BRITISH BEST ROMMEL IN BATTLE OF ALAM EL HALFA

Alam el Halfa, Egypt • September 5, 1942

The years-long back-and-forth Western Desert Campaign (June 11, 1940 to February 4, 1943) in the scrubby desert wastelands of Western Egypt and Eastern Libya had reached a stalemate at the end of July 1942, when both Allied and Axis sides licked their wounds in the wake of the quick fall of the British fortress of Tobruk, the best deepwater port in Eastern Libya (June 20–21, 1942; nearly 33,000 Allied soldiers taken prisoner) followed on the heels by the First Battle of El Alamein (July 1–27, 1942, over 13,000 casualties on each side). The British Eighth Army under Gen. Claude Auchinleck had finally fought the aggressive, resourceful German Field Marshal (since June 21) Erwin Rommel’s Panzerarmee Afrika (aka Afrika Korps) to a standstill at the small Egyptian railway station and outpost known as El Alamein. The two belligerent armies were now roughly 60–70 miles/95–112 km from Alexandria, Egypt, headquarters of the powerful British Mediterranean Fleet, which blocked Italian and German reinforcements and supplies from reaching Rommel. To the east of Alexandria lay the Nile Delta and the Suez Canal, which connected the Mediterranean Sea with the Indian Ocean and British India, and beyond Suez the oilfields of the Middle East, possession of which was important strategically to both sides.

Auchinleck knew that his battered soldiers (around 30,000 combat troops) would not be able to push off from El Alamein and take the offensive until September 1942 at the earliest, this after retraining and reorganizing his army. Critical to reorganizing his army was the arrival of infantry replacements, supplies of every description, but especially American armor (300 Sherman M4 medium tanks, one hundred 105 mm M7 self-propelled howitzers, ammunition, spare parts, and 150 instructors). Auchinleck also knew that Rommel’s overextended Panzerarmee Afrika—short 7,000 soldiers who had been captured in First Battle of El Alamein, short also friendly air support, and short transport to deliver replacements, ammunition and fuel to his units—was compelled to renew its relentless drive east before British superiority in men, armor, and matériel made a difference in the outcome. However, before Auchinleck could plan his army’s static defense at El Alamein, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill deposed him and replaced him with Lt. Gen. Bernard Law Montgomery.

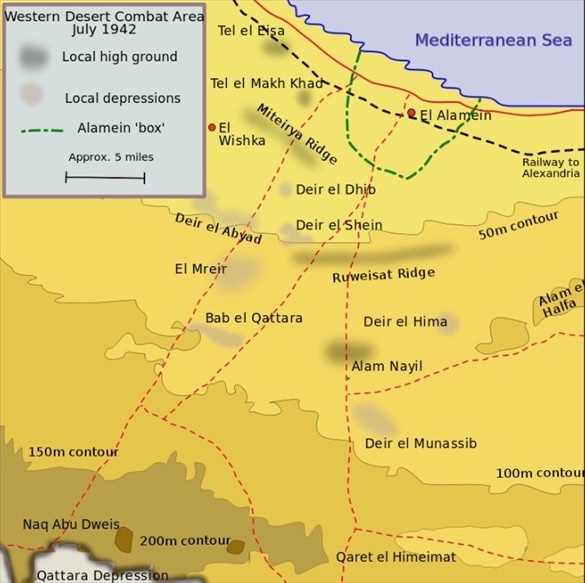

The new commander in chief’s can-do attitude, meticulous planning and preparation, augmented by reinforcements of all kinds, bolstered the strength of the now 150,000-strong Eighth Army. From British Ultra intelligence decrypts, Montgomery was ready for Rommel’s attempt to breach the El Alamein defensive line at Alam el Halfa. Alam el Halfa was a ridge 15 miles/24 km southeast of El Alamein (see right edge of map below). The ridge was vital to the Eighth Army for holding the El Alamein line and to any German drive along the Egyptian coast to Alexandria and the Nile Delta.

