BRITAIN’S SPECIAL AIR SERVICE (SAS) TO BEDEVIL AXIS ENEMY

Cairo, Egypt • July 1, 1941

During World War II Great Britain excelled in creating multiple networks of secret operatives. Perhaps the most famous set of secret agents worked for the Special Operations Executive. Officially formed on July 22, 1940, to “set Europe ablaze,” as Prime Minister Winston Churchill expressed it, the SOE was specifically tasked with conducting espionage, sabotage, and reconnaissance in Axis-occupied—less rarely in neutral—European countries, and to assist local resistance movements in harassing and expelling the enemy occupiers. Among the SOE’s nicknames were “Churchill’s Secret Army” and the “Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare.” An amalgam of several secret departments or sections, the SOE supervised a mixture of covert armed forces personnel and civilians who eventually totaled 13,000 employees of various nationalities.

Less well known was another covert organization, smaller and purely military, the Special Air Service. It was created on this date, July 1, 1941. The SAS was brainchild of 2nd Lt. David A. Sterling of the Scots Guards, stationed in Egypt. Sterling (1915–1990) presented his idea to Gen. Claude Auchinleck, commander in chief of the British Middle East Command, who at the moment was under enormous pressure from Churchill to strike against Axis forces in North Africa with more vigor and imagination. Auchinleck glommed onto Stirling’s unorthodox plan of creating multiple four-member units, each comprising a specialist in weapons, another in explosives, a third in signals and communications, and a fourth in navigation. These tiny teams would do their part in setting ablaze German and Italian supplies lines, airfields, outposts, and ammunition and fuel dumps, among other enemy objectives. Promoted to captain and ordered to recruit a force of 6 other officers and 60 enlisted men, Stirling’s SAS would become one of the most elite and effective special forces in World War II.

By August 1941 Stirling’s little hit-and-run, hide-and-seek commando force was ready for action behind enemy lines, but like the rest of the British Army in North Africa was short on equipment. Their first action—unofficial of course—was a raid on a well-equipped New Zealander’s camp for equipment. Their first official combat foray (Operation Squatter, November 16/17, 1941), a nighttime parachute drop supporting Auchinleck’s Operation Crusader, turned into a fiasco (for one thing, the men lacked parachute training!), so Stirling settled on overland operations as a way of getting his troops back into the business fighting Germans and Italians. Numbering almost 400 men in late 1942, SAS’s freebooting patrols destroyed an estimated 400 Axis airplanes on the ground, severed Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps fuel-and-ammunition railway lines multiple times, blew up numerous supply and bomb dumps, and made almost 50 assaults against key German positions. By the time the Western Desert campaign ended (June 1940 to February 1943), Stirling’s irregulars had been officially designated a British Army regiment, the 1st SAS. In 1943 a second SAS regiment was raised under Stirling’s brother; it served with the Gen. Bernard Law Montgomery’s British First Army in Tunisia.

In March 1944 the SAS Brigade of the British Army Air Corps was formed from 1st through 5th SAS regiments and an F Squadron responsible for brigade signals and communications. Operating behind enemy lines, SAS men found service in North Africa, the Greek Islands, Sicily, Italy, France, Belgium, Netherlands, and Germany. In Operation Houndsworth, one of the most successful and longest (3 months, from June 6 to September 6 1944) clandestine operations, 144 men of 1st SAS were air-dropped into German-occupied France where they blew up the main railway line between Dijon and Normandy 22 times, picked out 30 prime bombing targets for British Royal Air Force fighter pilots, destroyed an enemy oil refinery, and sabotaged a number of smaller targets. 1st SAS sustained 18 casualties versus 350‑plus German casualties. By September Allied armies had forced the Wehrmacht to retreat eastwards toward the German border and Houndsworth was shut down.

Audacious Operators: Men of Britain’s Special Air Service

|  |

Left: Captain David Stirling standing next to 3 Jeep-loads of “The Originals,” as the earliest recruits were known. Bearded, disheveled, and wearing Arab headgear, Stirling’s SAS commandos drove thousands of miles/kilometers across endless North African dunes, wadis, and scrub-dotted wastes. Their transportation ranged from 4‑wheel-drive Chevrolet trucks, Bentley touring cars, to (later on) Jeeps. SAS men typically ladened their Jeeps with Vickers or Browning machine guns, small arms, Lewes bombs (named after its inventor, the devices consisted of diesel oil and plastic explosives), Jerry cans, and water condensers. They subsisted on a makeshift diet of rock-hard Army biscuits, corned beef, chocolate rations, marmalade, tea, dates, tea, snails, onions, turnips, and whatever else they could find in oases and Arab villages. When their water cans ran dry, these irregulars resorted to brackish water from wells.

