BRITAIN ASKS U.S. FOR DOZENS OF DESTROYERS

London, England • May 15, 1940

On this date, just five days after assuming the top leadership position in Great Britain, Prime Minister Winston Churchill sent a telegram to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt. It was also 5 days since the German Wehrmacht (armed forces) had flooded over the borders of the Low Countries and France, Britain’s wartime ally since September 1, 1939, the date Adolf Hitler chose to begin the destruction of his eastern neighbor, Poland. The fortunes of the 4 democracies in the West rapidly imploded: the Dutch army surrendered on May 15, Belgium’s on May 28, and the French signed an armistice with their traditional enemy on June 22, 1940, after German troops had entered their capital 8 days earlier.

In his telegram Churchill asked Roosevelt, who on May 11, 1940, had declared America neutral in the suddenly enlarged European conflict, for a “gift” of “forty or fifty of your older destroyers” to augment the 60-some destroyers then serving in the Royal Navy. (Britain had entered the war with 200 destroyers, down from the 433 she had at the end of World War I. Some were now sitting at the bottom of the ocean and some were so badly damaged that their future as fighting ships was questionable.) America had plenty of overaged, mothballed World War I‑type “four-pipers” (aka “four-stackers” for the 4 smokestacks common to American destroyers at the time). Of the 170 American destroyers that had been in dry dock or otherwise idle in September 1939, 68 had been returned to active duty. That left 102 theoretically available as fighting ships. Perhaps as many as half that number could see convoy duty with the Royal Navy, protecting the fragile trans-Atlantic lifeline between North America and the British Isles. At the end of July 1940 a desperate Churchill, having lost 4 destroyers and incurring damage to 7 others within the last 10 days, implored the president: “Ensure that 50 or 60 of your oldest destroyers are sent to me at once.”

Roosevelt was in a quandary given the hugely isolationist sentiment in the country and the U.S. Congress. The month before, Congress had enacted a naval appropriations bill, forbidding the sale of “surplus military material” unless the chief of naval operations certified that the sale did not threaten the nation’s defense. To sidestep Congress, the Roosevelt administration hastily drafted a legal rationale to aid Britain that involved transferring 50 antiquated U.S. destroyers to Great Britain in return for 99‑year rent‑free leases to establish naval and air bases in British possessions (Newfoundland and the British West Indies) that were vital to transoceanic trade, aviation, and the Battle of the Atlantic (1939–1945). On September 2, 1940, Roosevelt informed Congress of the Destroyers for Bases Agreement, which raised a huge hullabaloo from antiwar political elements.

Although 50 old warships scarcely made a difference in Britain’s conduct of war in the Atlantic, the executive agreement itself led to further measures to aid countries battling Germany and her Axis allies. Of special note was Lend-Lease, a program that Roosevelt floated in a fireside chat to the nation in late December 1940. Shrewdly titled “An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States,” it became law on March 11, 1941. Initial recipients of food, oil, warships, warplanes, and similar material were the British, the Nationalist Chinese, and the Free French. The program was later expanded to include the Soviet Union and other Allied nations. In return the U.S. was given leases on army and naval bases in Allied countries. Supplies worth $50.1 billion in 1945 (equivalent to over $892 billion today adjusted for inflation) were transferred to America’s allies, representing 17 percent of all U.S. war expenditures between 1941 and 1945.

Roosevelt’s Defense Initiative: Destroyers for Bases in Western Hemisphere

|  |

Left: U.S. destroyers involved in the exchange were built between 1917 and 1922. The U.S. and British navies had begun preparations for their transfer in mid-August 1940. The vintage ships were rehabilitated, provisioned, and sent to Halifax, capital and port city in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, where British crews boarded them and lifted anchor for England. Exemplifying the speed of the handover, the first six warships left for England on September 6, 1940, just days after President Roosevelt had announced the trade, and 40 of the 50 vessels arrived in England before the end of the year. There the ships were refitted to rectify defects, standardized with British equipment, and fitted with Royal Navy antisubmarine detection and weapons systems. This process took several months; thus the majority of what became known as Town-class ships did not become operational until early 1941.

![]()

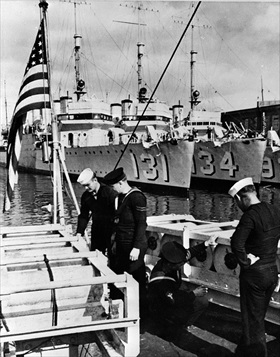

Right: Royal Navy and U.S. Navy sailors inspect depth charges aboard U.S. Wickes-class destroyers. In the background are the USS Buchanan (DD‑131) (recommissioned as the HMS Campbeltown; see below) and the USS Crowninshield (DD‑134) (recommissioned as the HMS Chelsea). On September 9, 1940, both warships were transferred to the Royal Navy. Between 1941 and 1943 Town-class ships, despite their age, participated in the sinking of 10 German U‑boats and 1 Italian submarine while on patrol or as convoy escorts. Some of these well-used Towns saw service in the navies of 4 different nations, among them Canada and the Soviet Union. They also provided escort during the Allied invasion of North Africa, Operation Torch.

|

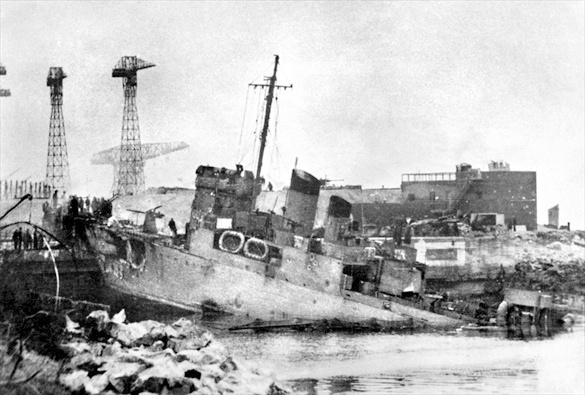

Above: Minutes after midnight on May 28, 1942, HMS Campbeltown, an obsolete U.S.-built Lend-Lease destroyer (DD‑131 in photo above), modified to resemble a 1 smokestack German torpedo boat, steamed boldly up the estuary of the Loire River in German-occupied France heading toward the large Normandie dry dock near the town of St. Nazaire. She was on a suicide mission. Beneath false bulkheads the amphibious party of British commandos and specialized naval personnel had hidden 3 tons of high explosives. The objective of Operation Chariot (aka St. Nazaire Raid) was to neutralize the only French docking facility capable of servicing German warships the size of the 823‑foot/251‑meter, 42,900‑ton Tirpitz, sister ship to the naval battle-damaged Bismarck, which was en route to St. Nazaire for repairs when its captain scuttled the battleship the day before. Neutralize the Normandie dry dock the “charioteers” did by wedging the 33‑foot/10‑meter Campbeltown into the dock’s south gate. When the delayed-action explosion detonated later in the morning it destroyed the faux torpedo boat, completely wrecked the dock’s gate, severely damaged surrounding facilities, and in the process killed nearly 360 enemy soldiers swarming over the boat. The German occupiers never repaired the Normandie Dock and the facility stayed shut until 1948.

Destroyers for Bases Agreement of September 2, 1940

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click