Rommel made his move on the night of August 30, 1942. He had 128,000 German and Italian troops and 535 tanks but barely enough fuel and ammunition to make his breakthrough work unless it were quick. The first night he was stymied by British minefields, air assaults, mortars, and the stout resistance of ground troops. Entrenched atop Alam el Halfa, waiting for Rommel’s armor, were a British tank brigade and a division each of artillery and infantry. Two nights later Rommel’s tanks were out of fuel and confronted by every tank in the Eighth Army. British field artillery and air sorties pummeled the static Axis armored units. On the morning of September 2, Rommel called off his offensive. The next day the Axis retreat started. On this date, September 5, 1942, the Battle of Alam el Halfa ended. Victory boosted the morale of Eighth Army soldiers and brass and assured them that the next time they met Rommel’s army, which they did 7 weeks later at the Second Battle of El Alamein (October 23 to November 11, 1942), they’d come out victors again.

El Alamein and Environs, Battleground for British and Axis Forces, July–November 1942

|

Above: Map of the El Alamein and Alam el Halfa battlefields, July–November 1942. The Alam el Halfa Ridge is at the right margin of the map. Rommel sought to swing around the Eighth Army’s left flank during the Battle of Alam el Halfa and make for the coastal highway to Alexandria. Montgomery massed tanks of an armored brigade atop the ridge, stopping cold German probes of the ridge. That night Rommel’s Afrika Korps contingent was out of fuel and confronted by all the tanks of the Eighth Army, which had gathered around the ridge to block the Germans’ way. Throughout the day, the British massed 7 field artillery regiments, which pummeled the static German and Italian armored units within their range. The destruct-a-thon was assisted by 125 sorties flown by the British Desert Air Force. The 6‑day Battle of Alam el Halfa cost the Eighth Army 1,750 men killed, wounded, or captured and 67 tanks plus a modest amount of artillery and antitank guns. Rommel’s Panzerarmee sustained 1,859 German troops killed, wounded, and missing, as well as 49 German tanks, 55 pieces of artillery, and 300 trucks destroyed. The Italians lost 1,051 men, 22 guns, 11 tanks, and 97 other vehicles.

|  |

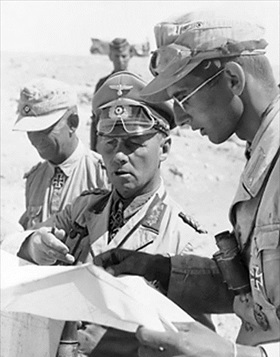

Left: Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, Commander of the German forces in North Africa, with his aides during the Western Desert Campaign, spring 1942. Since June 1941 Axis and British forces had been trading blows across unforgiving reaches of the Libyan desert in a contest to gain control of the Eastern Mediterranean. (For months, beginning in September 1941, the Italians, soon followed by the Germans, had been reading coded American diplomatic communications between the U.S. embassy and Washington, which detailed British troop dispositions and intentions in North Africa.) Rommel, nicknamed “the Desert Fox” (Wuestenfuchs), and his Italian allies seemed to be gaining the upper hand with the British loss of Tobruk fortress and deep-water harbor in June 1942, which put the Germans one step closer to shutting down Britain’s naval base at Alexandria; gaining control of the Suez Canal, the British lifeline to the British-held Indian subcontinent; and securing or destroying the Middle East’s valuable oil fields.

![]()

Right: Lt. Gen. Bernard Law Montgomery watches British Eighth Army tanks maneuvering during the Second Battle of El Alamein, October 23 to November 11, 1942. The British Eighth Army broke the enemy’s lines and British warplanes swept the enemy from the sky. By November 4 Rommel’s army was reeling backwards across the Libyan desert to the safety of Italian-held Tunisia over 1,000 miles/1,600 km to the west. Churchill was thrilled by Montgomery’s sound defeat of Rommel, famously saying, “It may almost be said, ‘Before Alamein we never had a victory. After Alamein we never had a defeat’.” Interestingly, Montgomery’s “British” army, which adopted the nickname “Desert Rats” for themselves, was comprised of men and women from the British Commonwealth (Indian subcontinent, Southern Africa, Australia, and New Zealand), France, Greece, as well as Great Britain.

BBC Presentation: Rommel’s Panzerarmee Afrika vs. Montgomery’s Eighth Army, North Africa 1942

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click