BATTLE OF MANILA ENDS IN GRIM VICTORY

Manila, Philippines • March 3, 1945

On this date the monthlong Battle of Manila ended when U.S. and Filipino forces captured Manila’s Finance Building. It was the last set of government offices in the Philippine capital still occupied by a scrum of Japanese sailors and soldiers serving under the fanatical ex-Rear Adm. Sanji Iwabuchi, a suicide the week before. Iwabuchi was nominally part of Japanese Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita’s Fourteenth Area Army, which had been tasked with defending the Philippine archipelago from the predicted American invasion. Iwabuchi, however, had received the blessings of the naval staff in Tokyo to defend the capital with his 12,500-strong 31st Naval Special Base Force augmented by 3,750 remaining army security troops. Army general Yamashita never once contemplated sitting tight in Manila for fear of his and his men being trapped in nasty urban warfare in a city with close to a million residents. Instead, without declaring Manila an “open city,” meaning a belligerent may enter the city unopposed by his opposite number, Yamashita simply vacated the Philippine capital and settled on forward-deploying his 262,000 defenders north and east of Manila to engage the enemy head-on. The general’s departure gave Iwabuchi all he needed to move into the vacuum despite Iwabuchi’s receipt of Yamashita’s direct order to withdraw from Manila without combat.

The liberation of the Philippines from Imperial Japan commenced with Sixth U.S. Army amphibious landings supported by naval and air units on the Eastern Philippine island of Leyte on October 20, 1944. (That was 10 days after Yamashita had assumed command of the Fourteenth Area Army.) Similar landings on populous Luzon Island at Lingayen Gulf on January 9, 1945, and a second one on January 15 roughly 45 miles/72 kilometers southwest of Manila formed a vice to squeeze Manila’s Japanese defenders. The Americans were welcomed and assisted by members of the underground Philippine Commonwealth Army and the Philippine Constabulary and hundreds of guerrillas. On the evening of February 3 the Americans and the Filipinos had advanced into the capital. The Battle of Manila (aka the Manila Massacre) turned truly grisly as Iwabuchi’s troopers fought with a determination, ferocity, and bestiality rarely matched elsewhere in the war between the U.S. and Japan.

Murder and mayhem committed by Iwabuchi’s thugs began the moment U.S. Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s forces charged into Manila. The renegade admiral presided over the slaughter of tens of thousands of Manilenos—men, women, and children—in some of the most cruel and horrible ways imaginable. In an early engagement, U.S. infantrymen drove toward Manila’s Pasig River and Bilibid Prison where 1,275 internees were freed. As they did, Iwabuchi’s men dragged scores of Filipino civilians to the Pasig’s estuaries, where they bound them, bayoneted them, shot them, and slashed their throats and bellies. More than 100 civilians were either left to rot or had their bodies burned. In a later engagement in Manila’s oldest district of Intramuros, Iwabuchi’s butchers separated neutral Spanish citizens—mostly priests—from 3,000 Filipinos and gunned down the latter while imprisoning the former without food or water. Sensing they would all die anyway, Japanese troops burned down buildings, raped women and girls, and slaughtered umpteen thousands of Filipinos in a lethal replay of the Rape of Nanking (China, mid-December 1937 to early February 1938).

Manila was the first large city the U.S. Army retook in the Pacific War. A thousand American soldiers lost their lives and over 5,500 were wounded. Killed too were more than 16,600 Japanese occupiers. Worse yet was the massive number of Manila’s residents—100,000, or one‑tenth of the city’s population—who perished. Most were killed by a fanatical enemy who made a fetish of murdering Filipinos. Other Manilenos, unfortunate casualties of war, died in their homes or shelters as the Americans ferreted out the enemy. The Allied victory was devastating.

Scenes of Manila’s Liberation, February and March 1945

|  |

Left: Aerial view of the destruction of Manila’s Intramuros (“Walled City”) in May 1945. Intramuros was the oldest district, the historic core of the city of Manila built during the Spanish Colonial Period. The quarter‑square-mile/0.65‑sq.‑km mini-city was heavily damaged during the battle to retake Manila from the enemy, which ended almost 3 years of Japanese military occupation of the Philippine capital.

![]()

Right: American troops move into devastated Intramuros, February 23, 1945. As GIs forced their way through rubble they had created during the preceding 7 days of constant bombardment, Manilenos reportedly were happy to see them. They sang “God Bless America” and kids shouted “Victory Joe!” while soldiers handed out candy and Hershey bars. After Poland’s Warsaw, Manila, renowned as the “Pearl of the Orient,” was the most heavily damaged of all Allied capitals during the war.

|  |

Left: Taking partial cover behind a stone wall, U.S. soldiers fire at Japanese troops ensconced within the confines of the historic Spanish fortress of Intramuros with its massive walls (40 ft/12 m thick at the base and 20 ft/6 m at the top) and giant dungeons. The centuries-old stone ramparts, underground edifices, the Santa Lucia Barracks, Fort Santiago, and villages within the city walls all provided excellent cover from which to direct rifle fire at MacArthur’s men.

![]()

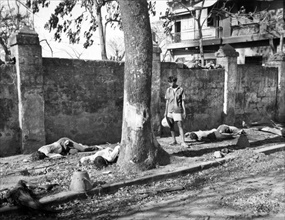

Right: A Filipino resident of Manila, confronted with the hellish sight of civilian corpses sprawled on a sidewalk, attempts to identify some of the victims. Earlier the fallen had been taken into “protective” custody by Iwabushi’s men and then killed as they tried to escape from the Ermita section of the city.

|  |

Left: Civilian survivors of the Battle for Manila, February 3 to March 3, 1945. During lulls in the fighting Japanese troops reputedly took out their anger and frustration on civilians caught in the crossfire. An estimated 100,000 civilians perished, most victims of ghastly Japanese atrocities, during the monthlong battle, but the true proportion of civilian deaths due to heavy American tank and artillery shellfire versus at the hands of Japanese troops remains uncertain.

![]()

Right: Refugees from war-torn districts of Manila, particularly the Intramuros enclave where heavy fighting took place, cross a pontoon bridge over the 150‑yard/137‑meter-wide Pasig River to safety. The fighting for Intramuros, where Iwabuchi’s men held around 4,000 civilian hostages, continued from February 23 to February 28. Having largely decimated Japanese forces by point-blank artillery and tank fire (air support was banned), GIs used close-combat flamethrowers, bazookas, Thompson submachine guns, Browning automatic rifles, grenades, and satchel charges to root out and exterminate Japanese defenders.

|  |

Left: Intramuros evacuees stream out of the walled city to the safety of American lines. Less than 3,000 civilians escaped the U.S. siege and assault of Intramuros, mostly women and children whom the Japanese released on February 23. Japanese naval personnel and soldiers killed 1,000 men and women, while the other hostages, including approximately 600 American POWs being held in the dungeons of colonial Fort Santiago, died during the American shelling.

![]()

Right: The bodies of Japanese troopers killed in the heavy fighting in Manila lie in a heap where they fell on February 22, 1945. On the main island of Luzon where Manila is located, Japanese soldiers and sailors suffered roughly 214,585 casualties, consisting of 9,050 captured and 205,535 dead.

Asian Stalingrad: U.S. Army’s Battle of Manila, February–March 1945

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click