BILL MAULDIN, SOLDIER CARTOONIST, STORMS SICILY BEACH

Near Scoglitti, Sicily, Italy • July 10, 1943

On this date 21-year-old Oklahoma national guardsman Bill Mauldin landed on the southwest coast of Sicily with K Company, 180th Infantry Regiment, 45th Division as part of Operation Husky (July 9/10 to August 17, 1943). Mauldin is less known for his 3‑year service in World War II than for his cartoon drawings of American enlisted men—chiefly riflemen like himself—through his main characters, Willie and Joe, who appeared in newspapers between 1940 and 1945. Though Mauldin mostly saw combat in Italy, where he created the majority of his cartoons, his grizzled, mud-covered, combat-weary “dogfaces” or “doggies”—as he called combat enlistees—achieved star-status owing to their appearance first in the weekly 45th Division News in 1940 Oklahoma (soon syndicated in dozens of national newspapers), then in early spring 1944 in the daily Stars and Stripes. The widely popular 8‑page Stars and Stripes was read by hundreds of thousands of servicemembers in all European and African theaters of operation and, after May 1945, in the Pacific theater. Mauldin was assigned to work full-time at the Stars and Stripes. He wrote about and drew humorous caricatures of riflemen, medics, combat engineers, artillery observers, and other frontline soldiers from close to 20 divisions whom he met, lived, slept, and served with. He faithfully shared their spoken words and thoughts in his single-panel cartoons (see examples below).

Though linked together at the hip in the public’s mind, sharp-nosed Willie and pug-nosed Joe (Mauldin himself) first appeared separately in the cartoonist’s drawings—Joe before Pearl Harbor and general mobilization, Willie afterward. Representing average American GIs, the 2 cartoon soldiers became best buddies over the next several years, bellyaching about their war-weariness, homesickness, boredom, monotony, rain, snow, freezing cold weather, cursed mud and wet foxholes, K‑rations, smelly feet, and the thought that one or both of them might not make it out of the war alive. Ernie Pyle, a Pulitzer Prize-winning American journalist and widely read war correspondent, admired Mauldin for his “terribly grim and real” drawings and for his droll captions that captured Joe and Willie’s habitual dogface appearance (unkempt faces, their worn-out boots, wet smelly socks and feet, baggy, mud-caked uniforms) along with some of their feelings—in other words, what it was to look like and be a foot soldier trapped in a miserable war for months on months or years. Mauldin’s targeted audience roared with laughter as service men and women shared the cartoon soldiers’ pain.

Army brass, however, could and did find Mauldin annoying. Chief among the young artist’s detractors was the spit-and-polish-obsessed Third U.S. Army Gen. George S. Patton Jr. He cursed at the 2 cartoon figures over their scruffy, “unsoldierly” appearance. In one of Mauldin’s cartoon panels, Willie and Joe are depicted driving a beat-up jeep. A road sign informed the 2 soldiers “You Are Entering the Third Army [area].” Underneath was a list of fines for GIs entering the area unshaven ($10), without helmet or tie ($25 each), and so on. The caption had Willie telling Joe: “Radio th’ ol’ man [i.e., company HQ] we’ll be late on account of a thousand-mile detour.” Patton’s revenge was a 45‑minute private dressing down of Sergeant Mauldin short of an official reprimand.

Unlike popular war correspondent Pyle who was killed by a sniper on the Japanese island of Iejima (Ie Shima) on April 18, 1945, Mauldin (1921–2003) survived the war with nothing more than a shrapnel wound and a Purple Heart. The first civilian compilation of his work, Up Front, a collection of his cartoons and foxhole-level view of the war in Europe, topped the New York Times best-seller list in 1945 and 1946. Before that Willie, Joe, and Mauldin had a piece in Time magazine with Willie on its June 18, 1945, cover. Mauldin’s postwar attempt to showcase the veteran riflemen back home as civilians was unsuccessful.

Bill Mauldin: Foremost World War II Cartoonist

|  |

Left: This photograph shows Stars and Stripes cartoonist Bill Mauldin, in a fur-lined mountain cap, seated at his desk in an office of the Italian newspaper Il Messagero (The Messenger) in Rome, Italy, ca. 1945. The Stars and Stripes, like its World War I predecessor of the same name, was intended to provide uncensored news from soldiers for soldiers. It was not an organ for the high brass to use. Mauldin had a regular 2‑column space in the Stars and Stripes, giving his simple black-and-white brush-work cartoons a prominent presence in the newspaper. Speaking of the founder of the World War II version of the Stars and Stripes, a former private, now colonel, Mauldin wrote: “Because our paper was exclusively for combat soldiers, we didn’t have to worry about hurting the feelings of high brass hats. . . The great majority of generals and authorities who see the sheet over here leave us strictly alone.” Which wasn’t exactly true. Mauldin confessed that “a few cartoons I had done about generals had a definitely insubordinate air about them.” Mauldin, in a dustup with a deputy theater commander in Italy, was accused of “undermining somebody’s morale” in “the rear echelon.” A corps commander (a general) told the cartoonist to buck up: “When you start drawing pictures that don’t get a few complaints, then you’d better quit, because you won’t be doing anybody any good.” Mauldin later stood his ground when Gen. Patton tried to clean his clock (see above). Maudlin, Up Front, pp. 26–29.![]()