![]()

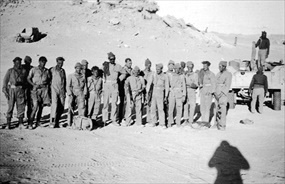

Right: Training at Kabrit (Kibrit) camp 20 miles north of Suez, whence SAS launched Operation Squatter. Among SAS’s ranks were British and Commonwealth soldiers, Free French paratroopers, Greeks, Belgians, and anti-Nazi Germans. A month after their calamitous Squatter mission in mid-November 1941, SAS commandos enjoyed their first success. A handful of Libyan airfields near the Mediterranean coast were targeted. This time the men were transported to their objective by truck. The men sneaked onto the runways and planted time-delayed explosives on the parked aircraft before getting away as fast as possible, suffering not a single casualty by one account or 2 men and 3 Jeeps by another account. Over time Rommel grew impressed with the SAS’s efficiency while Adolf Hitler became more and more incensed—enough to issue his Commando Order of October 18, 1942, which meant that SAS operatives were to be summarily executed if captured. Following Operation Bulbasket, which was meant to hamper German reinforcements heading towards the Normandy beachheads, 34 captured 1st SAS commandos and 7 French resistance fighters (maquisards) were summarily executed by the Germans in July 1944. Three months later in the aftermath of Operation Loyton, again in France, the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) of the Nazi Party’s paramilitary Schutzstaffel (SS) executed 31 captured SAS commandos and dispatched 210 French civilians to concentration camps where 140 died.

|  |

Left: In uniform and wearing their distinctive emblem of flaming sword and “Who Dares Wins” motto on their caps, these SAS commandos pack their Jeep with guns, ammo, and fuel cans for their next operation. No date or place. The SAS was officially disbanded in October 1945 only to be reformed as a Territorial Army regiment, which then led to the formation of the regular army’s 22nd SAS Regiment. Today’s SAS is widely recognized as one of the finest and best-trained special forces unit in the world; it specializes in counterterrorism, hostage rescue, direct action, and covert reconnaissance. SAS personnel reportedly have worked with local fighters around the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv, playing a pivotal role in equipping and training forces with next generation light antitank weapons (NLAWs) to repel Russia’s invasion of its western neighbor. Together with the Special Reconnaissance Regiment and the Special Boat Service, the SAS forms the United Kingdom Special Forces.

![]()

Right: On January 15, 1944, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel assumed operational command of Army Group B, comprising Seventh and Fifteenth Armies stationed in Northwestern France. In this photo likely taken on April 18, 1944, Rommel and his senior officers inspect Atlantic Wall defenses around Calais. The Pas de Calais was where the German High Command expected the Western Allies were most likely to land should they invade the continent because of its short supply line and air routes to England and its relatively direct distance straight into Germany. A month and a half after the Allies had indeed breached the Atlantic Wall on June 6, 1944 (D-Day), in Normandy, not Calais, 6 SAS derring-do parachuted into France on July 25, 1944, with a single mission: capture or preferably kill Rommel at his French headquarters, a secluded chateau above the sloping northern bank of the Seine in the village of La Roche-Guyon, population 540. Unbeknown to the SAS men, Rommel had been seriously injured when his staff car was strafed by a fighter plane and crashed southeast of Caen in Normandy over a week earlier, on July 17. Thus, Rommel was beyond reach convalescing in a hospital. Rather than simply return to base, the commandos elected to ambush trains and attack German troops on route to meeting up with U.S. forces. They ultimately reached safety behind friendly lines on August 12. As for Rommel, instead of becoming a victim of the SAS, he became a victim of Hitler, who demanded Rommel’s suicide owing to his suspected connection with the July 20th attempt on the German leader’s life.

Story of Britain’s Special Air Service (SAS): The Originals

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click