill and physically disabled, political prisoners (“enemies” of the Nazi state such as actual or suspected communists, Social Democrats, dissidents, outspoken clergy, and the like), Romani (variously known as Roma, Sinti, and “Gypsies”), Freemasons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and prisoners of war. Ordinary criminals and sexual deviants were also incarcerated there. All prisoners worked as slave laborers, the majority spending 12 backbreaking, deadly hours a day in local armaments factories, rock quarries, or on construction projects. Insufficient and nearly inedible soup made from grass, turnip greens, and decaying vegetables alongside sawdust-laced bread, aggravated by inadequate shelter and squalid living conditions on top of deliberate camp executions, contributed to the 56,545 deaths at Buchenwald and its 139 or 174 subcamps, or satellite camps (number varies between sources), most of them after 1942.

![]()

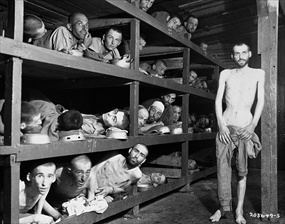

Right: This interior view of a barracks at Buchenwald, April 16, 1945, reveals the stifling confines of the sleeping area. Some of the prisoners used their food bowls as pillows. Disease spread rapidly in such close quarters and accounted for many deaths. In the second tier of bunks, seventh from left, is Eliezer “Elie” Wiesel, Romanian-born American writer, professor, political activist, Nobel laureate, and author of 57 books, including Night, a work based on his experiences as a Jewish prisoner in the Auschwitz and Buchenwald concentration camps.

|  |

Left: Corpses near the gate of Ohrdruf forced labor camp, one of dozens of Buchenwald’s subcamps, still lay unburied, lice crawling over their yellow skin. The smell of death, urine, and feces hung everywhere in the air. Survivors testified that the dead had been shot at close range by SS guards on April 2 because the Germans had run out of trucks for evacuating sick or disabled prisoners as the Americans closed in on the prison camp. Many of the dead had been so emaciated and malnourished that the bullet wounds in their skulls had not even bled.

![]()

Right: Twenty-one U.S. generals and their staffs toured Ohrdruf on April 12, 1945. Some members of the entourage were unable to go through with the ordeal. On April 19, 1945, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower wired both Washington and London to quickly dispatch journalists, members of Congress, and British parliamentarians to Ohrdruf to dispel any allegations that the stories of Nazi brutality were merely propaganda. American newsreels of Ohrdruf called the camp a “murder mill.” (See YouTube video below.)

|  |

Left: Generals Eisenhower, Omar Bradley, George S. Patton Jr., and Manton Eddy, among others, view the charred remains of prisoners who had been doused with pitch and burned on “a mammoth griddle” (Patton’s words) fashioned from crisscrossed railroad track laid over coal and pinewood logs. Long poles with steel hooks on them were used for turning the bodies over. The bodies were still there, some only charred, some half burnt. Below the bodies was a pit in which lay a pile of bones, skulls, and charred torsos. The operation had been done during the evacuation of Ohrdruf by retreating camp officers, guards, and staff. The scene before Patton reminded him of “some giant cannibalistic barbecue.” Remembering their walk through the camp, Bradley remarked how “the smell of death overwhelmed us.” When a camp guard showed Eisenhower how some starved prisoners had torn out the entrails of the dead for food, the general’s face, Bradley wrote, “whitened into a mask.” Bradley was struck dumb, “too revolted to speak.” The camp guard also showed the generals a gallows where men were hanged for attempting to escape. “The hanging was done by a bit of piano wire,” Patton dictated in a memo, “and the man being hanged was not dropped far enough to break his neck but simply strangled.”

![]()

Right: Nude bodies of 40 starved prisoners in a shed at Ohrdruf were layered with lime to mitigate the smell. Patton described the shed as “the most appalling sight imaginable.” When the shed was packed full (about 200 bodies), its contents would be taken to a pit a mile/1.6 kilometers from the camp and buried. Surviving prisoners told Patton that 3,000 of their number had died in the camp since January 1, 1945.

|  |

Left: Soon after visiting Ohrdruf, Gen. Eisenhower ordered every nearby unit not on the front lines to tour Ohrdruf so that the average GI would understand not just what he was fighting for but “he will know who he is fighting against.” To drive the point home and to “brief” GIs on what they might run into in the weeks ahead, photographs from concentration camps like Ohrdruf were distributed to soldiers. On the orders of Eisenhower himself, the mayor of the German town of Gotha, located next to the Ohrdruf complex, toured the camp to see the display of corpses. After seeing the horror, the mayor, professing no knowledge of the affairs of the camp, went home and he and his wife slashed their wrists before hanging themselves. (Without knowing the couple’s motivation, Eisenhower interpreted their suicides as remorse or repugnance for Germany’s past criminal acts and a positive omen for moving Germany forward.) As a rule camp liberators recoiled in disbelief when they heard the perpetual lament of visiting townspeople, who gaped in horror at the piles of decaying bodies and breathed in their putrid stench: “Wir wussten nicht.” (We didn’t know.) “Niemand sagte uns.” (No one told us.) The object of what Germans didn’t know or weren’t told (the missing “it” in sentences like these) was belied most often by the one-way traffic of tens of thousands of locked cattle cars leaving from or passing through German cities, towns, and villages to destinations in the East and the sooty smoke rising from crematoria chimneys everywhere in the Reich. Conceivably some of the townspeople and others like them in this picture who solemnly swore they didn’t know or were never told were the same people who years or months or weeks earlier had jeered, hurled insults, and spat on people taken into Nazi custody—people who tragically ended up dead on a crematorium floor like this in the photo.

![]()

Right: American soldiers forcibly trucked 100 or so Ohrdruf townspeople each day to the “pesthole,” as Patton called the camp, to exhume the bodies in the mass grave and bury them again in individual graves in a public place. A policy Eisenhower mandated required that a stone monument be erected nearby to commemorate the “atrocity victims.” At another reinterment site at Orhdruf’s main camp, Buchenwald, an American officer took no pity on 200 Germans complaining of the stench of decomposed corpses and the day’s heat. “Dig, you sons of bitches,” was all he could bring himself to say. At some locations German civilians were ordered to feed, clothe, and house liberated prisoners at their own expense.

“Liberators and Survivors: The First Moments,” Produced by The International School for Holocaust Studies

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click