Right: Caption, Willie: “Joe, yestiddy ya saved my life an’ I swore I’d pay ya back. Here’s my last pair of dry socks.” Long-suffering infantrymen were forced to endure rain, mud, more rain, more mud, and so on. “The worst thing about mud,” Mauldin wrote, “outside of the fact that it keeps armies from advancing, is that it causes trench foot. There was a lot of it that first winter in Italy [1943–1944]. The doggies found it difficult to keep their feet dry, and they had to stay in wet foxholes for days and weeks at a time. If they couldn’t stand the pain they crawled out of their holes and stumbled and crawled (they couldn’t walk) down the mountains until they reached the aid station. Their shoes were cut off, and their feet swelled like balloons. Sometimes the feet had to be amputated. But most often the men had to make their agonized way back up the mountain and crawl into their holes again because there were no replacements and the line had to be held.” Mauldin, Up Front, pp. 35–37.

|  |

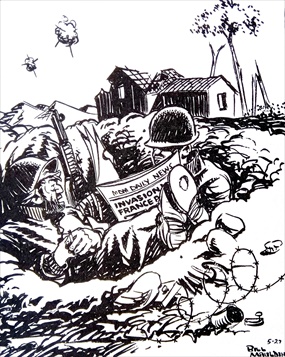

Left: As Mauldin put it, for a rifleman occupying a cramped foxhole, snug as a bug in a rug (if such a thing were even possible), nothing is more precious or vital than that nothing disturbs that axis. Willie weighs which axis of war is important to him and which isn’t. “Th’ hell this ain’t th’ most important hole in the world,” Willie yells to Joe over the sound of exploding artillery. “I’m in it.” If all hell hasn’t broken out to disturb the spinning axis, the war may be considered going well no matter what is happening off in the distance. But if Willie and Joe are sweating out a fierce artillery barrage and Joe next to him happens to be severely injured, even killed by a piece of flying shrapnel, then the war has gone horribly wrong. Mauldin, Up Front, pp. 19–20.

![]()

Right: Caption: Joe: “I can’t git no lower, Willie. Me buttons is in th’ way.” In Stephen E. Ambrose’s introduction to Mauldin’s book Up Front, the famous author and historian wrote (pp. viii–ix): “For the infantrymen, just about the worst experience was being caught in the open in a shelling. They would press themselves to the earth and pray to God. . . At other times, they thought ‘this must be the end of the world.’ One veteran told me that he knew I wouldn’t believe it but that I couldn’t imagine how small a human being can make his body. ‘During a shelling,’ he said, I could get my whole body under my helmet.’ Mauldin’s cartoon speaks to this point.” Mauldin, Up Front, p. 39.

|  |

Left: Caption: Willie to Joe, “I feel like a fugitive from th’ law of averages.” Mauldin remarked: “All the old divisions are tired—the outfits which fought in Africa and Sicily and Italy and God knows how many places in the Pacific. . . [M]en in the older divisions . . . have seen actual war at first hand, seeing their buddies killed day after day, trying to tell themselves that they are different—they won’t get it; but knowing deep inside them that they can get it.” Mauldin, Up Front, pp. 38–39.

![]()

Right: Caption: “Fresh, spirited American troops, flushed with victory, are bringing in thousands of hungry, battle-weary prisoners . . .” Mauldin chided the States-side press for sometimes being two-faced. “I drew the German soldier as a poor unfortunate who didn’t want to be there,” he penned in Up Front, which is just the way he had drawn Willie and Joe. In 1944 Mauldin won the first of two Pulitzer Prizes in Editorial Cartooning for his depiction of grimed-faced German POWs being herded by equally grimed-face GIs trudging to a holding pen in the rear. Mauldin noted for the record, “After a few days of battle, the victorious Yank who has been sweeping ahead [in battle] doesn’t look any prettier than the sullen superman he captures.” Mauldin, Up Front, pp. 21–22.

Medley of Bill Mauldin’s Willie and Joe Cartoons Set to 1940s Music

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click