AUSCHWITZ GAS CHAMBERS SHUT DOWN

Auschwitz-Birkenau, Occupied Poland • October 30, 1944

On this date in 1944 in Poland, the last murders by poison gas took place at the Nazis’ largest and arguably most infamous death camp, Auschwitz-Birkenau (Polish, Oświęcim), one of eight camps used for mass murder during World War II. (Six were in what is today Poland, one in Belarus, and one in Croatia, the latter operated by fascist Ustaše forces.) Established in 1940 under Germany’s Minister of the Interior Heinrich Himmler and expanded by camp commandant SS-Obersturmbannfuehrer (Lt. Col.) Rudolf Hoess (Höss, pronounced “hearst” without the “t”), Auschwitz-Birkenau was the site where an estimated 1.1 million people, around 90 percent of them Jews, were killed in gas chambers (located at Birkenau) or by clubs and hatchets, shootings, hangings (usually during roll call), disease (both natural [e.g., typhus] and medically inflicted), physical exhaustion, malnutrition, and starvation.

After Adolf Hitler had ordered the physical extermination of Europe’s Jews—das juedische “Parasitentum,” (English, Jewish parasitic population) as the Nazis referred to Jews—Himmler selected Hoess’s forced labor camp as a killing center owing to its easy access by rail, its proximity to mineral resources, and its relative isolation in the southwestern Polish area annexed by the Reich in October 1939, becoming a part of Germany’s Upper Silesia Province (Ostoberschlesien). Originally Auschwitz housed Soviet POWs, but it also processed those rounded up under Nacht und Nebel, the Nazis’ “disappearance” campaign. Prisoners whose files were marked “return not desired” or “do not transfer” were killed. Camp labor, estimated at over 400,000, was used extensively in quarries, ponds dredging mud and clearing rushes, and on-site factories established by Siemens, Krupp (munitions), and IG Farben (synthetic rubber).

During his superintendency, Hoess tested and perfected the techniques of mass killing that made Auschwitz the most potent symbol of the Holocaust and certainly the most efficiently murderous instrument of the “Final Solution.” During one 24‑hour period, Hoess calculated he had exterminated 10,000 people. Victims were driven into the gas chambers with their arms raised above their heads to accommodate more; in the ovens children were stacked one on top of the other several layers high for the same reason. When the camp was liberated by the Soviets on January 27, 1945, only about 7,600 prisoners were present, while roughly 50,000 had been hastily evacuated by the Nazis; many POWs died on the forced march from Auschwitz. Hoess, captured by British troops in 1946, was turned over to the Poles, who, after his trial in Warsaw, hanged him adjacent to one of Auschwitz’s crematoria on April 16, 1947. Hoess had just he finished writing his chilling memoir, Death Dealer, first published in German in 1956. A debate continues to rage over why the Allies did not act more swiftly to put Auschwitz-Birkenau and other Nazi death camps out of existence (see below).

![]()

Concentration-Death Camp Auschwitz-Birkenau, May 1940 to January 1945

|

Above: The Auschwitz-Birkenau complex as photographed on June 26, 1944, from an altitude of 30,000. The first aerial reconnaissance photographs of Auschwitz I (main camp) and Auschwitz II (Birkenau extermination camp with its gas chambers and crematoria) were taken on April 4, 1944, by a Photo Recon Squadron of the South African Air Force. The pilot flew out of Foggia, an Allied airfield in Southern Italy, originally to photograph the IG Farben war production factory at Monowitz (Auschwitz III) and other war production and military facilities in the area. The South African Photo Recon Squadron photographed the factory and parts of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp complex, including the crematoria, on May 31, June 26, August 25, and September 8, 1944. The May 31 photo material was shared with the U.S. Fifteenth Air Force, which struck the IG Farben factory on August 20 and September 13 and a military hospital on December 26, 1944. The 5th Photographic Reconnaissance Group of the Fifteenth Air Force, operating from Bari, Southern Italy, flew over the Auschwitz area on November 29, December 21, and finally on January 14, 1945—only two weeks before the liberation of the camp by the Soviet Army. A debate continues to this day over why Auschwitz-Birkenau or, at a minimum, the railroad tracks leading to the complex were not bombed by the Allies, who were alerted by camp escapees as early as 1942 to the industrial-scale murders and massive suffering taking place there. Troubling is that high-ranking military leaders never knew of the existence of the Auschwitz-Birkenau aerial reconnaissance photos. One argument against acting on the then evidence focuses on the technical difficulty, risk, and danger to the camp occupants inherent in even precision bombing Auschwitz-Birkenau. A U.S. bombing operation against a factory adjacent to the Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar, Germany, on August 24, 1944, was a disaster, killing 315 prisoners and wounding over 1,400. An attack on Auschwitz-Birkenau using a margin of error similar to that of the Buchenwald calamity might have cost 2,000–3,000 lives. Expressing sympathy for the idea of bombing Auschwitz, the air force stuck with bombing military targets even in the face of evidence that the Germans were increasing their extermination activities, especially against Hungarian Jews, when gas chambers and crematoria ran 24/7. Smashing rail lines between Hungary and Auschwitz for even one day could conceivably have saved 10,000 Hungarian Jews from death that day.

