BISMARCK’S BREAKOUT WORRIES ROYAL NAVY

London, England • May 21, 1941

On this date in 1941 the German heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen and the German battleship Bismarck set out from occupied Norway into the main Atlantic shipping lanes, there to act as long-distance commerce raiders. It was the maiden combat voyage of Nazi Germany’s monstrous battleship, the most lethal weapon in any navy’s arsenal, and had been the focus of the Royal Navy’s attention since the battleship was commissioned nearly 2 years earlier.

Germany’s major surface warships, combined with its fleets of submarines and armed merchant raiders, had caused extensive damage and disruption to Britain’s vital transoceanic routes to and from North America almost since the outbreak of European hostilities in September 1939. As well as sinking merchant ships belonging to belligerent and neutral nations alike, the German Navy forced British-bound convoys carrying food and war materials to be diverted or halted, thereby imperiling the very survival of the island nation (click Battle of the Atlantic).

The Royal Navy, continuously seeking out and destroying convoy-prowling German U‑boats, now set out to destroy the 50,000‑ton pride of the Kriegsmarine in the most famous sea chase in history. (U.S. long-range naval patrol aircraft from Iceland and the Bermudas were also active in the search for the German battleship.) On May 27, 1941, off the southwest coast of Ireland, the HMS King George V and the HMS Rodney pulverized the Bismarck with their 14- and 16‑inch/355.6 and 406 millimeter guns, respectively, finishing off the job the Prince of Wales and carrier aircraft from the Ark Royal had begun hours earlier. More than 2,100 officers and enlisted men (including the entire German fleet staff) perished; only 114 survived the sinking.

Much further south, this off the coast of Brazil and also on this date, German U‑boat U‑69 torpedoed and sank the unarmed American freighter SS Robin Moor. Though passengers and crew were permitted to disembark, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared an unlimited state of national emergency a week later in response to the U.S. quasi-war with German U‑boats. (The U.S. still formally considered itself a neutral party in the European conflict.) Roosevelt vowed that America’s so-called “Neutrality Patrol” operating up and down the U.S. east coast, begun on September 6, 1939, with the aim of discouraging German warships from threatening shipping inside U.S. and Canadian waters, would be extended deeper into the Atlantic. On July 1, 1941, Adm. Ernest J. King, Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, established escort services for merchant ships flying flags of any nation sailing between U.S. and Canadian waters and the North Atlantic island nation of Iceland provided that 1 ship in the convoy was American or Icelandic. King instructed U.S. escort vessels to attack any “hostile forces which threaten such shipping” in what Roosevelt declared was “our defensive waters.” The escorting job was made easier when Iceland permitted U.S. forces to be stationed on the island 7 days later.

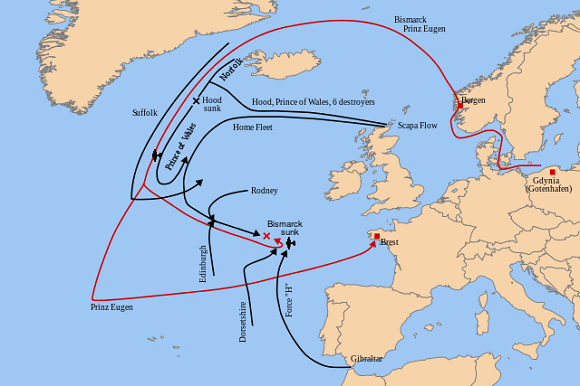

Sink the Bismarck: The Royal Navy’s Operations Between May 21 and May 27, 1941, that Destroyed the Pride of the Kriegsmarine

|

Above: Map of the Royal Navy’s operations against the mammoth German battleship Bismarck and the German heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, with approximate movements of ship groups (red German, black British), places of aerial attacks on the 2 German warships, and the Bismarck’s final resting place. The wrecked battleship was discovered about 400 miles/644 kilometers west of Brest, France, on June 8, 1989, by Robert Ballard, the oceanographer responsible for finding the RMS Titanic.

|  |

Left: The 823-ft./241-meter-long Bismarck on the River Elbe in Blankenese near the North German city of Hamburg. Protected by 13 inches/33 centimeters of armor and armed with 8 massive 15‑inch/381‑millimeter cannons in 4 turrets and a dozen 5.9‑inch/150‑millimeter rifles in 6 turrets, the world’s newest, most-advanced battleship was nevertheless sunk 9 days into her maiden voyage. The voyage began auspiciously enough with the Bismarck quickly and neatly destroying the 20‑year-old, heavily armed but thinly armored British battlecruiser HMS Hood, with a loss of 1,415 officers and seaman (the single-worst disaster inflicted on the Royal Navy in its 4 centuries of existence), and severely damaging the newly commissioned battleship, HMS Prince of Wales, in the ship-to-ship Battle of the Denmark Strait, May 24, 1941. (The Denmark Strait is a wide channel separating Greenland from Iceland; see map above.) In all, 6 British battleships and battlecruisers, 2 aircraft carriers, 13 cruisers, and 21 destroyers—in other words, all available warships—were committed to the search-and-destroy chase. Thrown into the mix were dozens of patrol aircraft, making this the largest force ever tasked with the destruction of a single ship.

![]()

Right: British aircraft carrier Ark Royal with a flight of Fairey Swordfish canvas-covered biplane torpedo bombers overhead, circa 1939. One of these obsolete planes scored a hit that rendered the Bismarck’s steering gear inoperable, making the battleship’s destruction the next morning all but inevitable. At least in the North Atlantic, Germany’s floating gun platforms like the Bismarck and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen would no longer decide naval engagements in their favor.

|  |

Left: Surrounded by shell splashes, the Bismarck burns on the horizon, bringing to an end a chase that had lasted 5 days and covered more than 1,700 nautical miles/3,148 kilometers. Four British warships fired more than 2,800 shells at the Bismarck, scoring more than 400 hits, which reduced the battleship to a shambles, and avenging the Hood. The photo was taken on May 27, 1941, from one of the Royal Navy warships chasing her. German demolition (scuttling) charges were the direct cause of the Bismarck’s sinking, the stern sliding under the surface first as the ship capsized to port.

![]()

Right: Two British warships attempted to rescue the Bismarck’s survivors after the HMS Dorsetshire (shown here) managed to inflict a coup de grâce by firing 2 torpedoes into the badly listing battleship. A U‑boat alarm, however, caused the ships to leave the scene after having rescued only 110 out of some 400 sailors in the water. Later a German U‑boat and a German trawler picked up 5 survivors.

Combat Footage of British Air and Naval Forces Sinking the German Battleship Bismarck, May 27, 1941

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click