BRITISH INTERN SUSPECT GERMANS, ITALIANS

London, England • June 25, 1940

Under the threat of imminent invasion from Nazi Germany, the British government on this date in 1940 began interning all suspect aliens living in the United Kingdom. Thousands of Germans, Austrians, and Italians, including Jewish refugees from the Nazis, were placed behind barbed wire in England (racetracks and unfinished housing projects were typical locations), on the Isle of Man (between Britain and Ireland), or deported to Canada or Australia (7,000 internees)

The botched Allied campaign to assist Norwegians fighting German invaders (April 9 to June 10, 1940) and the rescue of some French citizens during the evacuation of the British Army from the French coast at Dunkirk (May 27 to June 4, 1940) led to an outbreak of spy fever and agitation against enemy aliens. And so all males in Britain aged 16–60 who held enemy citizenship were interned—women only if under actual suspicion. Four days later President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Alien Registration Act (Smith Act), which required noncitizen adult residents living in the U.S. to register and be fingerprinted. Within 4 months of its passage, close to 5 million U.S. aliens had registered, including 40,000 Japanese.

Following on the Smith Act, Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 of February 19, 1942, authorized the Secretary of War and U.S. armed forces commanders to declare parts of the U.S. military areas “from which any or all persons may be excluded.” The order led to the forced relocation, usually to backwater areas of the U.S., of many of the same people, U.S. citizens and aliens alike, who had registered under the Smith Act. More than 117,000 people of Japanese ancestry were affected by FDR’s Executive Order 9066, two-thirds of whom were born in the U.S. These American-born Japanese would spend the next 2 to 5 years wrongfully stripped of their birthright and freedoms and incarcerated without due process of law. Adding to the number of these unfortunates were 11,000 people of German ancestry and 3,000 people of Italian ancestry, along with some Jewish refugees.

Mirroring Roosevelt’s executive order were Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s orders-in-council, the first of which was announced on February 24, 1942. The orders-in-council set in motion the evacuation of all persons of Japanese origin to “protective areas,” mainly in the interior of British Columbia. Some 20,881 Japanese in Canada were uprooted, of whom 13,309 were Canadian citizens by birth. “Evacuees” of Japanese descent in Canada, just like those in the U.S., were held for years without charge.

Of all alien internment, the most brutal was that organized by the Japanese after their armed forces flooded into British, Dutch, and American colonies and territories in the Asia Pacific region following the outbreak of the Pacific War in December 1941. In 1941–1942 approximately 130,000 civilians from Allied countries were interned. The camps—176 camps in Japan, 500 in occupied territories—varied in size; some were segregated by race or gender, but many were mixed gender.

One of the largest unsegregated camps was in the British Crown colony of Hong Kong, which held 2,800 mainly British internees. Unlike prisoners of war, the internees were not compelled to work, but they were held in primitive conditions. Brutality by camp guards was common and internee death rates were high. Japan set up more than 20 internment camps in China and Hong Kong alone, holding some 14,000 people. Now an elite high school, the Shanghai internment camp made famous by J.G. Ballard’s 1984 semi-autobiographical novel Empire of the Sun and Steven Spielberg’s 1987 film of the same name, held more than 1,800 foreigners.

Wartime Internment of Enemy Aliens in Different Parts of the World

|  |

Left: Huyton near Liverpool, England, was the site of 3 wartime camps: an internment camp, a German POW camp opened in 1943 (closed in 1948), and a base for U.S. servicemembers. The internment camp, one of the biggest in Britain, was created to accommodate “enemy aliens” deemed a potential threat to national security. Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s demand to “collar the lot” meant that around 27,000 people in Britain ended up being interned. This picture shows Huyton inmates carrying out bomb disposal.

![]()

Right: When Italy declared war on Great Britain in June 1940, almost 5,000 Italians living in Australia—a member of the British Commonwealth—were herded off to local prisons to be fingerprinted, photographed and numbered, hustled at gunpoint onto trains with barred windows, and sent to Australia’s internment camps or forced to perform forced labor with the Civil Alien Corps from 1943 to 1947. This photograph shows the families of the interned men of the Caminiti clan in the Australian state of Queensland sometime in 1940.

|  |

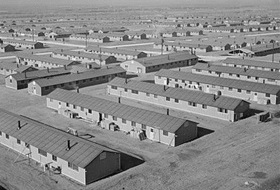

Left: The Granada War Relocation Center (also called Camp Amache) was a Japanese American internment camp located in the hot, treeless, unpopulated southeast corner of Colorado state (truly in the middle of nowhere) roughly 200 miles/322 kilometers east of Denver and 15 miles/24 kilometers west of the Kansas state border. Construction of the camp began in mid-June 1942 with a crew of up to 1,000 hired hands and 50 internee volunteers. The camp opened in August 1942 and had a maximum population of 7,318 persons. With over 560 buildings Amache was the smallest of the ten U.S. relocation centers. Nearly all of those held at the camp were U.S. West Coast “evacuees,” as internees or incarcerees were then known, mostly from the Los Angeles area. Each internee was only allowed to bring one bag or suitcase; therefore, many people were forced to sell what they could or give away their possessions (including pets) before their forced relocation. Amache was surrounded by 4‑strand barbed-wire fencing, with 6 machine-gun watch towers located along the perimeter. Internees were jammed into wooden barracks divided into 20‑by‑25‑ft./6‑by‑7.6‑m “apartments” clustered in 29 residential blocks as partially seen in this photo.

![]()

Right: Lemon Creak Internment camp, June 1944, Slocan Valley, British Columbia. Over 75 percent of Canadian internees were Canadian citizens. Loyalties of Italian and German Canadians were questioned, too. Italian Canadians were considered to be fascist sympathizers and potential terrorists, so they were put under surveillance. Eventually 31,000 Italian Canadians were designated “enemy aliens.” Of these, about 600 were taken from their families and held in prisons and remote camps like the one in this photo.

U.S. Office of War Information Film Justifying the Forcible Removal and Internment of Japanese Residents in the United States

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click