|  |

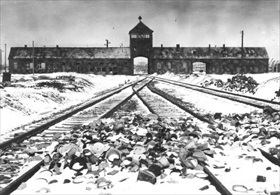

Left: Photo of Birkenau (the extermination camp at Auschwitz) following the camp’s liberation on January 27, 1945. In the foreground is the unloading ramp (the so-called Judenrampe) and in the distance Birkenau’s main gate called the “Gate of Death.”

![]()

Right: Beginning on January 27, 1945, almost 9,000 prisoners in Auschwitz I (the Stammlager, or main camp), Auschwitz II-Birkenau (the extermination camp), and Monowitz-Buna (Monowice, or Auschwitz III), judged unfit to join the SS forced evacuation march, were liberated by Soviet troops, a day commemorated around the world as International Holocaust Remembrance Day. Over 230 Soviet soldiers died while liberating the camps, subcamps, and the nearby city of Oświęcim. In 1947, Poland founded a museum on the site of Auschwitz I and II. Millions of visitors (2,320,000 in 2019) have passed through the iron entrance gate to Auschwitz crowned with the notorious sign ARBEIT MACHT FREI (“Work Sets You Free”). A cast made from the original sign can be seen at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. The Nazis placed the ARBEIT MACHT FREI slogan over or on a number of camp entrance gates, including gates at Sachsenhausen (north of Berlin), Dachau (north of Munich), and Theresienstadt (Czech Republic).

|  |

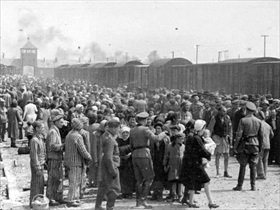

Left: Hungarian Jews on the Judenrampe (Jewish ramp) after disembarking from transport trains, May 1944. Being directed links! (to the left) meant the gas chambers at Birkenau. Sent rechts! (to the right)—as was the fate of between 20 and 40 percent of the arrivals—meant labor camp.

![]()

Right: Hungarian Jewish mothers, children, elderly, and infirm sent links (to the left) after “selection,” May 1944. They would be murdered in gas chambers soon thereafter.

|  |

Left: Survivors at the camp liberated by the Red Army in January 1945. Army medics and orderlies gave the first organized help to survivors. Two Soviet field hospitals soon arrived and began caring for more than 4,500 ex-prisoners from more than 20 countries, most of them Jews. Numerous Polish volunteers from Oświęcim and the vicinity, as well as other parts of the country, also arrived to help. Most of the volunteers belonged to the Polish Red Cross. Liberated prisoners who were in relatively good physical condition left Auschwitz immediately. Most of the patients in the hospital did the same within three to four months.

![]()

Right: Child survivors of Auschwitz, wearing adult-size prisoner jackets, stand behind a barbed wire fence on the day of their liberation by the Red Army. The majority of the liberated child prisoners left Auschwitz in separate groups in February and March 1945, with most of them going to charitable institutions or children’s homes. Only a few were ever reunited with their parents.

The Auschwitz Album, 1944, the Only Surviving Visual Evidence of the Process of Mass Murder at Auschwitz-Birkenau

![]()

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click

History buffs, there is good news! The Daily Chronicles of World War II is now available as an ebook for $4.99 on Amazon.com. Containing a year’s worth of dated entries from this website, the ebook brings the story of this tumultuous era to life in a compelling, authoritative, and succinct manner. Featuring inventive navigation aids, the ebook enables readers to instantly move forward or backward by month and date to different dated entries. Simple and elegant! Click