BRITISH DECODE GERMAN BATTLE PLANS

London, England · January 21, 1943

Arguably one of Germany’s greatest assets early in World War II was the Enigma machine. It could encrypt and decrypt sensitive diplomatic and military messages in billions of ways (actually 10 to the 23rd power). The location of U‑boats in the Atlantic, supply convoys, and the orders of battle were sent and received on German Enigma machines.

On this date, January 21, 1943, in Italy’s North African colony of Libya, British commander Bernard Law Montgomery, using Ultra intercepts (the codename for the secret Enigma messages), changed his plans to attack German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps, ordering the drive on the Libyan capital, Tripoli, be directed along the coastal road rather than to the south as planned. Two days later a confident British Eighth Army entered Tripoli. Rommel’s last assault on the Eighth Army—indeed his last offensive in North Africa—initiated on March 6, 1943, was turned back based on Ultra intercepts. Looking for a scapegoat, Rommel attributed his battlefield failures and losses in relief supplies being ferried across the Mediterranean to leaks by senior Italians on his staff.

The Ultra intelligence used by Montgomery was produced on machines that looked like ordinary typewriters but were electromechanical devices that encoded and decoded messages using pre-set alphabetical moving rotors. The continual movement of the rotors (initially 3, then after February 1942 4 rotors used by the German Kriegsmarine) resulted in a different cryptographic substitution after each typewriter key was pressed, scrambling sentences into illogical sequences of letters.

Following pioneering Polish work, British codebreakers in Bletchley Park 50 miles/80 kilometers north-northwest of London deciphered the Enigma code in 1941 (the Poles hadn’t been able to). The Germans believed the Enigma code was unbreakable, but the British team of mathematicians, linguists, and scientists honed in on several design flaws, one being that Enigma could not encrypt any letter as itself. The capture of German codebooks gave the Bletchley team additional help. Though the Bletchley operation was only disclosed in 1974, historians since have generally concluded that the intelligence gained from the Ultra breakthrough shortened the war by 2 or more years. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces, acknowledged in July 1945 that the Bletchley Park workforce “saved thousands of British and American lives and, in no small way, contributed to the speed with which the enemy was routed.”

Bletchley Park and Decoding the Enigma

|  |

Left: Bletchley Park, top-secret headquarters of Britain’s Government Code and Cypher School, where ciphers and codes of several Axis countries were decrypted. This mock-Tudor mansion, with its surrounding buildings (called “huts”), was home to as many as 10,000 men and women during the war, including Britain’s most brilliant mathematical brains, and was the scene of immense advances in computer science and modern computing. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill referred to the Bletchley staff as “the geese that laid the golden eggs and never cackled.”

![]()

Right: Alan Turing (standing) was an English mathematician and wartime codebreaker. At Bletchley Park, Turing (1912–1954) took the lead in a team that designed an electromechanical machine known as a “bombe” (a Polish word for a type of ice-cream dessert) that successfully broke German ciphers. Turing is widely considered to be the father of computer science and artificial intelligence.

|  |

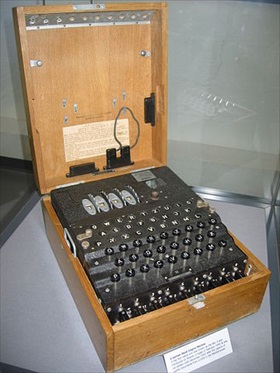

Left: A 4-rotor German naval Enigma on display at Bletchley Park. To encrypt or decrypt a message, an operator typed on the keyboard. Settings on the plugboard (front of machine, partially hidden), in combination with the rotors on the top, determined the code. Billions of combinations were possible. With each key press, the corresponding coded (or decoded) letter lit up the output panel above the keyboard, allowing the operator to copy down the message. The combination of the 2 British-captured cryptographic prizes in May 1941 was crucially important in breaking German U‑boat codes and ultimately in winning the Battle of the Atlantic.

![]()

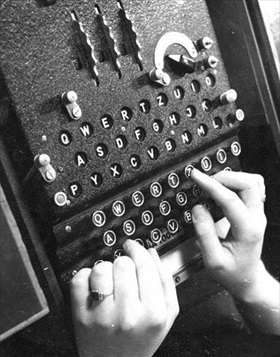

Right: A 3‑rotor Enigma ciphering machine in use by the Luftwaffe, December 1943. An estimated 100,000 Enigma machines were constructed during the war and used principally by the Wehrmacht (German armed services). Almost to the end of the war, Germans had firm faith in the Enigma machine. Indeed, Adm. Karl Doenitz of the Kriegsmarine had been advised that a cryptanalytic attack on his Enigma machines was the least likely of all his security problems. But the truth was that by 1942 Allied codebreakers were deciphering nearly 4,000 German transmissions daily, reaping a wealth of information used by the British and Americans against German naval, air, and land forces.

Scholarly Explanation of Encryption Technology: How Enigma Machine Worked and How the German Code Was Cracked

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click