BRITISH RETRIEVE GERMAN SECRET WEAPON FROM WRECK

London, England • November 6, 1940

On this date in 1940 a 2-engine German Heinkel He 111 bomber was shot down and sank in the shallows off Southern England. A waterlogged X‑Geraet (“X‑device”) was recovered. The X‑Geraet played a role in the Battle of the Beams, a period early in the war when German bombers were equipped with increasingly accurate systems of radio navigation.

Before the X-Geraet there was the Knickebein (“Crooked Leg”), first tried out in 1939, which broadcast narrow radio guidance beams from occupied Europe. The intersection point of the two beams over enemy targets indicated where bombs should be dropped. (The limited line-of-sight cross-beam development had its inception in electronically assisted safe landings at airports in foul weather or at night.) The way it worked was German bombers would fly into one beam, or set of radio waves, transmitted on one frequency, consisting, say, of a series of Morse code “dots,” and “ride” that beam until the radio operator started hearing the audio tones, consisting of Morse code “dashes,” from the second beam on a second receiver operating on a different frequency. When the radio operator effectively heard a continuous tone (the dashes on one frequency filling in the spaces between the dots on the other), he signaled the bombardier to drop the bomber’s payload.

Knickebein (officially “X-Leitstrahlbake,” or “Direction Beacon”) was used early in the Luftwaffe’s night-bombing campaign and was succeeded by the four-beam X‑Geraet, which was similar in concept, but it operated at much a higher frequency (60 MHz, not 30 MHz) and was used to greater effect. The British city of Coventry, with its 14th‑century Gothic cathedral, was its best-known victim on the night of November 14/15, 1940. The Y‑Geraet was an improvement over the X‑Geraet in that it used a single narrow beam from the ground station pointed over the target. Daytime bombing could rarely achieve the accuracy of these nighttime bombing raids. By way of example, bombs dropped using the X‑Geraet were placed within 100 yards/91 meters of the device’s centering beam, good enough to hit a large factory.

The British scientific community fought back with a variety of its own increasingly effective countermeasures involving jamming (i.e., throwing out powerful radio noise over a wide range of frequencies to disrupt radio transmissions), “bending” or distorting the German navigational beams, and producing false signals that tricked the Germans into dropping bombs far from their intended targets. Three consecutive raids on Britain’s second-largest city, Birmingham, between November 19 and 21/22, 1940, less than a week after the successful Coventry raid, were disrupted by jamming. British electronic wizards were slowly gaining the upper hand. But the Battle of the Beams and the back-to-back aerial duo Battle of Britain and the Blitz on British cities, especially London which was a large and easy target, really only ended when the Luftwaffe moved its bombers to the Eastern Front in May 1941, in preparation for Operation Barbarossa, the attack on the Soviet Union and the harbinger of Nazi Germany’s ruinous end.

Battle of the Beams: Defeating Germany’s Radio Guidance Systems

|  |

Left: Map showing Knickebein radio transmitters whose 2 intersecting beams were broadcast from separate locations, with both beams fixed on a target, in this example Derby in the English Midlands: from Schleswig-Holstein near the Danish border, from Kleve near Essen and the Dutch border, or from Loerrach (southwest of Maulburg) in Baden-Wuerttemberg near the border with France and Switzerland. Following Nazi victories in Norway, the Netherlands, and France in April–June 1940, the Germans installed additional Knickebein transmitters in those countries as well. The Knickebein was the predecessor to the more accurate X- and Y‑Geraet systems, which required new, more sophisticated radio equipment.

![]()

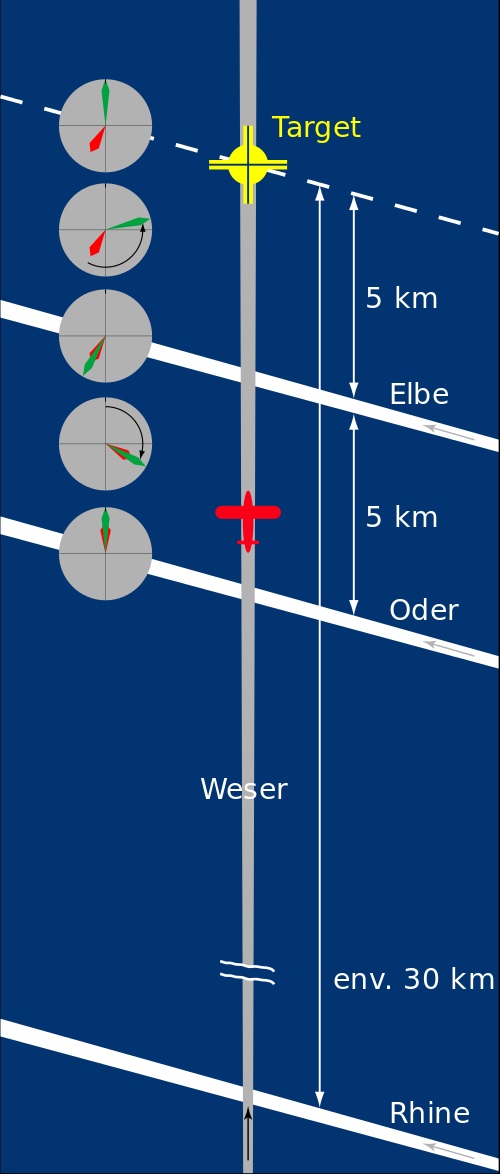

Right: The X-Geraet used a series of beams to locate the target, each beam named after a German river. The guide beam “Weser” was intersected by a series of 3 very narrow single beams, the “Rhine,” “Oder,” and “Elbe.” The intersecting beams accurately measured distances across the guide beam. The “Oder” and “Elbe” were spaced roughly 5 to 10 kilometers/3.1 to 6.2 miles from the bomb release point along the line of “Weser.” The bombs were automatically released on signal from the device. The British were able to defeat the automated system by transmitting a false “Elbe,” so that the bombs dropped prematurely, far short of their target.

Battle of Britain, Part of the “Why We Fight” Series Produced by Frank Capra for the U.S. War Department

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click